Did you inherit your career? Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription and compromise

I grew up in a family business. From age six to fourteen, my weekends were spent at first sweeping floors and then assisting in the manufacture of printed circuit boards. I returned nine years later as an Environmental Compliance manager following high school in Canada and a five-year stint in the U.S. Navy. As a then 23-year old, I recall a very distinct feeling of “Why me?”

Why should I be the one to be in this position? From a relative perspective, why are others around me in their positions compared to my own role? Am I here solely due to my position as the owner’s son? Do I have some genetically embedded propensity for electronics manufacturing that secures for me this role? Or am I the right person for the job?

Close to two decades on, I hear these same sentiments from those around me. I often hear the narrative that “I fell into it” or the more despondent “I never chose this”. Some even convey jealousy for others who they perceive as being content without needing career options. Even for those who say their career was planned, there are questions about what “might have been” given a different configuration of circumstances and choices.

Gottfredson’s theory

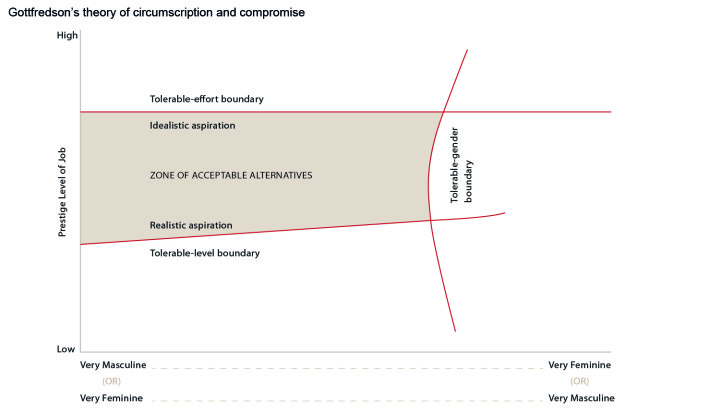

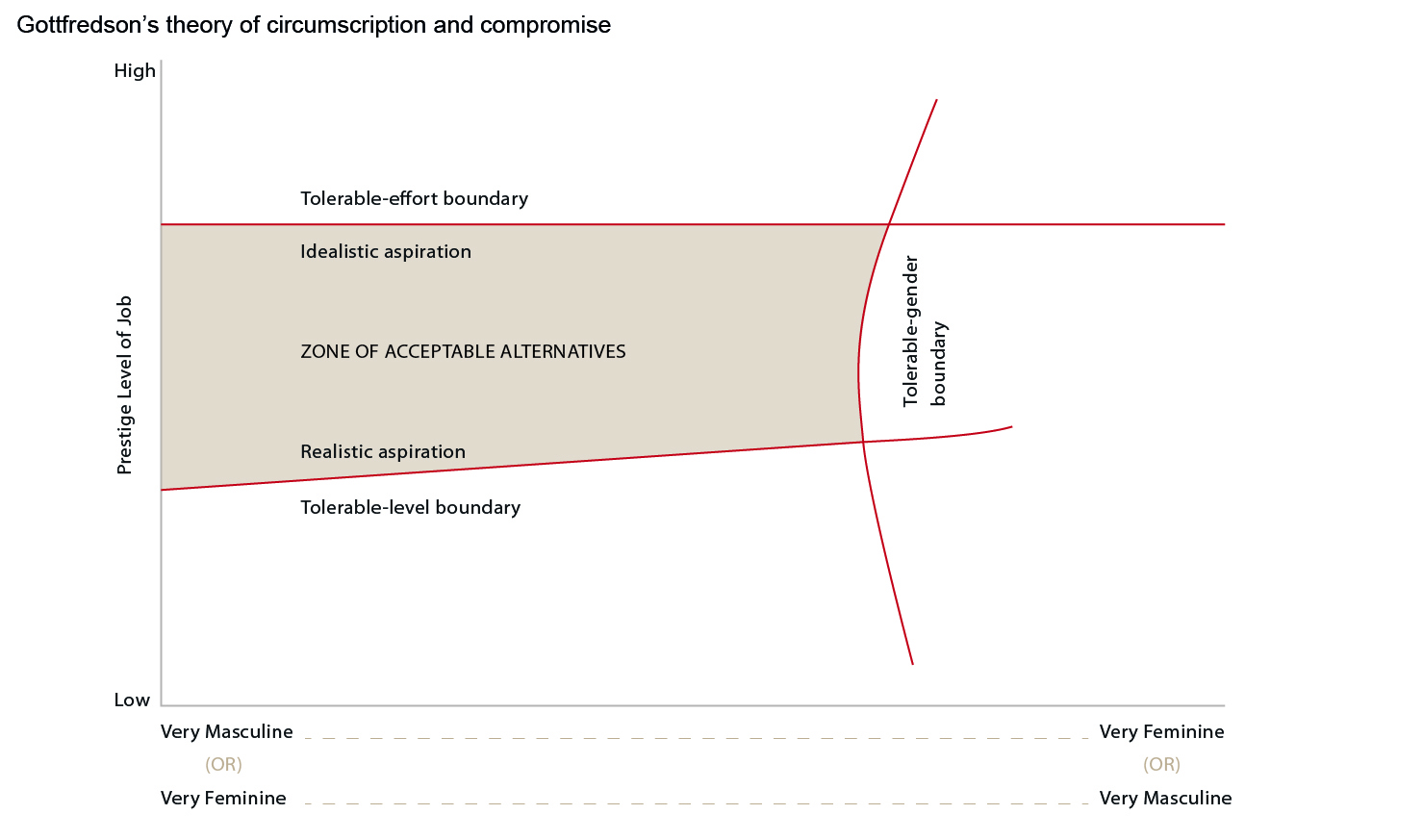

Linda Gottfredson shares a rational for our career directions in her theory of circumscription and compromise. In her theory, Gottfredson seeks to answer “Where do interests, abilities, and other determinants of vocational choice come from?” Essentially, why do we choose to do what we do?

The proposed answer lies in first understanding how we develop our self-concept. We then consider how we eliminate occupational alternatives that conflict with this self-concept through a process called circumscription. Finally, we look at the remaining options and compromise based on the certain criteria.

1. Defining our self-concept

We are complex creatures, made up of personalities, strengths, interests, skills, talents, and beliefs. This identity is defined by our genetic make-up, our environment and surrounding culture and relationships, and our experiences. But to what extent are we truly in control of defining who we are?

Gottfredson cites research that indicates our self-concept is culturally contingent and experience dependent. On the one hand, our interests, attitudes, and particular skills are strongly influenced by shared environments. On the other hand, we remain active agents of our own creation within the constraints of our genetic inheritance.

Our genetic compass urges, not commands, us in some directions rather than others. Our genetic inclination competes with culture, operating like a gyroscope guiding us towards one path over another. Our path is constrained by choices available in our culture and past choices we have made. For example, nothing in my genetic make-up or cultural environment would lead me to be a reggae singer and my past career choices preclude me from an easy transition into engineering.

This is not to say we are powerless to our genetic make-up and cultural influences. We become who we are through experience, and come to know ourselves through engaging with the world. Through these experiences, we find ways to reflect, reinforce, and better resonate with our personal tendencies.

You often hear of people who begin to redefine who they are one small experience at a time, creating a new self-image that is the sum of these new experiences. These redefining moments can come at different stages in our lives as our genetic makeup changes as we age.

In the classic debate of nature versus nurture, nature trumps in defining our self-concept. Socialisation theory, which proposes we are defined largely by our environment, has proven to be false. The older we get, the more our self-concept aligns with our genetic pre-disposition. We also become more familiar with who we are and adapt at working within our environment to suit who we are.

2. The process of circumscription

Our genetics, environment and experiences frame a circumscription (limiting or restriction) process where we eliminate occupational alternatives that conflict with our self-concept.

I considered this in my recent research into gender inequality. One of the contributing factors in the gender inequality debate is the fact that 60% of primary carers in Australia are female and over half of women with children under the age of two are not employed in the workforce. Another factor is that all but two of the top nine industries by earning potential are male-dominated.

When I raise these statistics to my female friends, a response I get back is “Yes, but what if I want to stay home with the children?” or “I want to work in my female-dominated industry”. I do not disagree with their preference, but ask why do you want it? Is it really your choice, or is it what you have chosen based on cultural influences?

These influences start early. Gottfredson proposes four stages of circumscription:

- Stage 1: Orientation to size and power (age 3 to 5)

Early on, we classify things as strong and weak, adult and child, big and small. We are taught to assign value judgments to these classifications and understand where we are placed within those judgments. We know our place as a child who is weak, and that we should desire to be an adult who is strong. - Stage 2: Orientation to sex roles (age 6 to 8)

We make distinctions based on broad gender categories and learn to assign activities and roles to those categories. We begin to understand where our genetically conditioned self-image is positioned within these culturally-defined categories. Boys and girls learn about what are acceptable boy and girl roles, in spite of or aligned with their natural inclinations. - Stage 3: Orientation to Social Valuation (age 9 to 13)

We begin to conceptualise jobs as abstract collections of activities, assign a social value to those jobs, and position ourselves within that value. We comprehend income, status, and effort and adjust our aspirations accordingly. - Stage 4: Orientation to Internal, Unique self (age 14+)

While we have previously eliminated unacceptable alternatives, we now seek roles that are compatible with our personal, psychological selves. We replace idealistic aspirations with realistic aspirations based on what we perceive are accessible options aligned with who we believe ourselves to be.

3. The act of compromise

While the four stages of circumscription are processes by which we eliminate occupations we deem unacceptable, compromise is the process by which we relinquish our most preferred alternatives for less compatible but more accessible ones. Within the roles we have short-listed based on perceived effort, prestige and gender, we select those positions within our social space based on what is available. We then define what is “good enough” and what is not “good enough”.

If our desired role is not available, we compromise on prestige rather than adjusting across gender roles. Someone who wants to be in engineering may opt for construction rather than taking a role as a hair dresser. Conversely, someone who wants to be a social worker may become an admin assistant rather than take a role in the mining industry.

Practical application

So what options does that leave us? Most western cultures promote a free economy where anyone can be or achieve anything. This makes for great movies, but is proven to be little more than idealism in most cases. In his book Understanding Careers, Kerr Inkson refers to the notion of careers as inheritance to outline factors that predetermine our perceived occupational choice.

Structures that are proven to predict our career options include social class, social mobility, education, race, gender, and family. It is my research into these aspects of career inheritance that prompted me to post about how the technology industry is breaking down some of these barriers.

Knowledge is power, particularly knowledge about why we do what we do and the unseen influences on our beliefs and behaviour. Gottfredson’s theory outlined in the diagram above helps us understand our upper limit of effort we apply, and the lower limit on how low we will stoop for a low prestige position. It also helps us frame how our predisposition towards gender roles guides us towards one job over another.

Rather than being fatalistic, this information can be empowering. Yes, we all have inherited constraints, but this also presents opportunities for us to excel within, in spite of, and even challenge these boundaries . Gottfredson states that “our environment is both cause and effect – people shape the environments that shape them”.

I will close with Gottfredson’s five recommendations for those who explore career transitions:

- Work with your core traits

You have a genetic predisposition you are unlikely to change. Acknowledge your strengths and pursue roles that take advantage of those strengths. - Sample a broad range of experiences

Our life is the sum of our experiences. If you feel stuck, try other things. Volunteer, try a hobby, request informational interviews from those in other careers, or engage in networking events such as Meetups in areas of potential interest. There are few who will turn away someone who expresses in interest in something they are passionate about. - Surround yourself with people, activities, and settings that bring out the best in you

What you focus on, you create. Like attracts like. Surround yourself with that which will support you in being the person you want to be. - Acknowledge that each person and situation is unique

Be careful about comparing yourself to others. It is your own journey. - Keep an open mind about your options

Be aware of your limits, but do not let them limit you. If something seems to be too much effort, ask yourself what you have to lose. If something seems beneath you, ask yourself if pride is getting in the way.

I hope this helped you better understand why it is you do what you do, and what you can do about pursuing that which you want to do more. If what you want to do involves responding to blog posts, feel free to start sampling such an experience through the options below.

great to know I was doing those 5 things before you wrote the blog 😉