Accountability – research and perspectives: On blame, reputation, and counterfactuals

What does it mean to be accountable in business? Does it have to be enforced with the blame stick, or is there a better way through empowerment? You should know the answer if you are a leader or manager.

The need for accountability

The commercial sector does not appear to talk about accountability. If you search Google for “accountability”, over two-thirds of the first fifty results will be related to education or government and the remaining are informational or consulting services. Yet my previous post about the seventy percent failure rates in business would seem to indicate some form of accountability is necessary.

Dunn and Halsall use marketing as an example, noting some concerning statistics about the US 2009 marketing spend of $322 billion:

- 45% of marketing achieves positive ROI

- 37% of TV advertising is successful

- 16 to 35% of promotional spending results in positive returns

- 53% of senior marketers consider television advertising an effective activity for long term brand building

- 18% of senior marketers can tell if they are getting ROI from their spending.

Those are low percentages for people playing with such large sums of money. Yet the statistics could be excusable based on everyone doing the same thing and acknowledgement of the unknowns of the situation. The issue with excusing a lack of accountability in one commercial area is that it allows us to be unaccountable in other areas, such as what we saw with the banking sector during the GFC. If I am not accountable, how can I hold others accountable?

Greater accountability is needed, but what does the word really mean?

The good and bad of accountability

Organisational research shows that accountability can be good and bad. From the positive perspective, accountability is related to:

- Attentiveness

- job involvement, job competency, and citizenship behaviour

- job satisfaction, and

- performance

Unfortunately, there is a dark side to accountability as well. Negative aspects related to accountability include:

- inappropriate commitment to faulty courses of action, even when faulty logic has been exposed,

- lack of flexibility,

- poor cooperation, provision of inaccurate information, and a greater propensity to use threats and dominating behaviour in negotiations, and

- politically-motivated behaviour.

So which is it? How can research prove two sides of the same thing? The answer is found in the culture you create in your organisation.

The accountability paradox: empowerment, blame and personal reputation

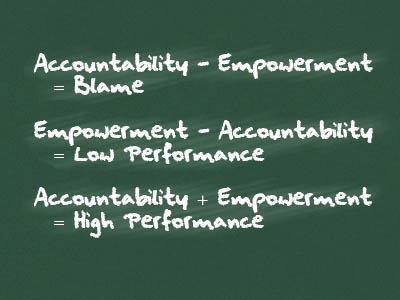

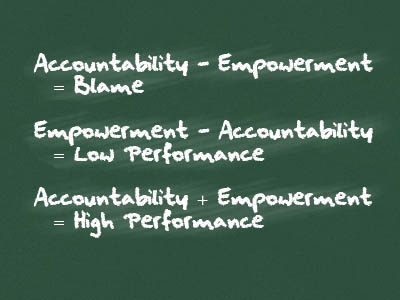

Accountability without a culture of empowerment results in blame. Some things we know about blame include:

- Blame shifts responsibility and identifies the fault as another person.

- Blame generates fear, destroys trust, makes data gathering difficult, and shifts the burden away from seeking truth.

- Blame drives underground those with the knowledge of what went wrong.

- Blame is based on the irrational assumption of erratic individuals operating in an otherwise safe system.

On the flip side, empowerment without accountability results in low performance. Take for example the poor response effort of the Hurricane Katrina disaster and consider the extent that empowerment requires autonomy. A post-mortem on the recovery effort found a significant failing was due to multiple autonomous organisations not being accountable. Empowerment and accountability need to go hand in hand if you are to achieve high performance.

Another issue with driving accountability without empowerment is found in the relationship between accountability and personal reputation. Increasing personal accountability while attacking the personal reputation of the one being held accountable results in lower performance, job tension and work-related depression. Forcing accountability through degrading the other party proves to be a self-fulfilling prophesy of the other party being unaccountable. The result is an “accountability paradox”, where enhanced accountability impedes performance.

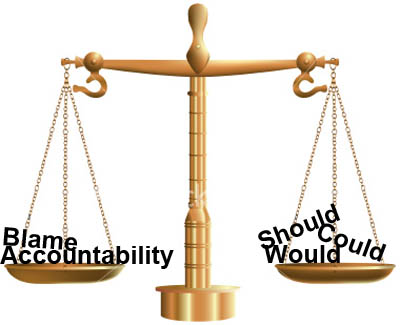

Considering the counterfactuals of could, would, should

Accountability is a property of both the person and the situation, both of which are assessed for competence when determining responsibility. To allocate blame means to hold the situation blameless, that the perpetrator could, would, and should have known. The practice of projecting what the other party could, would, and should have done is known as counterfactual thinking.

In an accountability situation, counterfactuals are assessed for three aspects: 1) harm or negative consequences, 2) consequences attributable to the discretionary action of the person, and 3) a violation of acceptable standard of behaviour. This assessment considers two situations: A) sins of commission (taking action) and the presence of knowledge; and B) sins of omission (not taking action) and ignorance.

Our sense of injustice and offense increases based on an increase in the perceived harm or violation. We are also more offended in situations involving commission and knowledge and less offended in situations of omission and ignorance.

This is why you see behaviour of passing the buck and dodging responsibility. Someone who consistently says “I do not understand how this could be” is actually saying “I am not accountable for this”. We have an inbuilt awareness that feigning ignorance will minimise the extent that we will be held accountable for what we “should have known”.

Understandable, but not acceptable

In the complexity of our commercial environments, it is entirely understandable that phone calls are missed, project deadline’s slip, and delivery of client content or assets are delayed. As soon as missed deadlines become acceptable by one party, then it becomes impossible for there to be reciprocal accountability. Just because it is understandable does not make it acceptable.

The way that accountability is applied determines overall team success. If you assume your system is perfect and you cultivate a culture of blame, then you will get the undesirable results outlined above. If you apply a balance of accountability and team empowerment, then you will succeed.

My thoughts on accountability are based on an awareness of my own need to be more accountable as my studio climbs past the 55 member head-count. As so often happens when you focus on an area, my own intent highlighted the lack of accountability and pervasiveness of blame in the wider market. I do not have control over the market, only myself, demonstrating that accountability starts with the individual.

The market reflects a need for accountability, and research guides us on the appropriate means for it to be applied through empowerment. With this information so readily at hand, it is difficult to excuse myself or business in general from what could, would, or should be known.

Another aspect to explore is that of accountability by the delegator.

When a person “fails”, that person represents only half, at most, of the accountablolity matrix. The employer has a responsibility to support employees, and if they fail, the employer might be the one who should be held accountable – was sufficient training provided? Resources? Similarly in education, the student is accountable, but the teacher plays a role too.

The way this is often addressed is to again transfer responsibility to the weaker party, “if you don’t have enough resources or training, you need to get them”, but that’s a cynical blame-shifting exercise.

Parr of the solution is to see every delegation of responsibilty as a relationship, a partnership. This has to mean shared accountability for results. Defining the accountablilities more and more precisely leads to blame. Sharing accountability leads to cooperative behaviour.

Those doing the delegating must be held accountable for the manner in which they delegate. If it shifts the locus of accountability, that’s abdication. Delegation is an expansion of the locus of accountability.