The humanity challenge: Prioritising the purpose of profit

Prioritising five ways we spend our money

Where do you spend your money?

Regardless of how much you make and whether it is for yourself or your organisation, you likely invest in one of five areas:

- Survival

We spend some of our money on simply staying alive. For the individual and for business, profit is an indicator of life. If the energy you expend is greater than what you consume, you will eventually starve and die.

- Payout or reward

Once we get enough to survive, we may give ourselves a payout or reward. The line between survival and reward can blur. What one person may see as a reward, others may view as a survival item (“If I don’t have that latte/shirt/holiday/music, I will just die!”).

- Capital

The survival / reward cycle can be expanded to include investing in capital to allow a greater future return for a present day investment. As I noted in my post about the nature of capital, those who are in the upper bands of wealth tend to use this approach to maintain their financial position.

- Generational

As people get older, there may be a growing awareness that at some point they may cease to exist. The focus of their profit then turns to their legacy, often in the form of passing their wealth to their children or those they connect with.

- Humanity

Finally, we can spend our money on things that are not for our personal survival or our immediate families. Charity and investment into community are likely the first options that come to mind. We can also include taxes in this category as a forced payment for something outside of ourselves.

Giving to ourselves and giving to our own

The first three approaches of survival, reward and capital investments can be seen as a natural self-sustaining evolutionary response. We look after ourselves now and into the future.

Inheritance is similar, except that it is looking beyond ourselves to our immediate tribe. It is understandable to look after our children, but this generational passing on our reserves also contributes to systemic inequalities of wealth. Over 60 percent of the 2012 Forbes richest 400 grew up in substantial privilege. By 2020, around 70% of wealthy individuals will come from inherited wealth. Amassing large amounts of wealth usually takes more than a single lifetime, and it helps to have a head start

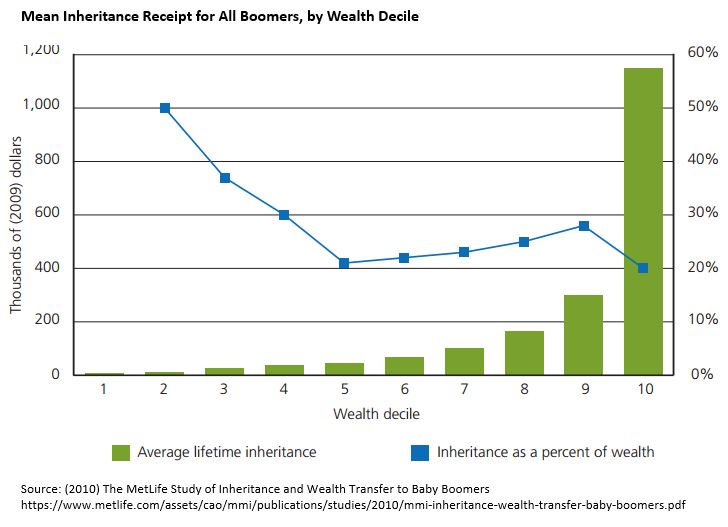

A 2010 MetLife study on inherited wealth in the United States noted that US$8.4 trillion is expected to be passed down to the Baby Boomer generation. The distribution of this income is highly unequal. The top 10% of the wealthy receive an average of US$1.5 million in inherited wealth compared to an average of $27,000 for the lower 10%.

The inheritance is more meaningful to those who earn less. For top earners, the amount that is inherited represents an average of 22% of total household wealth. By comparison for the lower 20% of the wealthy, the inheritance can represent up to 64% of total household wealth.

Given that inheritance provides a greater relative contribution to those who earn less, you would expect that passing money through families to lower-income segments in society would close the gap between the poor and the wealthy. The “eventually” would take many generations, however, and does not account for massive disruptions as well as deep and complex challenges facing different societies.

Giving to others

Addressing the challenges of the world requires giving to more than just our immediate family. According to the recent World Giving Index, around 20% of the world’s population donate money to charity. This is a problematic number to compare across countries.

In 2012, around 65% of Australians donated an average of 0.33% of their income to charity. That’s $231 for a $70,000 per year salary. By comparison, a Giving USA report shows that over 95% of Americans gave an average of 3 percent of their income to charity, which is around $2,100 for the same previously mentioned $70,000 per year salary. (I expect the amount given to be slightly higher, as this number only counts money claimed on tax returns.)

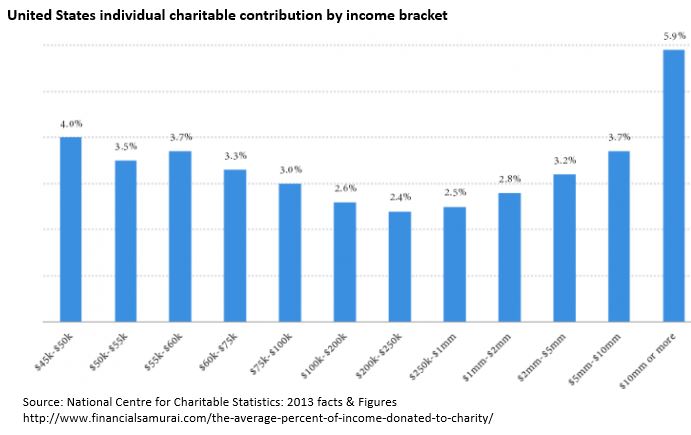

There are a few reasons why some countries give more than others. A 2006 report on international comparisons of charitable giving identified differences in personal taxation as a contributing factor for differences in giving. People living in countries that have higher taxes tend not to give as much to charity. This also plays out within the same country where people in certain income bands pay more tax than others. For example, the middle class in the United States are referred to as being “stuck in the middle” at a higher tax percentage on their taxable income and give a smaller percentage of their salary than those in upper or lower income brackets.

This is why I include taxes as a form of forced giving to humanity. Through taxes, we hand over to the government the decision on how we should spend our money. Investments such as roads and other infrastructure, education and health subsidies, market growth incentives, and foreign aid provide a means for making the world a better place.

The government then becomes the administrator of our charitable distribution. If those funds are not allocated in areas we believe are improving our community or humanity in general, we can lobby the government, change the government (through revolution in a dictatorship or voting in a democracy), or spend our own money in different areas we believe in. Taxes allow for effective distribution of funds, but it can also mean money is diverted to special interests and can miss disadvantaged segments of society.

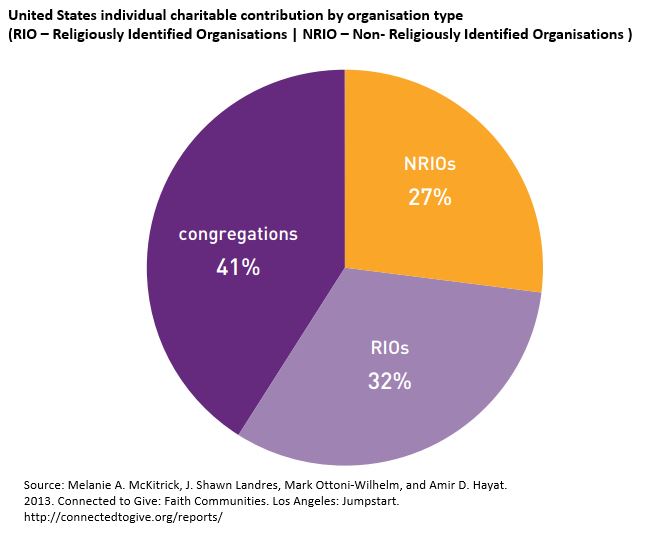

The approach to religion is also a contributing factor in how money is spent. Some religions such as Christianity use tithe to legislate or prescribe the act of giving a percentage of income. A report from Connected to Give on charitable giving in the U.S. identified that 41% of charitable giving was to religious congregations, 32% was for Religious Identified Organisations (RIO), and the remaining 27% was towards Non-Religious Identified Organisations (NRIO). If an American is going to give, they are 73% more likely to be towards a religiously-affiliated organisation.

This is where we see a relationship between tax and tithe. Giving money to a registered not-for-profit, spiritual or otherwise, is deemed as tax “exempt” for the charity and can result in a tax “deduction” for the individual. Governments providing allowance for religious or other charitable institutions can be seen as an acknowledgement of the role of the tithe as performing a similar function as taxes to fund the good of humanity.

The benefit of giving to others

The way we spend our money presents a paradox. On the one hand, we have an instinct to survive. We leverage our spending to store up reserves and compete with others for scarce resource. On the other hand, we are psychologically wired to have greater enjoyment in life when we give to a purpose outside of our own gain.

Giving to a purpose outside of ourselves is a premise in most psychological models of personal development. In a previous post I outlined research that shows how setting goals for a greater purpose outside of personal gain is associated with secure self-esteem. Approaches such as Kohlberg’s model of ethical decision-making or Maslow’s depiction of peak experiences identify that doing things outside of personal gain is a desirable higher-order to be attained. The health benefits of giving time in the form of volunteering are well documented. In my own experience as a coach and facilitator, those I work with often benefit from finding a cause outside of their immediate needs.

Our society provides a lot of respect for people who show these values. Individuals such as Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi are revered as those who sacrificed personal gain for a cause outside of themselves.

We even acknowledge the need to give in corporate circles, a view contrary to earning profit solely for self-interest. In a 2014 report on “Combining profit and purpose”, the Chairman and CEO of Coca-Cola highlights findings that:

“Current CEOs of major European businesses and those we expect to be the future leaders of our businesses… firmly believe business should provide value to society above and beyond a financial return to shareholders. They believe successful organisations take a holistic approach to how they define value, seeking ‘shared value’ between profit and wider society.”

The humanity challenge: The real purpose of profit

Security is essential, rewarding ourselves is part of enjoying life, and building up capital for greater future returns is important. It is also understandable to want to leave an inheritance, taking care of our families for future generations.

As I consider the priority of my own approach, I ask what would it look like to turn spending priorities upside down? Rather than focus first on self-preservation and reward as an end in itself, what would it mean to have conversations about how we might best spend our money for the betterment of humanity? What if the reason why each of us is here, and the reason why we make money, is to have a positive impact, ending our time on the planet with humanity in a better place than when we started?

Do we need to be very wealthy like Bill Gates or Warren Buffet, who give between 2% to 3% of their net worth each year to charity? Or is giving a mindset that is available for anyone, even at a fraction of a percentage of our income?

I accept that there are some people who are focused solely on survival. How many are in that state because so many others are focused on increasing their profit at the expense of others?

I see this as the humanity challenge, to be conscious of where we focus our attention, including what we are spending our money on. Imagine getting together with friends to intentionally ask how we could spend our money to make a difference in our immediate community or towards a wider global cause. What if everyone stopped for 15 minutes and had that conversation with their immediate circle of friends and committed to even 1% of their pay check for a month? What difference could that make?

This is an idealistic and perhaps unrealistic request (although there is a website for a 1% collective). The more likely option is highlighted by Thomas Piketty in his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, in which he reviewed centuries of data across 30 countries and made the case against wealth inequality. The solution he proposes is not for a personal change in priorities as I describe here. Rather, he calls for an increase in tax on the wealthy.

To me, this says that a concern for others outside of ourselves must be mandated. We cannot rely on human nature to address embedded inequality created by human nature. The proposed mechanism for this correction is a tax system that acts as legislated charity, which in itself is flawed by the politics of personal interest.

I do not expect to change the system in the time I have left on the planet, but I can change myself and influence those around me. With that in mind, I invite you to consider a group of people you could have a 15-minute conversation with and collectively ask the question:

If we were to make a difference in some way this month with 1% of our collective salary or time, what would that be?

If you do ask the question, I would be interested in hearing what you came up with in the comments below. If you feel there are others who might also benefit from the exercise, please share through the social channel of your choice.