Our happiness model explained, courtesy of Mikhail Csikszentmihaly

After decades of research, we know what makes us happy. Research has found a few basic life hacks that have proven to improve the quality of our lives. We track happiness over time, such as the case with the Harvard study of 268 men over 72 years that shows that education, stable marriage, not smoking, not abusing alcohol, exercise, and healthy weight all predict healthy aging, both physically and psychologically. Places like the Australian Centre on Quality of Life at Deakin University produce reports that show how our subjective wellbeing is impacted by factors such as household income, gender, age, household composition, marital status, work status, and life events.

Reading through this research gives the impression that if we do certain things or configure our life in a certain way, then we will be happy. We then have what amounts to a medical prescription for the person looking for happiness. If married people are happier, then I should be married. If rich people are happier, then I should be rich. If women are happier, then I should become… um, wait.

And therein lies a problem. I rest uncomfortably with the notion that happiness is dependent upon my lot in life. A person can take action on aspects of their life such as weight and smoking. A poor single male wishing he was rich or married, however, can feel as helpless about changing his situation as though he were wishing he was female. And often if he fulfils the prescription, the remedy does not work and he can still search for happiness.

Should happiness elude those who do not fit a certain configuration of life? The question I see it is not “What do I do to be happy in the future?” but “What is the process by which I can be happy in my current situation?” Is there a way that people can choose to be happy across cultures and life situations?

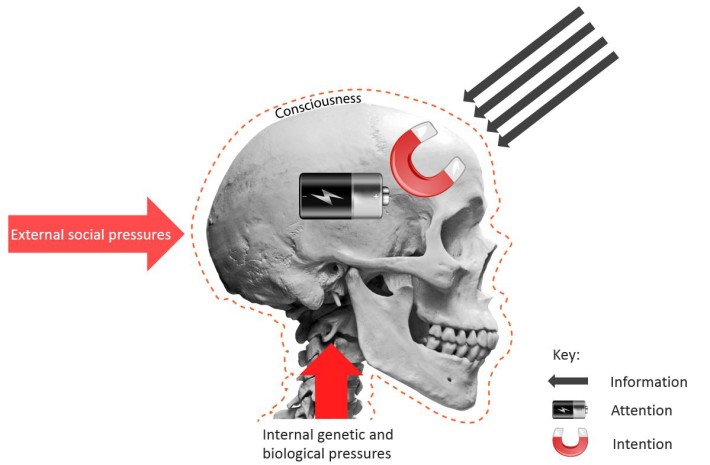

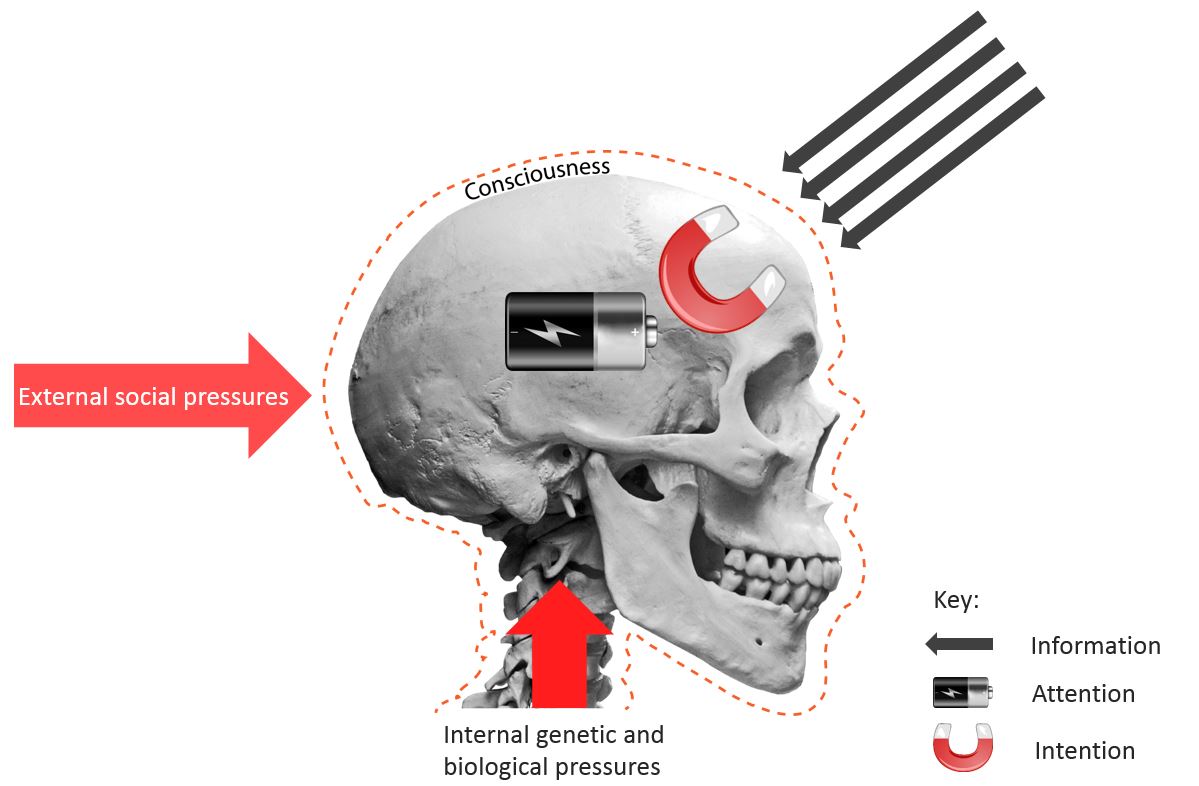

Mihaly Csikszentmihaly proposes that there is a way as he breaks down the anatomy of our consciousness in his book Flow.

The model of happiness

It turns out there is a model of happiness available to most of us. Mihaly shares his observations of thousands of people and decades of research in his outline of the different pieces that form a model of how we can achieve what he refers to as optimal experience, or flow.

The basic premise of the model goes something like this:

- We become aware of and control our response to our internal and external pressures.

- We intentionally determine what information enters our consciousness.

- Our intentions are driven and directed by our attention.

- Those who are able to better direct and be in control of their intentions and manage their response to information as it enters their consciousness have improved quality of life.

This is the somewhat scientific explanation for business articles you might see with titles such as Mindfulness: When Focus Means Single-Tasking and Why Focus Should Really Be the Next “Big Thing”.

Internal and external pressures

The first thing to acknowledge is that we are all influenced by internal genetic and biological pressures and external pressures from the society in which we live. Our internal pressures include our needs for sex, food, survival, and community that we are born with and that are developed through learned behaviour over the course of our lives.

We are not always successful in controlling these urges, however. We create for ourselves systems to help us both control and satisfy our urges in socially acceptable ways. We have things like governments, religions, social causes, media, and commercial corporations to inform us in which ways we should think and behave.

Yet while these pressures help us co-exist, we become vulnerable when we completely give in to either internal or external pressures. Our internal search for pleasure is designed for “the preservation of our species, not for our own personal advantage.” The external pressures we experience are designed to keep us in check and to “desire rewards that others agreed we should long for.”

“When we follow the suggestions of genetic and social instructions without question we relinquish control of consciousness and become helpless playthings of impersonal forces.”

Information

In addition to what we receive from internal and external pressures and controls, life presents us with a seemingly infinite amount of information. Mihaly refers to research that says we can process about 126 bits per second. For reference, a single conversation uses about 40 bits of information per second. This means we can have at most three conversations at once and still somewhat understand what is happening.

This is perhaps why people have a need to whip out their smart phone and check emails in the middle of a single conversation or allow our mind to wander to what else is on our plate for the day. We have a desperate need to fill up our capacity for information. We selectively reduce the amount of information we feel we need from the conversation at hand. We fill up the rest of our information-gathering capacity with other thoughts and actions in the spirit of multi-tasking.

What this does is stop us from being in the moment. We can miss non-verbal cues that help us make a deep connection with the other person. We may neglect to note our own response to the conversation such as anxiety levels or a trigger on some new thought. Finally, we can miss the opportunity to fully participate in the conversation and respond in a way that adds value to everyone involved.

“The information we allow into consciousness becomes extremely important; it is, in fact, what determines the content and quality of life.”

Consciousness

Information that manages to make it through enters what we refer to as our consciousness. Our consciousness satisfies two very important functions. The first is it deliberately weighs what our senses tell us and responds accordingly. The second function is it fills in gaps and provides imagination to invent information that did not exist before.

It is important to note that information has no value until it enters our consciousness. Once information enters our consciousness, we assign to it a value such as “good” or “bad”, “like” or “dislike”.

Our consciousness is ours. We own it and theoretically we control it. A car cuts us off as we drive and we determine whether we calmly acknowledge they may have made a mistake or we are filled with rage. We experience disruption in our employment and we decide whether we look at it as an opportunity or a tragedy. It is the mastery of our consciousness that can determine the quality of our lives.

“A person can make himself or herself happy or miserable regardless of what is actually happening ‘outside’ just by changing the contents of consciousness. This ability to persevere despite obstacles and setbacks is the quality people most admire in others and justly so; it is probably the most important trait not only for succeeding in life, but enjoying it as well.”

Intention

Intentions are what bring order to the information we get from the outside world and the internal and external pressures that enter into our consciousness. Intentions are described as a magnet that keeps our mind focused in one area or another.

Intentions are what order information into a hierarchy of goals. It is our intention that we binge on Doritos or say no to our body crying out for a Big Mac, that we go to bed early or stay up and study for the exam.

Our intentions are automatic inclinations, driven by beliefs and predictors of our behaviour. We are all aware, however, that we do not always behave as we intend.

“Intention does not say why a person wants to do certain things, but simply states that he or she does.”

Attention

If intention is like a magnet, then attention can be seen as the motor that points the magnet towards certain information. With attention, we can focus our intent towards information and internal and external cues that bring joy or distress.

Attention is an energy, in that it can be consumed and replenished. When the energy is low or attention is focused on areas that hold little interest to our goals, we can have “short-attention span” or easily “lose attention”. However, when the information is something that is of interest and aligned with our goals, then it is said to “hold our attention.”

“The mark of a person who is in control of consciousness is the ability to focus attention at will, to be oblivious to distractions, to concentrate for as long as it takes to achieve a goal, and not longer. The person who can do this usually enjoys the normal course of everyday life… [Attention] is an energy under our control, to do with as we please; hence, attention is our most important tool in the task of improving experience.”

Self

Our self is the sum of everything that enters our consciousness. Our self is defined as we use attention to selectively bring information into consciousness and order it into a series of goals. We become aware of our self through the expression of these goals.

This process is both accidental and intentional. We may get exposed unintentionally to an activity, such as scuba diving or classical music. A positive experience may then prompt us to focus our intentions to repeating the experience and re-define aspects of our self. In a seemingly circular reference, our attention defines our self, and our self then directs our attentions.

“The self is the most important element of consciousness, for it represents symbolically all of consciousness’s other contents, as well as the pattern of their interrelations.”

Control attention to wake from the dream

I meet people in my consulting and coaching roles who share about feeling like they are “in a dream” and just want to “wake up”. Mihaly’s model clearly explains how this can be the case.

Many people can feel like slaves to their internal and external pressures. When they are hungry, they eat. When they lust, they look or act. When they feel a threat, they worry.

We can find ourselves reacting to the pressures and information of life. Our intention magnet incessantly spins, burning up the scarce resource that is our attention. We can go through life fatigued without fully understanding the root cause.

Mihaly defines consciousness as being distinct from dreaming in that in our dreams we are unable to control outcomes or plan ahead. This describes the lives of many who feel like they have no control or are out of control. This feeling is then expressed in the form of unhappiness, anxiety and depression.

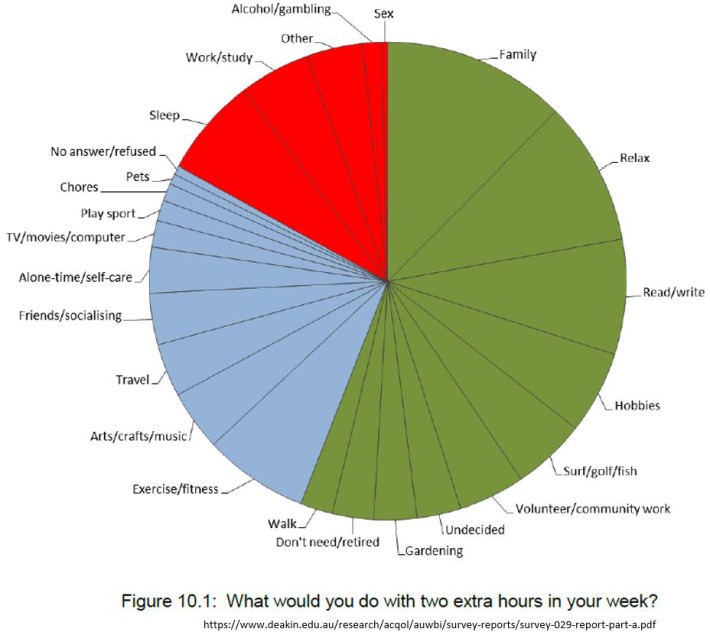

Many seek options to address this stress, often seen as attempts to make our dream state more pleasant. The previous Deakin University research notes that people who are most stressed use interventions such as alcohol or sex to anesthetise themselves, attempt to work more to overcome the issue, or sleep to make the problems go away. By comparison, those who have higher subjective wellbeing invest in various hobbies, relationships with family and volunteering work for something outside of themselves.

It is not so much that we will report higher wellbeing if we do certain things, but that people who own their lot in life happen to make decisions to do similar things.

We can wake from the dream by directing our intentions, guiding what enters our consciousness and owning what happens to the information we experience. The opportunity is to move towards a positive outcome rather than shy away from a real or perceived negative situation.

Waking up from the dream can be both exhilarating and terrifying. Realising we have control also means we become accountable for the outcomes. We are no longer a passenger along for the ride, but we are now the driver. We own our part in the outcomes including our emotional response to the situation.

When I read research on how others have found happiness, I am only mildly interested in what they are doing or the configuration of their life circumstances. These cannot necessarily be replicated to get the same results. I am more interested in how they chose to focus their attention in their life.

I encourage you to explore being aware of the pressures you experience. Understand where you focus your attention. And finally, assess to what extent you own what happens to information as it enters your consciousness. Based on the work of Flow, you can then determine the kind of life you would want to live.

Thank you for directing your precious attention to this post. If you decide this has had some value to your consciousness, please feel free to share below.

Good article: I think you also need to link to the YouTube video where one can learn to pronounce Mihaly Csikszentmihaly’s name. 😉 (Me-high Chick-sent-me-high)

True. Much better than showing people the book simply because I had difficulty pronouncing his name. Now that I can pronounce his name, I am much happier. 🙂