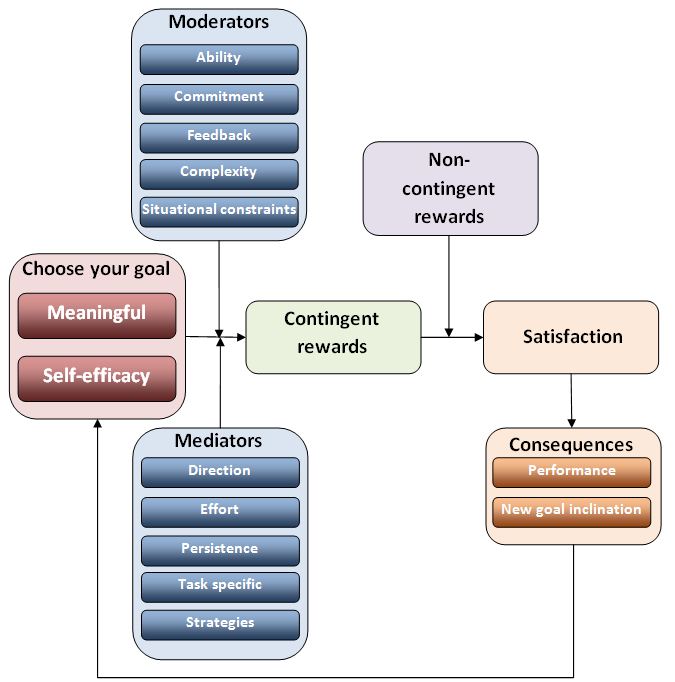

The anatomy of a New Year’s resolution: Goal setting psychology by Gary Latham and Edwin Locke

Between 40% to 50% of American adults make New Year’s resolutions. Of those, 77% will keep their commitment for one week, 55% for one month, 40% for six months, and only 19% for two years. A goal-setting model by academic gurus Latham and Locke can help you be on the positive side of those statistics.

Choose your goal

The first thing to consider is how you select which goals to choose. Research has shown your success at achieving your goal will increase if you have more of the following two factors:

- Meaningful: What does this goal mean to you?

The goal should have meaning to you, resulting in personal growth. The greater the growth, the more engaged you will be with realising the outcomes. - Self-efficacy: Do you feel you can achieve this goal?

The greater your self-efficacy, or your self confidence that the goal is attainable, the greater your chances of success. Build your belief that you can fulfil the goal through means such as remembering past success, acknowledgement of your abilities and potential, and/or affirmation from a support network.

Moderators and Mediators

Here are some factors that can facilitate or hinder your attempts at achieving your goal:

- Ability: Are you able to achieve this goal?

The more capable you are, the more likely you are to achieve your goal. Keep in mind ability can be developed through the process of goal attainment. You get better at it the more you try to achieve it. - Commitment: How committed are you to achieving this goal?

Commitment is expressed in thoughts, words, and actions and can be developed. There is some truth to the adage “fake it till you feel it” if it helps you achieve a worthwhile goal. - Feedback: Can you receive feedback on your progress towards your goal?

You will have more chance of success if there is positive reinforcement between initiation and realisation. This has proven to be one of the more contributing elements to goal success. - Complexity: Is the goal too complex or too simple?

The more straightforward the goal, the easier it is to attain. Complexity is related to the nature of the task itself and is introduced through attributes such as dependency on other goals and integration or conflict with other tasks. Keep in mind, however, that effort and performance can increase for complex, challenging goals. Dumb it down too much and you won’t grow. - Situational constraints: What are the barriers to achieving your goal?

While the goal can be challenging, try to remove the situational barriers as much as possible. If you are trying to work out, provide the time, space and money required. If you are losing weight, remove negative food and make positive food readily available. Make it easy to be a success. - Direction: Is the goal in line wth your overall direction?

The goal should be in-line with overall direction. If I have to go out of my way to achieve my goal, it is less likely to be realised. - Effort: Are you prepared to put in the effort required to achieve your goal?

Common sense dictates the more I apply myself, the more likely I will achieve my goal. Like commitment, effort is a conscious decision. - Persistence: Will you keep at it until the goal is realised, even when you fail?

Keep at it. The statistics of success over time are telling. The big challenge is continuing to apply yourself after you get back into your routine. If you fail, get back up. Failure and goal realisation are not exclusive, and are often complementary. - Task specific: Is the goal defined enough?

Specificity is critical. “Do your best” or “do better” goals are much more prone to failure than “Accomplish X task by Y amount before Z time”. “Lose weight” or “work out more” are less likely to succeed than “lose 10 pounds by June”. - Strategies: Have you planned out how you will achieve your goal?

The more you invest in planning how you will achieve your goal, the more likely you will succeed, as compared tho those who leave it to chance.

Rewards

Two types of rewards to consider are contingent and non-contingent rewards:

- Contingent rewards: Are there ways you can reward yourself for prorgess towards your goal?

Contingent rewards are in-line with goal success. If there is no form of personal return from your effort, you are unlikely to realise your goal. These rewards can be internal from yourself and external from others. They should also be iterative, received at milestones along the way to final goal attainment. - Non-contingent rewards: Can you make the overall process rewarding?

Not as critical, non-contingent rewards are positive reinforcements not associated with the goal path but still supporting the outcome.

Outcomes

The model above is a straight-forward formula proven by mountains of research.

- If the factors are present, you will achieve your goal.

- If you achieve your goal, you will have satisfaction.

- If you have satisfaction, you will be more likely to improve your overall life performance and be more inclined to set new goals, thus starting the process over again for more challenging and more rewarding goals.

The model above can act as a situational check list to assess how likely a goal is to be achieved as well as for reflection to assess why goals have not been achieved. Goals are achieved when they have meaning and you believe you can do it, when you have appropriate mediators and moderators in place, and when the reward structures and feedback loops are sufficient. The model takes away the excuses, highlighting that the emphasis on realising goals rests on the one who makes them.

I look forward to hearing of your success as you achieve your goals in the New Year!

1 thought on “The anatomy of a New Year’s resolution: Goal setting psychology by Gary Latham and Edwin Locke”

Comments are closed.