Seven lessons in personal freedom from Nelson Mandela

Freedom: The power or right to act, speak, or think as one wants.

There is a belief that the more freedom we are allowed, the more likely we are to take advantage of that freedom. Yet people who have many freedoms can still feel “trapped”, “stuck”, or slaves to their habitual responses.

Two forms of freedom

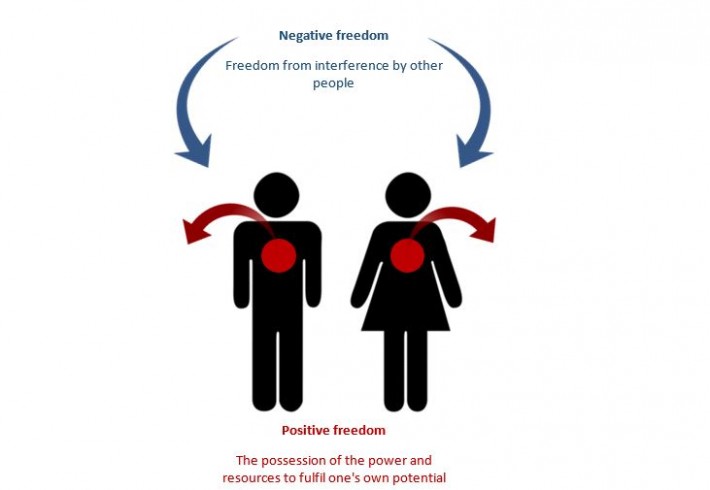

There appears to be two different types of freedom. This is the same conclusion made by Oxford philosopher Isaiah Berlin in his 1958 lecture Two Concepts of Liberty.

Berlin distinguished between what he referred to as positive liberty and negative liberty. To have positive liberty means that a person has within themselves the power and resources to fulfil their potential. Negative liberty by comparison represents a freedom from external interference from others.

Much of what we think of when we talk about freedom applies to negative liberty. This freedom from having external limitations placed upon us is the focus of various research projects that rank countries and states by degrees of freedom. These projects look at economic freedoms, security and safety freedoms, freedom of movement, freedom of expression, and various freedoms in relationships.

One of these lists, the Fraser Institute’s Towards a Worldwide Index of Human Freedom, ranks my current home-nation of Australia as the fourth freest country in the world. I look at this position in the top 3% of the list of 123 countries and acknowledge that I have not felt a true loss of negative, or external, freedom relative to other countries at the bottom of the list.

There are, however, lessons to be learned about our internal freedoms from leaders who have fought against a loss of external freedoms. It is as though the men and women who had the most liberties taken away from them by others had a greater capacity to discover a freedom within themselves. There appears to be a connection between a struggle against external constraints and the development of internal freedom.

Seven personal freedom lessons from Nelson Mandela

One leader who epitomised this struggle was Nelson Mandela. In his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela shares his journey of awareness about his loss of freedom and embracing his role as a Freedom Fighter. The freedoms Mandela fought for fall clearly in the negative liberty definition, of being free from the external limitations placed upon the black people of South Africa by the whites under the practice of apartheid.

Mandela faced many challenges to simply survive, much less attain an education, establish his own law practice, and commit to leadership in a political party that would eventually see him be tried for treason, go underground, and spend 27 years in prison. Through the sharing of his journey, Mandela highlights several powerful life lessons about what it means to be personally free:

1. Losing freedom can be a gradual process

The loss of freedoms experienced by the non-whites in Africa was gradual. Laws were slowly introduced that had escalating impact. The Nationalist government promoted that the segregation and restrictions were in the best interest of the black people. This was reinforced by a message that blacks were incapable of achieving the same level of education and sophistication as the whites.

Losing our own personal freedom is a similar, subtle process. It is not the Nationalist party but our own narrative that can limit self-belief. This process may stabilise to a level that is manageable through learned defensive responses, or it may continue until radical action is needed.

2. Regaining freedom can require planned radical action

Mandela does not point to a single day when he became a Freedom Fighter, but highlights a lifetime of discontent that culminated into action. Mandela eventually established a militant arm to launch attacks to fight for freedom. The group had a defined structure, clear accountabilities, autonomy, and a policy for behaviour. He considered four options of sabotage, guerrilla warfare, terrorism, and open revolution. Of the four, sabotage was preferred based on it offering the best hope of reconciliation afterwards due to not posing a loss of life.

In the same way, individuals may need to take intentional action to realise their own personal freedoms. This can often come in the form for a “crisis”, as the person throws off the limitations they have placed upon themselves or a need to re-establish boundaries in their life. The response can seem like a radical change, but radical does not mean a personal fight for freedom is not planned. Care can also be taken to consider the impact on others as boundaries are clarified.

3. Freedom comes with having a purpose

Mandela reflected that:

“I nevertheless felt a great sense of accomplishment and satisfaction: I had been engaged in a just cause and had the strength to fight for it and win. The campaign freed me from any lingering sense of doubt or inferiority I might have felt; it liberated me from the feeling of being overwhelmed by the power and seeming invincibility of the white man and his institutions. But now the white man had felt the power of my punches and I could walk upright like a man, and look everyone in the eye with the dignity that comes from not having succumbed to oppression and fear. I had come of age as a freedom fighter.”

The fight and purpose it brought freed Mandela from his sense of doubt and inferiority, sentiments he speaks of throughout his story. The fight for personal freedom can also bring with it a pride. The pride is not in being better than others, but in being your best self and not succumbing to fears we may place on ourselves.

4. Freedom requires both knowledge and action

Mandela spoke of the need for both education and action. On the one hand, the government’s policy of limiting education could be seen to intentionally keep the black people in control:

“Only mass education would free my people, an educated man could not be oppressed because he could think for himself.”

And yet education is only effective when there is action. Mandela valued education but also spoke of his realisation that many of the people he respected for their practical achievements lacked academic degrees.

“Education was essential to our advancement, but no people or nation had ever freed itself through education alone.”

Education plays a part in the fight for personal freedom. There is value in being aware of the reasons behind our own beliefs and actions as well as those of others. That awareness has little value if not supported by acceptance and action.

5. Freedom requires a fight

Mandela speaks of the value and cost of freedom:

“The African people knew that a nonviolent struggle would entail suffering but had chosen it because they prized freedom above all else. People will willingly undergo the severest suffering in order to free themselves from oppression.”

Most personal growth requires a level of discomfort. This can be at odds with a society that caters for our comfort and complacency. If personal freedom has value, then it is worth being uncomfortable; it is worth fighting for.

6. Freedom requires discipline and consistency

Mandela’s story is characterised by a disciplined approach to the freedom struggle. This was a learned behaviour and a characteristic he cultivated through his life:

“The freedom struggle required one to make compromises and accept the kind of discipline that one resisted as a younger, more impulsive man.”

“Only through hardship, sacrifice, and militant action can freedom be won. The struggle is my life. I will continue fighting for freedom until the end of my days.”

Nelson Mandela spoke of his personal disciplines both physical and mental. This appears to be a theme common to great leaders. If you want consistency in realising goals in personal freedom, then perhaps one way may be to learn discipline in seemingly non-related areas of your life. It can be through the sacrifice that is required from personal discipline that freedom is found.

7. Finding freedom is about finding who you are

At the age of 44, Mandela was sentenced to life in prison, against which he served 27 years. He shares about how the prison system attempts to take away everything that makes a person who they are, relegating them to a number:

“Prison not only robs you of your freedom, it attempts to take away your identity.”

People who struggle with personal freedom often share about not knowing who they are anymore, having not chosen their lot in life, and needing to “find themselves”. The prisons we create for ourselves can take away our identity, reducing us to a character of ourselves.

Getting out of jail

The freedom provided by nations can be seen as a metaphor for the freedoms we provide ourselves. Each of us are in unique situations and the responses to increase our freedom can be different. The government we are fighting can be the governing processes of our own minds and emotions.

There are a few tools that can us help navigate through understanding how we view our personal freedom, such as the Life Styles Inventory I recently posted about. As a starting point, a few questions may help test some of the points outlined above:

- Have I been gradually giving up my freedom? If so, what would it mean to take it back?

- Can I put a plan in place? What small, consistent steps can I put in place to regain those freedoms?

- Is my freedom a just cause I am willing to fight for?

- Do I have the knowledge I need? What feedback am I receiving? Am I taking action on that information?

- Do I feel constrained, like I am in a prison of my own choosing? Or is my approach to personal freedom allowing me to be who I know I can be?

- What small, consistent disciplines can I put in my life? Can I make a commitment to a small change towards a greater outcome?

When it comes to personal freedom, we can be the warden of our own prison. It is to this point that Mandela provides perhaps the most important lesson. In the introduction to his autobiography, Mandela is quoted reflecting his thoughts towards his captors as he got into the car on the day of his freedom:

“If I still hated them, they would still have me. I wanted to be free, so I let it go.”

As you reflect on the extent of your own personal freedom, remember to be kind to yourself. Mandela’s last thoughts as he left prison may be your first step towards finding a way out.

1 thought on “Seven lessons in personal freedom from Nelson Mandela”

Comments are closed.