Change lessons from the Holden closure

Car manufacturer GM announced it is ceasing to manufacture Holden vehicles in Australia as of 2017. I reflect on this as an observation of a broad market shift and on the personal impact it will have on a wide range of people. As we wrap up another year, I also consider the personal lessons on how we might develop resiliency to change in an increasingly changing environment.

I grew up in a family manufacturing business, spending a decade of my early career in positions of environmental and safety compliance, operational management, business development, and quality management. I experienced the ups and downs of domestic manufacturing, which eventually saw our 80-person company close its doors due to a lack of resiliency to short-term market impacts from the September 11 terrorist attacks and the paradigm shift of low-cost overseas competition.

My interest in the Holden manufacturing closure is based on a personal affinity for the manufacturing sector and an interest in broader market trends. There are others who have more expertise in the details of manufacturing and in the nuances of technical innovation. If this is you, I welcome your comments and corrections to the conversation.

The situation

Based on a few articles from Australian Financial Review over the past week and around the web, here are a few things we know about the situation:

Known impact

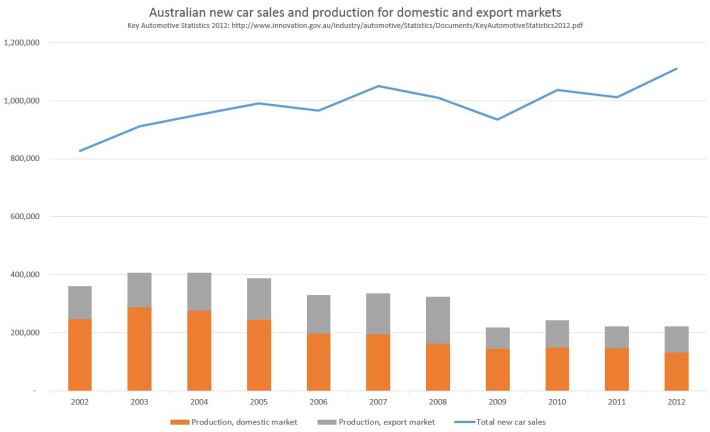

Holden will stop manufacturing in Australia in 2017 after having built its first car here 65 years ago. Around 3,000 direct jobs will be lost. Holden says the minimum economic production of large cars in Australia is 180,000 units per year, but the entire output of the car industry is around 220,000 per year.

Potential or expected impact

If the whole industry collapses, a report by Allen Consulting Group predicts a loss of around 33,000 jobs in Victoria and 6,600 in South Australia. The report states that the economy was $21.5 billion better off as a result of government subsidies and that losing the industry would reduce the Australian GDP by $7.3 billion (out of a total Australian GDP of $1.53 trillion, or an impact of 0.48% of GDP). As part of the Holden closure, the government will be supporting local communities with a $50 million manufacturing transition fund.

Government subsidies

The Australian automotive industry was subsidised by the government. As part of broader cuts, the Australian government removed $500 million in subsidies between now and 2015. Holden was asking for an additional $80 million per year, which would have brought its total financial assistance up to $160 million per year, or $1.1 billion over seven years from 2016 to the end of 2022.

The average taxpayer contribution per Holden built in Australia in 2012 was $2,117. By comparison, the Toyota government contribution per car manufactured was $944.

Toyota

Holden’s departure will place pressure on supply chains dependent on the automotive industry to achieve economies of scale. Toyota uses 70 per cent local content, well above Holden’s 25-30 per cent. The current gap between the cost of making a Toyota Camry in Australia versus Japan or the United States is $3,800.

Plans to close this gap include:

- reducing the 21-day mandatory Christmas shutdown down to 10 days to satisfy export orders to countries that do not celebrate Christmas,

- reduce the pay rate for temporary workers from $850 per week to $814,

- remove the right to permanence after 18 months,

- extend the period of temporary work to three years,

- medical certificates to be provided after eight sick days per year instead of five, and

- address an endemic “long weekend culture”.

The Australian Manufacturing Workers Union is urging workers to vote down the plan.

Toyota employs 4,200 direct employees and 2,500 manufacturing employees in Australia. In 2012, Toyota produced 101,424 vehicles (46% of Australian production) and exported 74,335 units (73% of production). By comparison, Holden produced 89,389 vehicles and exported 12% of its production.

Mitsubishi

Mitsubishi Motors stopped manufacturing in Australia in 2008, giving only three months to their workforce of around 1,000 staff. Acknowledging the different economic conditions of 2008, a survey of 316 Mitsubishi workers found that 72% earned less, 11% earned about the same, and 15% earned more than they did at Mitsubishi, while 11% found work in manufacturing, 7% in construction, 6% in health, 2% in mining, and 2% in defense.

Ford

Earlier this year, Ford closed its manufacturing plants after manufacturing in Australia for 90 years, citing $600 million in losses over five years. Around 1,200 jobs were made redundant, and the government responded with $40 million support too affected communities and $10 million for assistance to affected parts manufacturers.

The local supply chain

Component makers with competitive parts that can access global markets are expected to be in the best position to survive. Suppliers that have not established a foot-hold in overseas markets are expected to face challenges. The government is supporting the parts manufacturers become export-ready with a $50 million export market development grant fund.

The market shift: How many vehicles do we actually need?

I remember in my family manufacturing business when large-volume manufacturing started going overseas in the 90’s. The sentiment at the time that it was like a pendulum; that work would soon return. We were wrong. It was a not a pendulum but a paradigm shift, a fundamental change to business as usual.

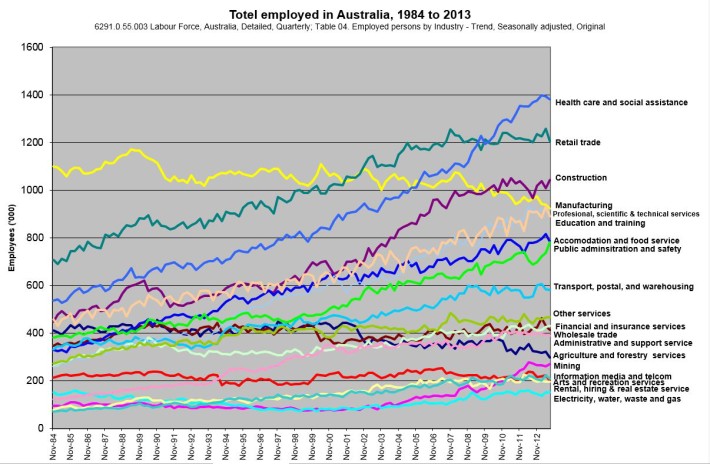

Similarly, three car companies closing their manufacturing doors in relatively rapid succession is a fundamental shift. It is hard to disagree with Jennifer Hewett, editor of the Australian Financial Review, who says that mass manufacturing in Australia is going the way of the rotary phone. The downward slope in manufacturing employment levels is a clear trend.

There are those who say the domestic manufacturing industry could be saved by green technology, robots, 3D printing, and broader economic policy changes. For what manufacturing remains in Australia, differentiating with intellectual property and accessing the export market is critical. For most products, especially cars, the local Australian population is not sufficient to support the volumes needed for economically sustainable production using current margins.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) indicates that around 1.1 million new cars are sold each year, or around 6% of the population of Australians over the age of 16. As we push towards public transport and become more environmentally aware, I question the sustainability of an industry dependent on a growth rate that would match the natural increase in population.

With the previous mention that the domestic manufacturing industry generates 220,000 vehicles per year, this leaves around 81% of the total domestic new car market as imported. There are only so many people who need a new car and they tend to buy imported cars.

The shift in automobile manufacturing is like other market disruptions happening before our eyes. Additive manufacturing, or 3D printing, has the potential to fundamentally change manufacturing processes. Virtual currency Bitcoin is legitimised and is being noticed by central banks (although just as I posted this I see news of the bottom dropping out of the virtual currency market). The Canadian Post is looking to stop home delivery due to falling delivery volumes as customers increasingly go digital. I have previously written about the demise of the compact disc, the changing landscape of social media, workforce disruptions from the IT sector, and other technology predictions. The rate of change continues to increase, spawning lists such as 21 things that became obsolete in the last decade and 10 dying industries to avoid.

It is one thing to read a blog or watch a movies about these changes. It is quite another when it is happening to us and we are the actors involved. The challenge is that no one gave us the script and we are co-creating the plot in our roles as either lead players or victims.

Personal impacts: Everyone’s unique and community is important

I have often asked myself the question: what could you do with several thousand people who have experience working together in a high-performing team, who now have had their purpose removed? Is the purpose the only thing holding them together? Could you give them a new purpose, rapidly build complementary skill sets and leverage their esprit de corps?

This idealistic notion may make good movies, frequently involving zombies or crash landings where a new purpose of survival overrides whatever was previously in place. I expect this is not a practical reality in most situations, however. When I heard the news of then Holden closure, I called two friends who I consider to be experts, one in innovation and the other in career development.

My friend in innovation cautioned me not to treat the employees as one lump number. Each individual will have their own energy and their own outlook that is far from the frame of reference of those assessing the situation from the comfort of their academic or policy-making armchair.

Some employees will take the redundancy package and retire, some will shift careers, and some will find roles in related industries using similar skill sets. Others will have their identity challenged while others will treat the shift as an opportunity to learn new skills. For those with an entrepreneurial bent, the opportunity may be significant to be an active participant in the wider industry shift and be a part of new emerging technologies.

My other friend in career development highlighted the role that communities play in building resiliency. This supports research about migrants who moved into the city to find work. Their success is based in large part to their belief in themselves, which itself is dependent on the extent they have others in their community who believe in them.

Our ability to accommodate change is based in part on our belief that we can be successful in the change, which is moderated by other people’s belief in us. Sometime all people need is to know that there are those who have their best interest in mind and who see them as a success.

Building personal capacity for change

I arrived in Australia in 2000 in my late-20s, having already had two careers in the US Navy and manufacturing. My first point of call was to leverage my experience and ask around to printed circuit board manufacturing companies to see if they were hiring. The response I got back was that they were not looking to improve, were not looking for new customers, and were not looking to bring on new staff. I recall wondering what I was good for if I could not do what I had experience doing.

I then stumbled on the book What Color is Your Parachute?, which walked me through a process of asking myself what it was I wanted to do and pursuing informational interviews to validate my response. After calling about a dozen multimedia companies and meeting with about half of them, one of them offered me a job and I started my next career.

This sounds easy on reflection, but the process was filled with insecurities and uncertainty. Having made a few additional jumps since then, I can attest that change becomes more familiar but I doubt I will ever call it easy. I will also attest that all of my changes in life have had my wife believing in me along the way, which makes it easier for those times you stop believing in yourself.

I consider my recent post on Flow, which highlights the role that challenging tasks have on our sense of life enjoyment. If we perceive the challenge as greater than our skill, then we can feel anxiety. Too much anxiety and you see fear-based responses such as blame and accusations. However, if we build up our skills and believe we have the skills to meet the challenge, then we can find enjoyment in most things.

I do not minimise the challenges ahead for the manufacturing industry and those directly affected by Holden’s shut down. At the same time, I am conscious of other industries such as segments of agriculture and retail just as challenged. Even as I write this, I see the announcement today of retailer Robin’s Kitchen’s liquidation, closing 55 stores before Christmas and affecting 300 staff who will not have access to the same redundancy packages as Holden employees. Change is the constant factor in our future.

As I look ahead to the coming year, I consider:

- How to seek out challenging and new situations to build personal resiliency and prepare for change;

- How to develop skills to help others facing their own change situations and support them by believing in them;

- How to predict and prepare for broad market shifts; and

- How to build strong community networks to co-create the future state where we all can live to our full potential.

I invite you to ask similar questions, comment and share below, and come along on the journey as you define for yourself what success looks like in your next 12 months. I also invite you to share and invite others along using the links below as we work together to make the world a better place.