How do you measure your self-esteem?

I am becoming increasingly aware of a tendency in society (or perhaps myself?) to associate self-worth with our performance or position. This can result in all sorts of defensive behaviours when people get under pressure or are exposed to change situations.

Here’s a few things I uncovered about self-esteem in my last post:

- Happy people can have high self-esteem, but having high self-esteem does not mean you’re happy.

- Self-esteem that is based on being better than others or your performance can make you miserable.

- Healthy self-esteem is based on setting our own goals, learning from the process of achieving those goals, and having goals that are for something bigger than ourselves.

- Our self-esteem is largely based on our upbringing, and our self-esteem will likely be similar to the self-esteem of our parents.

- Because of the connection between our upbringing and our self-esteem, mentors can act as an external catalyst to help us develop healthy self-esteem, helping show us how to set goals and point us to a purpose that is bigger than ourselves.

These points and the supporting research, along with a few conversations I have been having about the post, are highlighting a practical model of self-esteem.

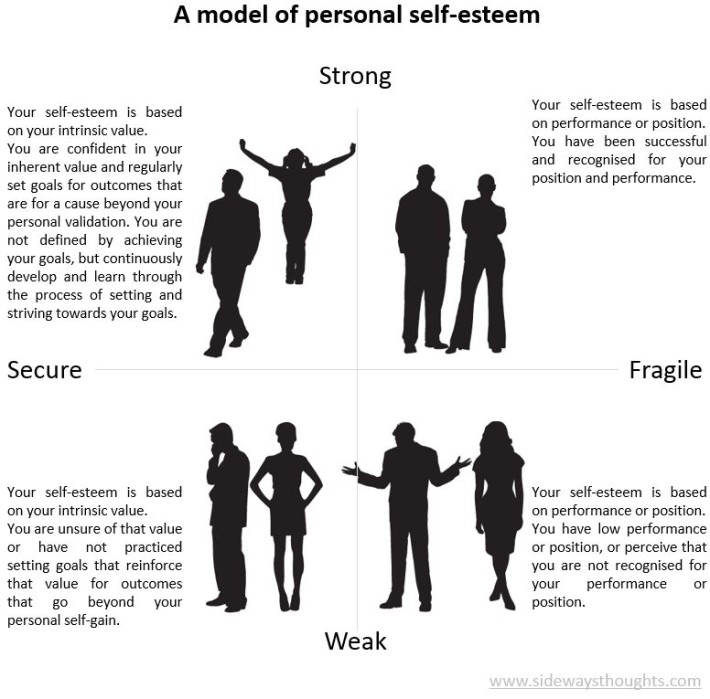

Fragile versus secure self-esteem

One of the research articles I found from my last post said our self-esteem is either fragile or secure, depending on the source.

Fragile self-esteem often comes from external sources such as:

- validation of our performance,

- our relative position to others, and

- our membership in a group, team, organisation – including profession, religion, family, political party or community.

Secure self-esteem on the other hand comes from within; an awareness of our intrinsic value. Goals play a role, but only if the goals are an expression of our value rather than our value being defined by our goals. This intrinsic value often has spiritual elements, as people integrate spirituality into their view of self.

This integration is evident in what one researcher defines as Universal Worth, which is based on the belief that:

- one is valued by a deity;

- one’s value is not contingent on success or failure; and

- one is not valued by a deity more or less than others are valued.

This distinction of source as internal or external is also seen in another study that defined seven sources of self-esteem in college students:

- Competency – specific abilities like academic competence;

- Competition – outdoing others;

- Approval from generalized others – the perception of others’ esteem;

- Family support – refers to perceived affection and love from family members;

- Appearance – self-evaluations of one’s physical appearance;

- God’s love – the belief that one is valued by a supreme being; and

- Virtue – adherence to a moral code.

Self-esteem from external sources such as competition or approval from others could be seen as fragile, whereas self-esteem from virtue or a belief in inherent value could be seen as secure.

Defining a model: Fun with Jane

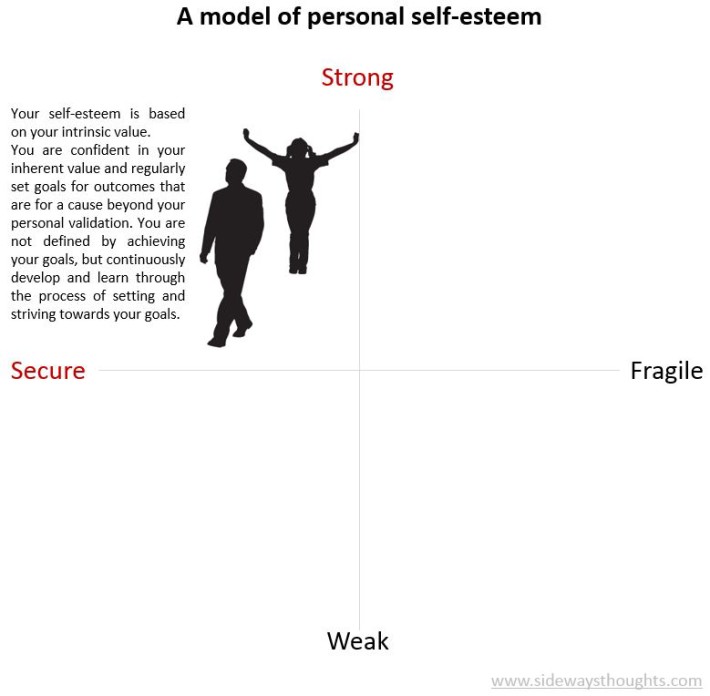

Both secure and fragile self-esteem can also be seen as being either strong or weak. This results in four combinations:

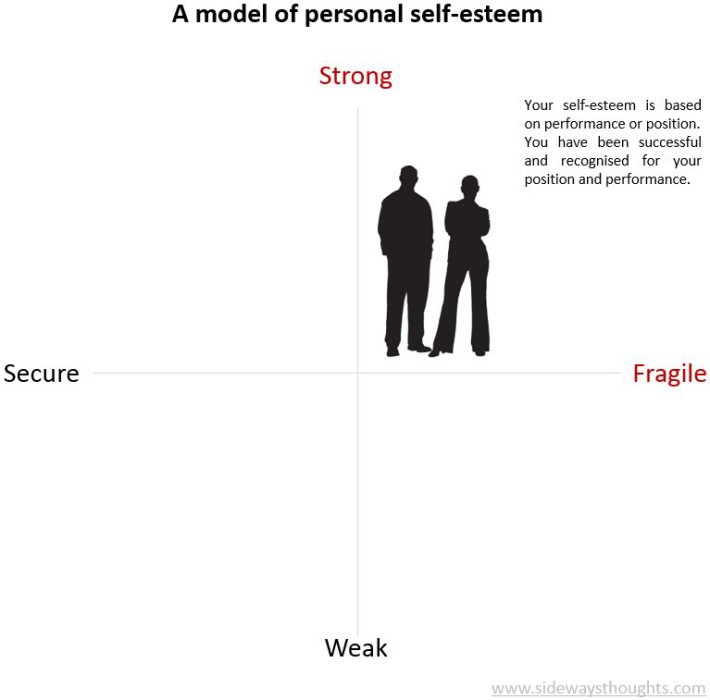

Combination 1: Strong and fragile

Let’s take Jane for example. Jane has always been a high-achiever whose self-worth is defined by her position and performance. Jane has led a charmed life and now in her 30s is in an enviable management position in a high-profile technology company.

Jane perceives any risk to her position or threat to her company as a personal attack. Her response to these threats is aggressive and defensive behaviour. Jane’s self-esteem could be considered strong, but fragile as it is based on things external to Jane that she does not control.

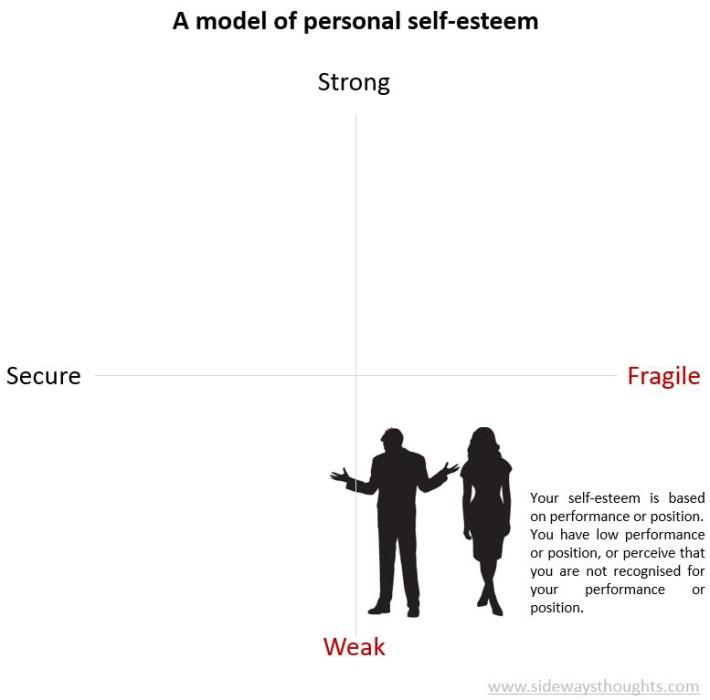

Combination 2: Weak and fragile

At some point, Jane may hit the proverbial wall. She may lose her job, experience burnout, and push away those close to her in her search for success. She may perceive these experiences as personal failures that reflect on the value she has as a person.

Jane still defines her self-worth from her performance and position, but she is no longer recognised for these things. Jane’s self-esteem is still fragile, but now it is also weak.

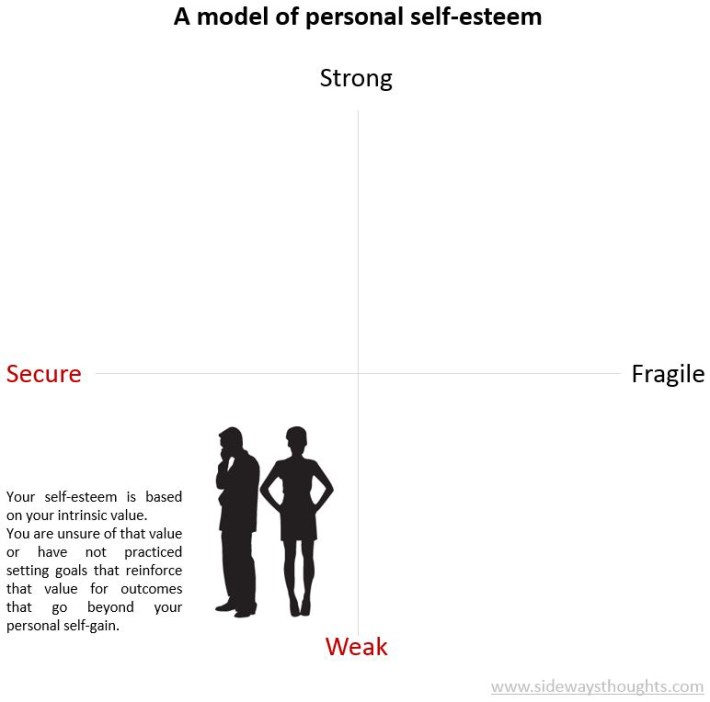

Combination 3: Weak and secure

Jane, though her struggles and perhaps insight from a mentor or coach, may become aware that her performance and position do not define who she is as a person. After losing almost everything that defined her, Jane is left with a growing understanding of her value that is inherent to each of us as humans apart from how we perform or our position in life.

Jane begins to explore her worth based on who she is, apart from what she does. While previously Jane’s goals were about power and winning, Jane now starts setting goals that are simple but aligned with who she is. Jane’s self-esteem becomes more secure but it is weak and untested.

Combination 4: Strong and secure

Jane’s character continues to be developed as she sets her own goals apart from what other people think or her perceptions of other’s opinions. She begins to seek out opportunities to grow and develop. She may or may not be recognised, but she continues to learn and develop as a person.

The goals Jane sets continue to evolve beyond her own aspirations based on a realisation of her place in the world not at the top of a ladder but as part of a whole. As she becomes more practiced, Jane’s self-esteem is secure and becomes strong.

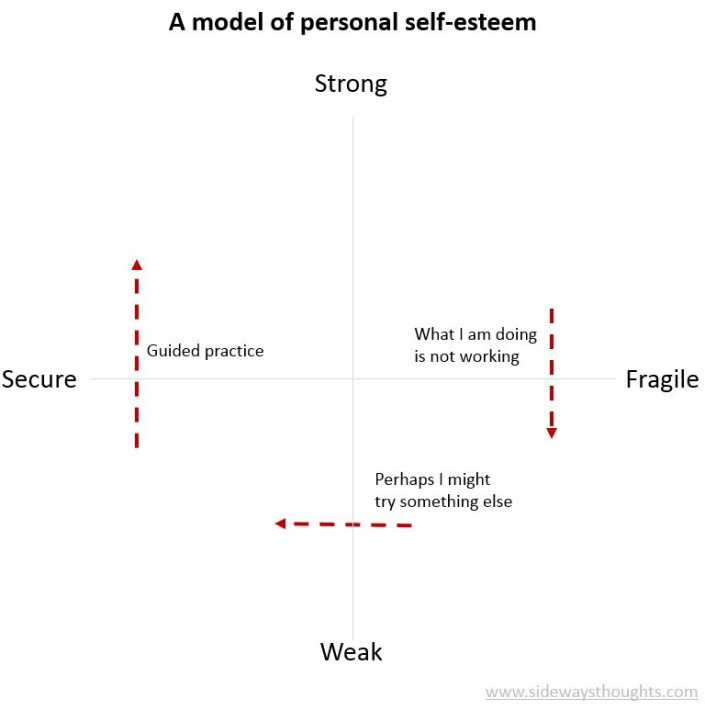

Self-esteem transitions

The narrative above reflects a transition that is common in a driven workforce. People who define themselves by their success encounter a crisis when the measures of that success are no longer favourable. That crisis prompts reflection and an awareness of their value outside of their achievements as well as something greater than personal aspirations. Applying the self-esteem quaderant model, this presents a “U” shape transition of breaking down fragile self-esteem and rebuilding secure self-esteem.

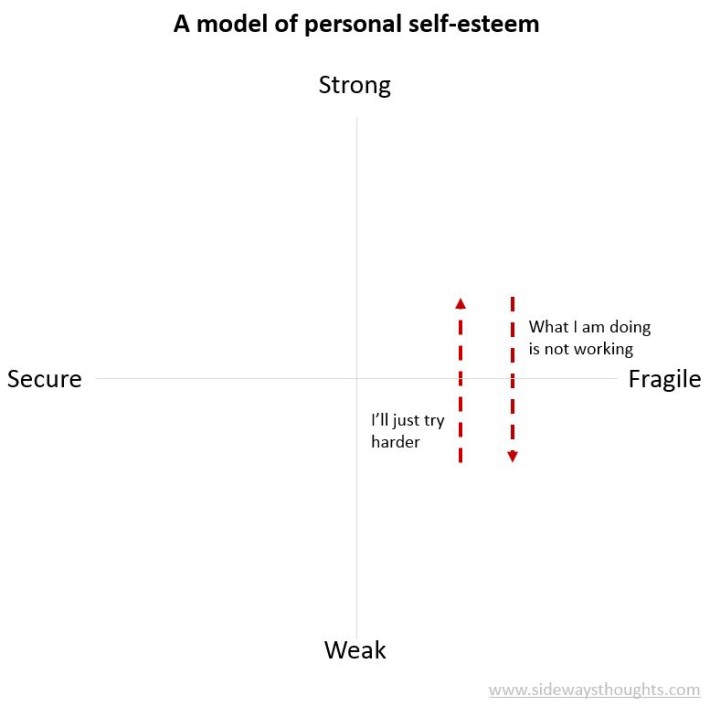

There may be other transitions as well. For example, some people may continuously transition between strong and weak fragile self-esteem in an endless loop. Their response to things not working for them may be to simply do the same things faster and harder.

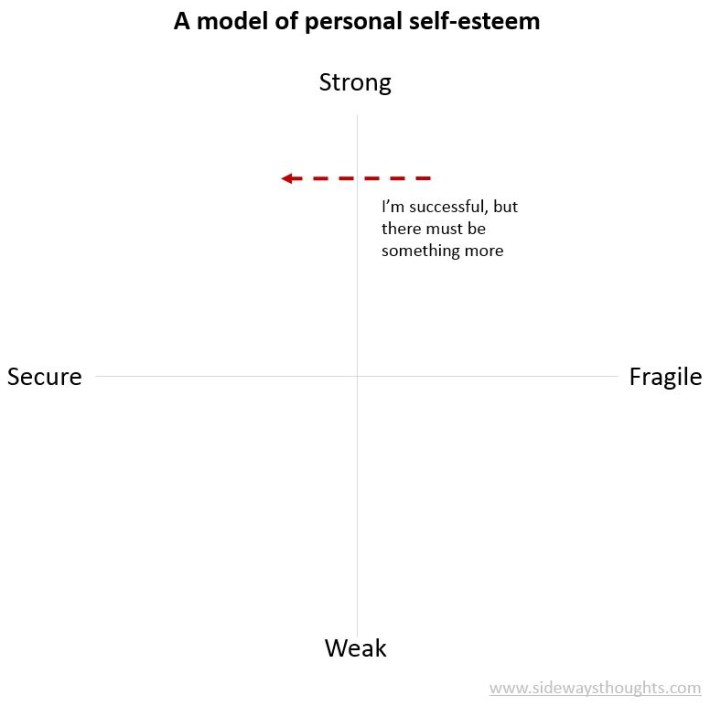

Still others may be at the peak of success and find it empty. They may not need to have a crisis, but an event or conversation may prompt them to re-evaluate the source of their self-worth.

Applying the model

Where would you place yourself on the model? Where do you get your self-worth?

One of the reasons why I am a fan of models is that they are able to take aspects of ourselves that are often hidden such as how we define our self-worth and present them in a practical way that can be observed. Once observed, we become aware of it, decide the extent that it reflects reality, and make choices that can help us be more effective and live a full life.

The other thing I appreciate about the model is that it is very clear about what is required to move into strong and secure self-esteem. If you set your own goals for a purpose you perceive is bigger than your own personal gain, then you inherently begin to become more effective and define a healthier perspective of self-worth.

Who you are as a person has value, simply because you are you. Your achievements do not define you. Your performance does not define you. Your position does not define you. I acknowledged in my last post that simply telling you this may not change your own views of your self worth. It is my hope that perhaps seeing a model may help a few people understand practical steps to move towards a healthier perspective of self-esteem.

As I also mentioned in my previous post, this process is often facilitated by someone external to help guide you on the way. If you are such a guide and you know someone who may benefit from considering a healthy perspective of self esteem, please feel free to share through the social links below.

3 thoughts on “How do you measure your self-esteem?”

Comments are closed.