Organisational ambidexterity: How to exploit and explore to survive

The hallmark of our age is the tension between aspirations and sluggish institutions. – John W.. Gardner

Change and tension

There is a tension in the natural exchange between equilibrium and change. On the one hand, we have a tendency to move towards comfort and stability. On the other hand, that stability produces a complacency that ill-prepares individuals, institutions, and societies for inevitable change. It is also often through instability that we experience meaningful growth.

We see this model play out in various contexts. The pattern appears in politics through changing political parties, unrest and revolution. We see this as individuals experience life-transitions, epiphanies, and the cliché of the “mid-life crisis”. In nature, we see the cycle of the seasons punctuated by natural disasters and global shifts. Finally, we see market leaders in organisations rise and fall through the cycles of technological, political and social disruptions.

It is often the smaller, more nimble entities in these situations that thrive while the large dominant player that has adapted to the current situation becomes extinct. Small, adaptable mammals replaced the dinosaurs in the same way that agile start-ups overtake large, bureaucratic institutions in times of environmental upheaval.

While some might say this transition is inevitable and the old give way to the new, a prescription has emerged for organisations looking to be resilient in times of disruption. For organisations to survive and even thrive in a turbulent landscape, they must become what is referred to as ambidextrous.

Juggling two perspectives

The concept of the ambidextrous organisation was made popular in a 1996 article titled “Ambidextrous Organizations: Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change” by then Harvard professors Michael Tushman and Charles O’Reilly III. Their article explored the rise and fall of technology companies over 40 years to understand how organisations adapt to change. The companies that succeed, the author’s noted, were able to balance the tension between exploitation and exploration.

|

Organisations that engage in exploitation mine the depths of their core strengths, making the most of the resources they have. They focus on efficiency and productivity through capitalising on core strengths and differentiators. Change is minimised, conflict avoided, and identity is reinforced and protected. |

|

Organisations that focus on exploration on the other hand cast their gaze upon the horizon, discovering new resources and finding new ways of doing things. The focus is on innovation and learning through acceptance of failure. Change is pursued, conflict embraced, and new identities are considered. |

Organisations who wish to be resilient to change must become ambidextrous, to have the capability of engaging in both exploitation and exploration. They must learn to leverage existing customers and assets while discovering new markets, new products, and new approaches. This can make business leaders feel as though they must become respected jugglers, as noted by the professors:

“A juggler who is very good at manipulating a single ball is not interesting. It is only when the juggler can handle multiple balls at one time that his or her skill is respected.”

Three approaches to being ambidextrous

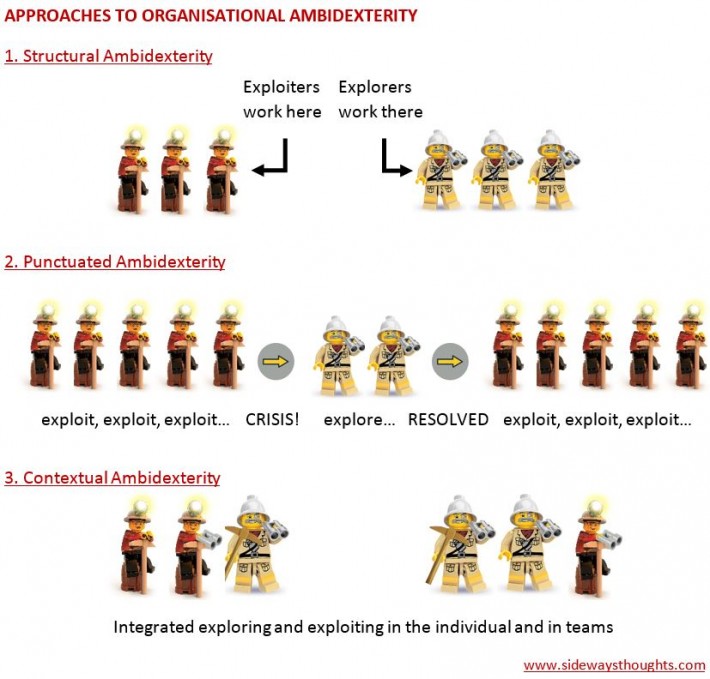

The juggler is not necessarily doing multiple things at once, but is aware of the need for different perspectives. Many leaders intuitively know that both exploitation and exploration are needed, but they feel like they are already trying to keep so many balls in the air that introducing yet another perspective is not possible. So they try to isolate exploring or exploiting perspectives by either space (structurally) or time (punctuated).

- Approach 1: Structural ambidexterity

One approach is to physically separate the two functions of exploration and exploitation. This is like juggling with two hands in isolation of each other, never throwing the ball from one hand to the other. We often see this in the creation of Research and Development teams or separating start-up business units from a larger organisation. - Approach 2: Punctuated ambidexterity

A second way is to separate the two functions by time, often involving long periods of exploitation punctuated by short bursts of exploration. This can be reactionary rather than strategic, as the organisation feels forced to respond to a dramatic internal or external change. It is like a juggler only being able to juggle at certain times, and being incapable of juggling at other times. - Approach 3: Contextual ambidexterity

Each individual has a behavioural orientation towards the dual capabilities of exploring and exploiting. The juggler can juggle at any time or all the time, with different types of objects going from one hand to the other.

It is in this third approach that research shows is most effective. Relying solely on the structural or punctuated approaches can result in innovation becoming something that someone else does or relegated to that other department or that thing we did last year. The contextual approach taps into the collective ideas of the organisation and has the potential to engage the hearts, minds and actions of each person.

How to be ambidextrous

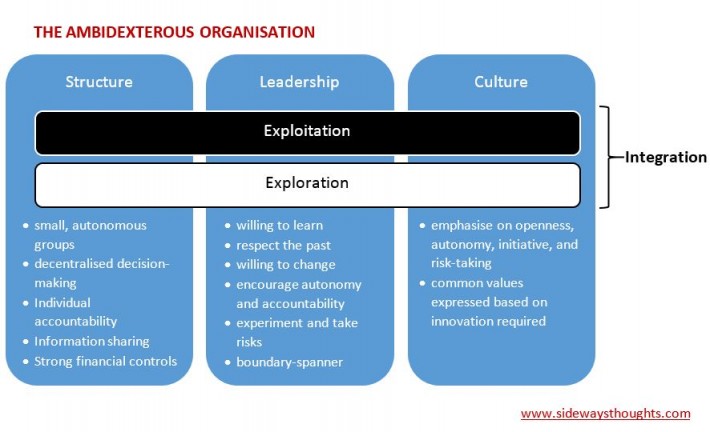

Being able to both exploit and explore at the same time is necessary for flexibility and resiliency, but it does not happen automatically. In search for specific prescriptions, I reviewed 25 research articles published in the past ten years. The conclusions from the papers focused on three areas: structure, leadership and culture.

Characteristic 1: Structure

The structure of the ambidextrous organisation balances freedom and autonomy with strong controls where they are important. The structure accommodates small, autonomous groups with decentralised decision-making and an emphasis on individual accountability, information sharing and strong financial controls.

Practically, the structures incorporates project-based sub-structures and small, self-managed teams who have a clearly defined purpose. The teams have a clear line of sight to the organisational vision and strategy. The emphasis is on generalisation rather than specialisation to allow for people to shift to new areas and skill sets as needed. Where specialisation is necessary, there are dedicated functions to help share knowledge and achieve synergies between knowledge centres.

Characteristic 2: Culture

The culture is described as being simultaneously both loose and tight. “It is tight in that the corporate culture is broadly shared and emphasises norms critical for innovation such as openness, autonomy, initiative, and risk taking. The culture is loose in that the manner in which these common values are expressed varies according to the type of innovation required.”

The culture avoids defensive passive or aggressive fear-based responses. This requires a more secure, long-term perspective, which is often contrary to the short-term demands of the market. People know who they are in the organisation, what they should be doing, are given the latitude to do it, are secure in their ability to learn from feedback, and encourage each other as part of a team through the journey.

Characteristic 3: Leadership

The leadership in the ambidextrous organisation is characterised by a willingness to learn, avoiding arrogance, and respecting the past but willing to change continuously to meet the future. The leaders promote variation through strong efforts to decentralize, to eliminate bureaucracy, to encourage individual autonomy and accountability, and to experiment and take risks.

An example a tolerance for failure is described as a seven-to three-formula. It is better to make decisions quickly and be right seven out of ten times than waste time trying to find a perfect solution. The culture, structure and leadership embrace continuous learning and agility aligned to a shared vision supported by strong controls and accountability.

Of the three characteristics, leadership is the area that can have the most influence. As one researcher noted:

“There seem to be fewer problems installing adequate structures for organizational ambidexterity compared to implementing these new structures in the mind of the innovators and top management.”

A form of leadership is required to act as a boundary spanner, an enabler function linking the different business units. This can be an individual, a team, or a function of a role who acts as a process promoter, overcoming barriers of non-responsibility and non-communication between organisational units. They are referred to as a navigator of the innovation process and mediate between hierarchical and functional levels of the organization. Leaders who are successful in managing the dual functions have a collective sense-making, a common mindset, and a broad background knowledge on diverse tasks.

Integration key to being ambidextrous

The research acknowledges what leaders and managers already know: that focusing on both exploration and exploitation takes effort and resources. The challenge highlights the appropriateness of using ambidexterity as a metaphor. You may feel awkward and even embarrassed if you try to write with your non-dominant hand. It does not feel natural and you may find yourself reverting back to what feels natural.

Simply being good at both exploration and exploitation is not enough. You also need to be able to integrate the lessons learned from the activities. Leaders can have a tendency to become narrow focused, exploiting change capabilities without exploring the appropriateness of applying those capabilities. Much of the literature on ambidextrous organisations reinforces that “a reintegration of the exploratory business unit in the exploitative structure was necessary in order to guarantee the success of both the exploratory and exploitative units.”

Like many remedies, it is most difficult when you need it the most. Another researcher observed in his case study that:

“The greater the turbulence, the greater the need for integration and the less likely it will occur.”

We are seeing organisations embrace the principles put forward by the research. I recently attended a conference where I heard from a representative in the Royal Australian Navy share about their New Generation Navy culture program that was built on the three pillars of structure, leadership and culture. I also heard from Australian Weet-Bix food manufacturer Sanitarium share about their award-winning culture program, and how a “perfect storm” of market disruptions in the market forced them to explore new products, create parallel lines of development, and integrate new thinking with business as usual for innovation.

Established companies are often forced to embrace the premise of the ambidextrous organisation in times of crisis. Perhaps the opportunity is to focus on the appropriate structure, leadership, and culture and integrate exploring and exploiting to be resilient before the crisis comes.

Juggling Image: Five Salty balls by Gabriel Rojas Hruska

3 thoughts on “Organisational ambidexterity: How to exploit and explore to survive”

Comments are closed.