Innovation adoption and beliefs that hold us back

My international travel is infrequent enough to keep it interesting. My journey through customs is a process of discovery as I re-learn what is expected of me. The departure card is one of the less memorable steps in this process.

I descended the stairs into the airport customs area to meet a crowd of people standing in a row filling out departure cards. Taking my place in line with the others, I picked up a pen to share in the experience.

My thoughts immediately turned to feeling sorry for whoever had to read my writing. “Surely”, I thought, “there must be a better way to do this in our advanced technological state.” Almost on cue, I heard a man’s calm voice off to my left asking:

“Did you know that you can complete your departure card electronically in less than a minute?”

I looked to my left to see a large, metal kiosk, which I assumed contained the man who asked the question. I was early for my flight and curious, so I completed my hand-written departure card and stepped over to see if I might take the man in the box up on his offer.

Looking at the screen, I read something about needing to use my QR code. To get this QR code, I needed to download the Brisbane Airport app on my phone, find the departure card section in the app menu, and complete the steps for filling out the electronic departure card. Having navigated myself through the process, I showed the kiosk the resulting QR code and the kiosk printed a departure card for me to sign.

Need more pens!

Out of curiosity, I waited around to see if anyone else used the kiosk. As I stood there, one woman looked back and forth from me to the kiosk and asked “What’s that? Do we need to use that as well as completing the paper form?”

“No” I replied. “I believe it is a new way so you don’t have to fill out a paper pass.”

The woman said “Oh, I guess that is what we will be using in a year.” And with that, she left with her handwritten form in hand.

Over the next several minutes, the crowd of people grew, and no one approached the box. I also did not hear the box repeat its promotion to save people time. As a result of a pens shortage and the number of people passing through, I did see people at the bench have to wait to complete their forms. Someone had even written in marker on the counter: “Need more pens!”

Like the misquoted Henry Ford bemusing about people who had no concept of cars wanting faster horses, travellers will want more of what they are comfortable with even if it is less efficient. The analogy that comes to mind is that of an acorn dreaming about what it will be when it grows up to be a bigger acorn. The acorn’s future plans will be defined by the constraints of its shell, with no concept of what it means to be a tree.

Personality, planned thought, or a deeper belief?

Why are some people more likely to engage with new technologies and new ideas? Are some people just “wired” to be innovative based on their personality, is it a rational decision-making process that anyone can access, or is there something deeper?

Some research points to personality, finding that those who exhibit less dogmatic personality traits or measurable traits of openness are more creative, innovative, and adaptable to change. Such observations are understandably seen as “common sense”. Our personality forms the lens through which we see the world. It is a defence response that helps us navigate through life.

This defence mechanism responds to the world based on our beliefs. Researchers have spent a lot of time coming up with models to explain these beliefs and show why we do some behaviours and not others. A few years ago, I pulled together as many of these theories as I could find when I published my research into consumer behaviour in relation to environmental versus convenience purchasing decisions. The resulting diagram connected all the models and is complicated to say the least.

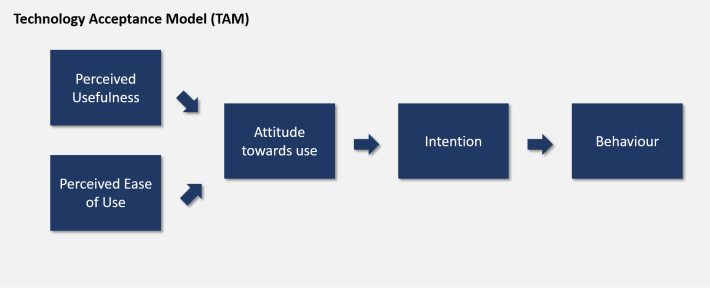

One model that simplifies why we engage in new technologies is the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). The TAM proposes that two beliefs we have about how useful something is and how easy it is to use will determine our attitude. Our attitude then determines our intent, and that intent drives our behaviour. If we want to change our behaviour, we simply increase our perception of how useful something is and its ease of use.

Using this model, you could say that my fellow travellers did not use the electronic departure card system because the perceived usefulness was not high enough. Even with a reduced supply of pens, people still waited for others to finish or borrowed additional pens from each other. Pens were more familiar, while the usefulness of the kiosk would be realised “perhaps in a year”.

Alternatively, you could say that we could increase the ease of use of the electronic departure card system through providing additional kiosks, adding more prominent calls to action, and clearer instructions. There is an education and a change process needed for any new technology that can be overlooked by those creating the technology.

I will declare that I have a significant advantage in my perceived ease of use. A few years back I was part of the team that developed the original Brisbane Airport iPhone application. Even though I was not involved in the development of the electronic departure card functionality, I was already familiar with where it might be in the app.

By comparison, a woman who sat next to me on the plane said she got frustrated and gave up when she mistakenly tried to scan the code on her boarding pass. This woman was flying back from having had received a medal in a professional golf tournament, and was returning to her role as a senior project manager in the finance sector. You could say that not being able to use technology that was supposed to be easy was a threat to her views of being competent and capable. If we have a perspective that something must be negative, it is often easier to view technology as deficient rather than ourselves as incompetent.

The thought of adjusting the two variables of usefulness and ease of use appears very rational and logical. Except much of our behaviour is often neither reasonable nor planned, but based on a deeper belief about how we see the world.

Is the world a safe place?

“What you focus on, you create”

Like the previously mentioned acorn analogy, some people see life through their current constraints, while others see life through possibilities.

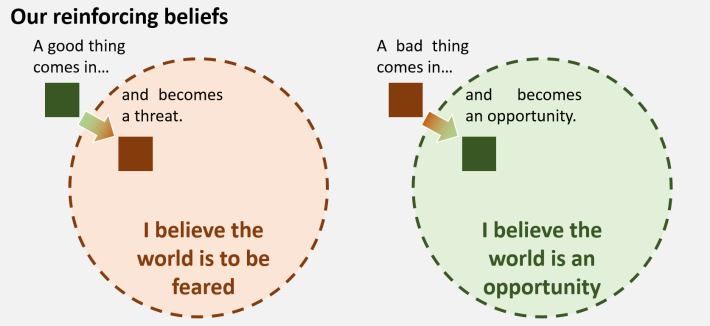

Some people see the world as something to be feared. Resources are scarce and need to be protected. Change is a threat to be avoided or attacked. If something good comes along, it is to be questioned with suspicion, and possibly interpreted as a danger to the security of status quo. Someone approaches you, smiles, and reaches out to shake your hand, and you question their agenda and wonder what they want from you.

Other people see the world as an opportunity to be explored. Resources are abundant and are to be shared. Change represents a potential to be taken advantage of. If something bad comes along, it can be reframed and treated as an opportunity. Someone approaches you, smiles, and reaches out to shake your hand, and you start thinking about how you can help them or get to know them.

This is not to say that bad things do not happen, any more than everything that happens is good for us. Life holds tragedy and there are those who inherently want to harm others. However, many outcomes are created solely from our expectations.

We see this when we work with others in what is referred to as the Pygmalion Effect, where our perception of someone else’s performance is a significant factor in defining that performance. That same principle applied to ourselves is called self-efficacy, or our belief that we can succeed.

Our belief about the threat of the world and our ability to navigate that threat is the fuel that drives our personality to defend us in predictable ways. This defence position is often not triggered by actual threat, as society has evolved beyond the simple question of “What if I die?”. Rather, the question heard by our different personality types is perceived as:

- What if I do not get it right?

- What if they don’t like me?

- What if I am not successful?

- What if I look stupid?

- What if I have to work harder?

- What if I am embarrassed?

These questions can seem like they are keeping us safe, but can also create barriers to trying new things. The reality is that trying new things is very likely to result in any of the above questions becoming a reality. And that is OK. Because you are OK.

How do you see the world?

“The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The next best time is today”

The rapid pace of technology change can both inspire and produce fear. The number of people being disrupted is proportionately larger than those who are disrupting. Many people are facing threats to security and identity, perspectives that can limit sustainable creative thinking and acceptance of innovation.

Our beliefs are formed when we are young, and we are often not conscious of how those beliefs guide our behaviour. Our best hope for substantial change is through developing values and entrepreneurship in young people, so they can experience success and failure in an environment that teaches them early that both are OK.

For those of us with embedded beliefs about the world, we are facing an unprecedented combination of complex challenges and significant opportunities. We need to challenge our beliefs and move from acorns asking for more pens to consider the possibility of what it means to be the oak tree.

Love the article Chad!

“If we have a perspective that something must be negative, it is often easier to view technology as deficient rather than ourselves as incompetent.” I don’t think that there is anything wrong with that. Everyone got his strengths and weaknesses. Let’s take your example of the woman using the departure card kiosk trying to scan her boarding pass instead of an app generated QR code.

One could blame her (and many many others) on not properly reading the instructions. But why not blaming the UI of the machine? Why doesn’t the machine inform the departing passenger about how to make use of the kiosk once it has detected that a PDF417 (code on the boarding pass) was scanned? And why not allowing the scan of boarding passes and passports in general? 80%-90% of relevant information can be captured from those documents? And … why the app?! 🙂

Because business decisions drive technological outcome. Even though the technology is there to improve ‘ease of use’ and to increase ‘perceived usefulness’ it may not be in line with the business agenda.

Keep up the inspirational work! And maybe you could provide an RSS feed?

Thanks,

Stephan