Blog posts from 1932: Finding wisdom in Essays by Modern Masters

Collections of old books remind me of the consistency of life. The tattered spines whisper that wisdom is constant and not dependent on a refresh of my LinkedIn news feed. The writers take me aside and whisper that whatever I have to say has likely been said before, and yet the world still graciously and patiently waits in anticipation for me to say what is on my mind.

The layer of dust on the books makes me feel all the more like an explorer, uncovering truths hidden in plain sight. Such bookshelves can be found tucked away in antique shops, in the back corner of second-hand bookstores, and in the houses of grandparents around the world.

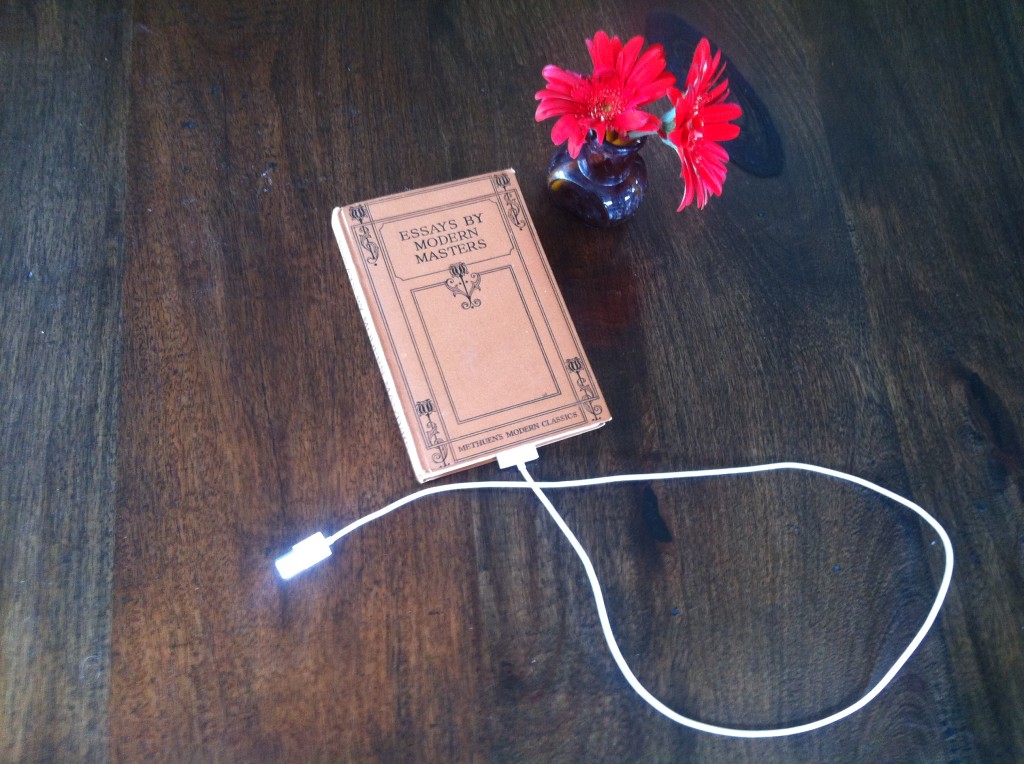

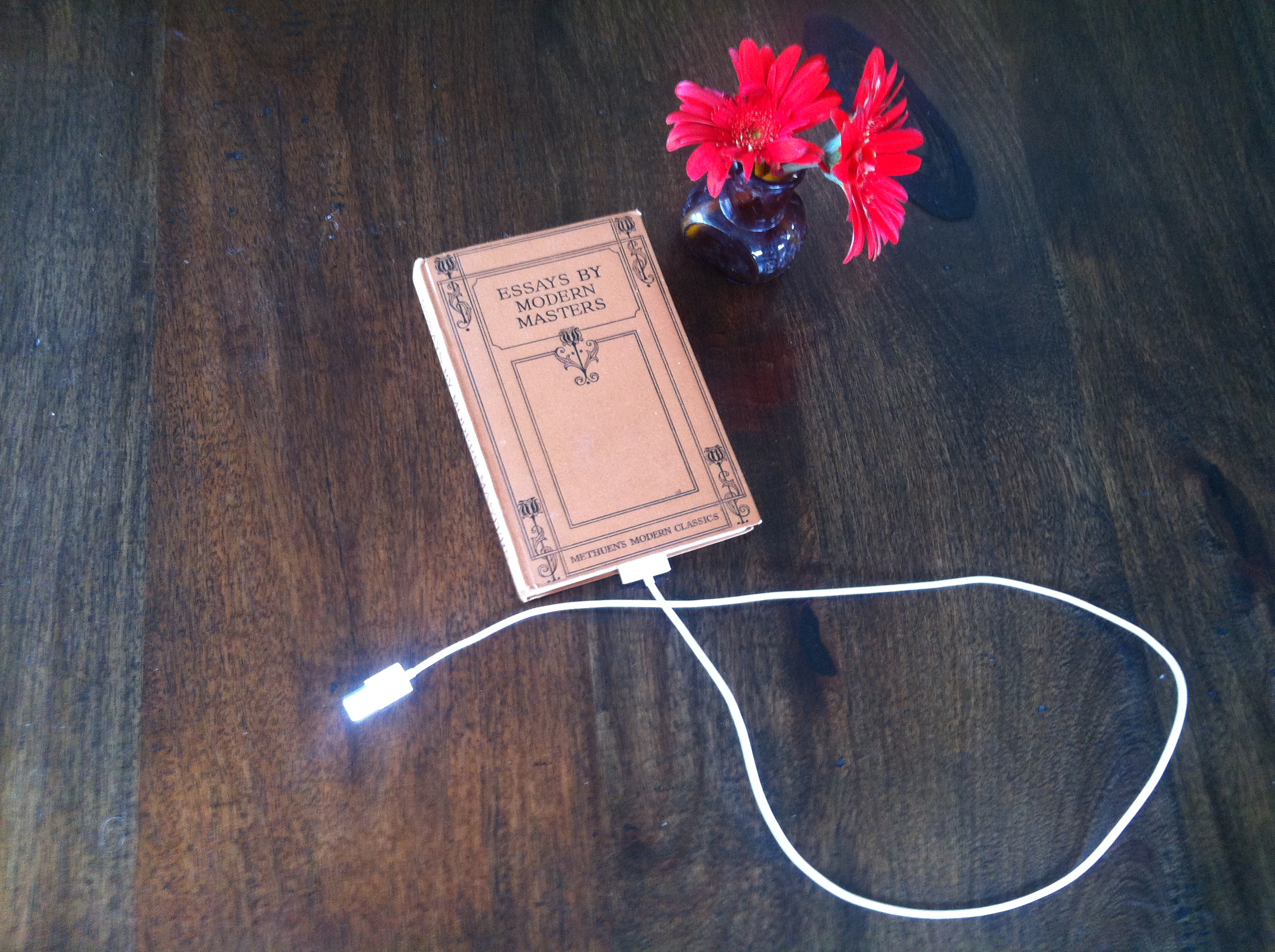

I was in the latter category of structure during a visit to my wife’s family in Bendigo when one unassuming book stood out by nature of its title: Essays by Modern Masters. The title at first seemed to me ironic given the fifth edition in my hand was published in 1932.

Reading through the work corrected my assessment for all three aspects of the title: The essays were akin to what we would now consider to be on the longer side of a blog post. The work was as relevant as any of the modern material I see on the Internet today. Finally, the contributors were masters of communicating in a way that is overlooked in our ease of contemporary content publishing.

Modern thoughts by modern masters

I wonder what these modern masters would think of our current media consumption practices. We exist on a steady diet of pithy quotes overlayed on pictures of sunsets, holy writings and foundational speeches condensed to a single quote to satisfy our daily dose of inspiration, and paragraphs replaced with internet memes and video.

When I compare my diet of online articles against the collection of four page narratives in the book, I feel what one might experience sitting down to a home cooked meal after weeks of consuming fast food. It is not until you taste the depth of substance that you realise what you have been missing.

The authors wrote to a world that was not subjected to our over-exposure of media, where competition for reader’s attention was with other books in the library rather than a persistent nagging call of electronics and an “always-on” professional life. Our thoughts are no longer left to their own devices, but rather we force our thoughts onto hand-held devices as soon as we open our eyes.

I am not, however, making the mistake of assuming the authors of almost a century ago are any different form of humanity. I believe G. K. Chesterton was foreshadowing a form of augmented reality in his thoughts On Lying in Bed:

Lying in bed would be an altogether perfect and supreme experience if only one had a coloured pencil long enough to draw on the ceiling. This, however, is not generally a part of the domestic apparatus on the premises. I think myself that the thing might be managed with several pails of Aspinall and a broom. Only if one worked in a really sweeping and masterly way, and laid on the colour in great washes, it might drip down again on one’s face in floods of rich and mingled colour like some strange fairy rain; and that would have its disadvantages. I am afraid it would be necessary to stick to black and white in this form of artistic composition. To that purpose, indeed, the white ceiling would be of the greatest possible use; in fact, it is the only use I think of a white ceiling being put to.

Just like us

These writers from over a century ago shared experiences we can relate to in our current times. Robert Lynd in The Shy Fathers shares a fear common to many fathers who subject the world to the “dad joke”:

There is, I am told, no greater happiness known on earth than that of a father who, after a party to which his children’s school friends have been invited, can lie back in his chair and tell himself that he did not behave so badly after all. It is always pleasant to pass an examination, but there is no examination which it is a more blessed relief to pass than an examination by one’s children’s friends. Fathers have told me of the nervousness they have seen in their children on such occasions – of the impatient expression they have observed on the little face that, at a joke that has no point that nobody is able to see, tells them of the silent soliloquy: “Daddy being silly again!” Pity the tremors of children for their fathers. Pity the tremors of fathers for themselves. Happy is the child whose father acquits himself with credit in the presence of its friends. How delightful it was in one’s childhood to see one’s own father being a success in such trying circumstances.

Worse than the dad joke is the chronic case of the man flu, which Lynd proves is not a contemporary condition in his post On Being Rather Ill:

I am not one of those moral giants who can enjoy a bad conscience and a bad toothache at the same time. I am not sure, indeed, that illness does not entirely unfit me for higher life. I become self-centred, impatient, incapable of even a moderately noble thought. There are invalids who, when they are in pain, try to hide the fact from other people. I, on the contrary, like other people to know about my sufferings. I am even, I suspect, inclined to exaggerate them. If a friend calls, I at once tell him where the pain is, what the doctor said, and the still worse things I discovered in the medical dictionary.

A search for wisdom

I felt an affinity to these authors, not by any stretch in the form of quality of writing, but in perspective and thought process. I consider my struggles with clearly articulating what I see around me, but still using what is around me to articulate what I see. Chesterton shares a similar sentiment in his ponderings about A Piece of Chalk:

But though I could not with a crayon get the best out of the landscape, it does not follow that the landscape was not getting the best out of me.

Chesterton did not have rows of self-help books and thousands of leadership blog posts to draw from. Yet I propose that his metaphoric exposition comparing the value of virtues to a white piece of chalk inspires one to greatness as much as the current plethora of blog posts about three steps to greatness or one thing to remember:

Virtue is not the absence of vices or the avoidance of moral dangers; virtue is a vivid and separate thing, like pain or a particular smell. Mercy does not mean not being cruel or sparing people revenge or punishment; it means a plain and positive thing like the sun, which one has either seen or not seen. Chastity does not mean abstention from sexual wrong; it means something flaming, like Joan of Arc. In a word, God paints in many colours; but he never paints so gorgeously, I had almost said so gaudily, as when he paints in white.

I read statements such as this and am reminded that leadership is an active intent, not simply the lack of following. We build upon volumes of research on happiness and motivation, which all seem to reiterate the wisdom of the past.

Case in point, self-help books abound on the benefits of gratitude. Chesterton pre-dates this research in his reflection on having a sprained ankle in The Advantages of Having One Leg:

The way to love anything is to realise that it might be lost. In one of my feet I can feel how strong and splendid a foot is; in the other I can realise how very much otherwise it might have been. The moral of the thing is wholly exhilarating. This world and all our powers in it are far more awful and beautiful than we ever know until some accident reminds us. If you wish to perceive that limitless felicity, limit yourself if only for a moment.

This concept of perspective is shared by Lynd when he uses food to explore whether our desire is for a thing or for the idea of a thing in his piece The Idea:

How seldom does a coffee equal the idea of a coffee! Who does not love coffee as an idea? Who is not continually disappointed by coffee as a fact? If most of us go on drinking coffee, it is because we live in the perpetual pursuit of an idea, not because we have much hope that the next cup of coffee is going to be a good one. We know from experience that there is much difference between the coffee we drink in restaurants and the coffee we drink in our imaginations as there is between war-time beer and nectar. But such idealists are mortals that we go on drinking it in restaurants, on railway trains, and even in lodgings. We should lose heart, perhaps, and take to milder liquors if it were not that every now and then we do get a cup of coffee in which the idea of coffee seems almost to have been realised on earth.

Lynd describes a condition of the optimist I frequently debate with myself. If I find myself satisfied in all things, can I not enjoy my satisfaction regardless of the actual quality of the thing? I would prefer to be in the group Lynd describes: “If they are told that the coffee at such and such restaurant is always good, it will always be good to them.”

This is a condition we seem to lose somewhere along the way as society demands dissatisfaction. Lynd notes:

As children we ate, not cakes, but ideas; now we eat, not ideas, but cakes. We sought perfection but found only commonness. Gods and men, we are all deluded thus. Go over all the things you would like to eat and drink, and you will find that, in most cases, what you would like to eat or drink is not the thing in itself but the idea of the thing.

I believe the opportunity here is to bring to awareness the idea of the thing and fully embrace the idea as we make it our reality. A. A. Milne is yet another of the masters who convey this approach in his work titled Superstition:

I do not mean that I believe that a horseshoe hung up in the house will bring me good luck; I mean that if anybody does believe this, then the hanging up of his horseshoe will probably bring him good luck. For if you believe you are going to be lucky, you go about your business with a smile, you take disaster with a smile, you start afresh with a smile. And to do that is to be in the way of happiness.

Applying wisdom

There is a propensity in our “modern” age to dismiss anything older than the current age as irrelevant. I argue that the words of those in the past were written by people just like us with perspectives as relevant today as they were then.

These modern masters wrote about their search for love, truth and happiness, not dissimilar to sentiments many contemporary writers post in the online space. We have become more efficient and prolific in our writing, but have we become any more proficient in applying this wisdom?

I see parallels in concepts such as innovation, where it is not the idea but the execution that defines what is innovative. I recently wrote about the concept of happiness, where it is not external pleasure but internal discipline that defines our state of mind. So it appears to be similar with wisdom.

Wisdom is found not in the writings of others but in the application of those writings. Words in a book collect dust just as pixels on a screen take up bandwidth. Words can only be considered wisdom if I view them with fresh eyes and critically apply the words to my life.

What masters are you following, be they modern or not so much? And how have you been able to apply their wisdom in your life? If you are so inclined, please feel free to share below so the rest of us may benefit.

Image credits: http://flic.kr/p/2DgLk, http://flic.kr/p/8n74zU

1 thought on “Blog posts from 1932: Finding wisdom in Essays by Modern Masters”

Comments are closed.