Five observations for regional innovation hubs from a North American Innovation Tour

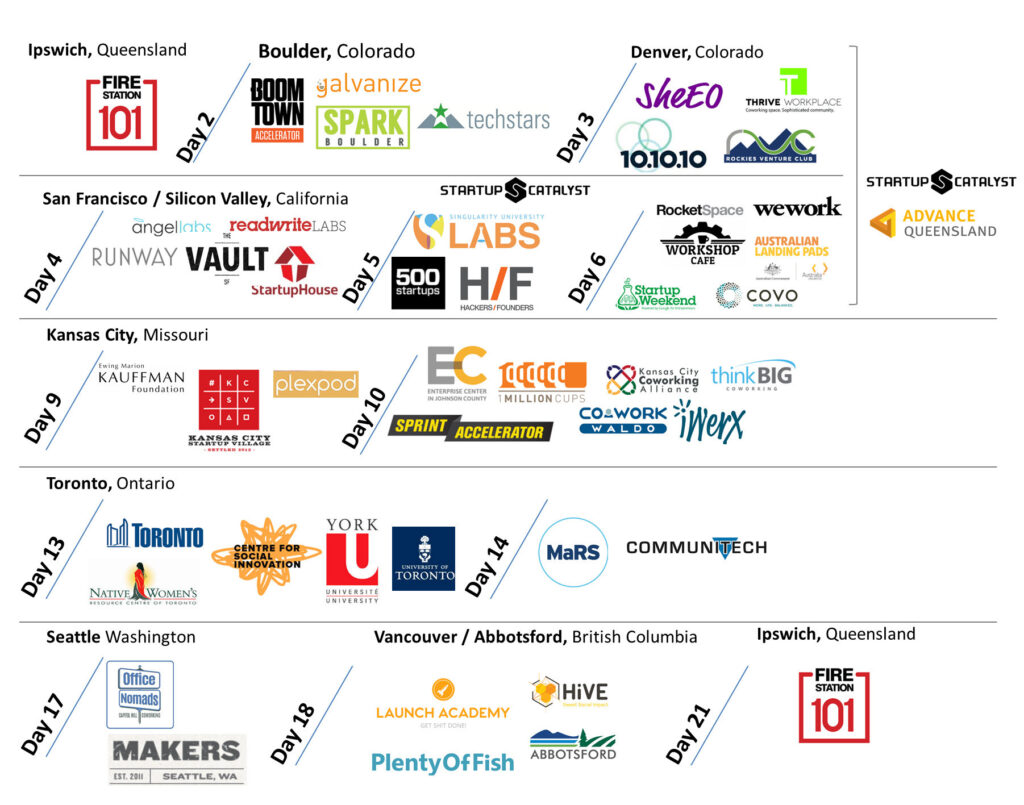

It has been a busy few months since my three weeks in North America visiting as many innovation hubs, co-working spaces, investment groups, councils, and accelerators as I could fit in across Boulder, Denver, San Francisco, Kansas City, Toronto, Seattle, and Vancouver. Many thanks to the Startup Catalyst program for organising the first week as part of a group of other Australian innovation leaders and Advance Queensland for sponsoring a portion of the trip for myself and others in the cohort. I am also incredibly grateful to all the people I met on the journey who volunteered their time and information.

I returned with all intentions to capture and share lessons learned in assorted blog posts. I got as far as consolidating my videos into a series of video blogs which you can peruse in my YouTube playlist. With a long weekend ahead of me and as a pause from pumping out a recent grant application, I figure now is a good a time as any to reflect on a few of the conversations I hear myself having around topics including:

- The need for specialisation in regional hubs

- Revenue streams available for innovation hubs

- The role of local government in applying innovation to community challenges

- Time frames and ecosystems required for regional innovation transformation

- Resourcing required for different innovation hub business models

A note on terms and context

Context

For context, my perspective is based on my research into the role of physical innovation hubs in building resilience in regional communities, and strategies as we head into year two of Fire Station 101, a local-government backed innovation hub in Ipswich, Queensland.

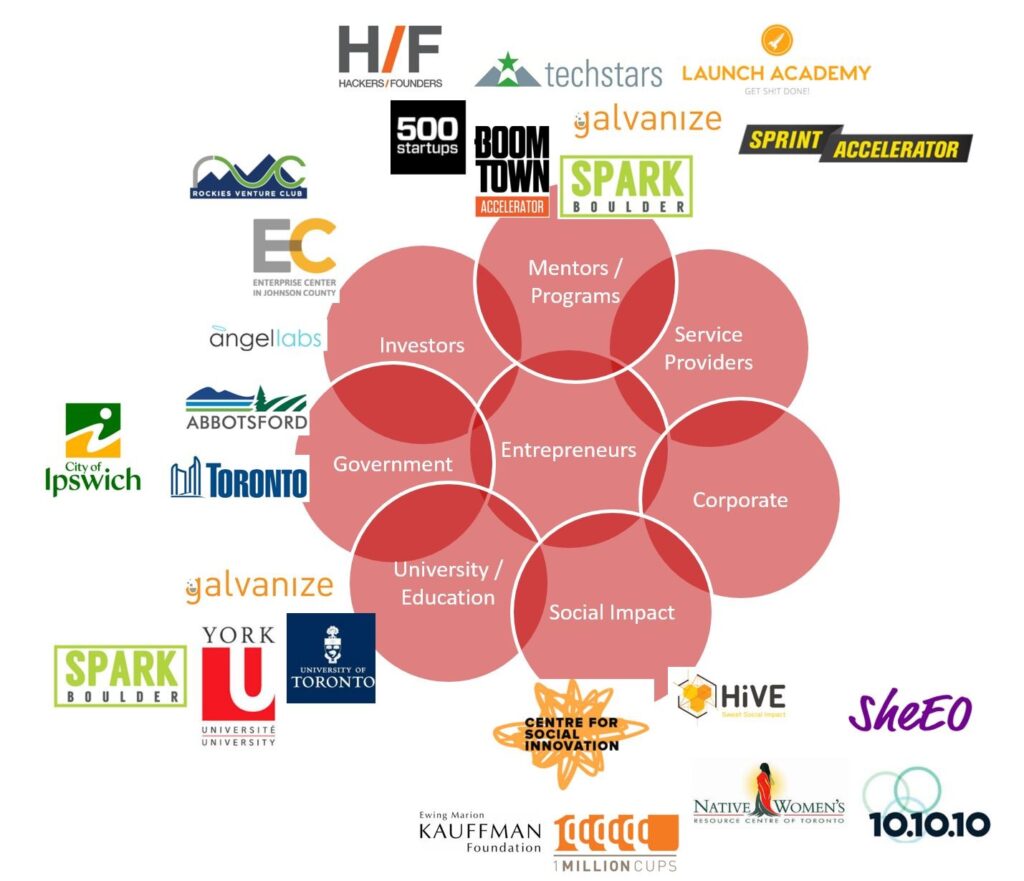

Ecosystem

The ecosystem includes the different actors involved in the entrepreneurs journey. You can slice this a number of ways and I gave it a crack back in 2015 when I wrote about the open innovation ecosystem. The lines between functions are fluid where accelerator programs act as investors and corporations, governments, and universities develop accelerator programs, offer legal and accounting services from internal departments, and act as first customers.

There is an ongoing academic and commercial body of work to define and and measure ecosystems and identify how best to facilitate an entrepreneur’s success in a given region. What is generally agreed is the need for the entrepreneur to be at the centre of the efforts, affectionately known as #FounderFirst.

Co-working, Innovation hub, Accelerator

Spaces act as a means to bring these ecosystems together through intentional events and programs as well as ad hoc collaborations and connections.

The emphasis of a co-working space is often on the amenities and maximising return per square metre of real estate. This can dictate who is attracted to the space and where investment is made. Some of the spaces I visited on my trip shared that they de-emphasised a focus on startups in favor of more established and reliable businesses.

An innovation hub by comparison has an emphasis on attracting startups and businesses aligned with a defined mandate. This focus comes with dedicated resources towards programs and community-building activities. In addition to measurement of members per square metre, an innovation hub will also be measured on results achieved by members.

An accelerator is a curriculum delivered in an innovation hub or co-working space designed to help a business grow and scale. Some accelerators are synonymous with the space in which they operate but most of the businesses in the space are current or alumni participants in the resident program. Other terms include incubator and pre-accelerator based on where the program is positioned in the life cycle of the business.

Five observations from the innovation tour

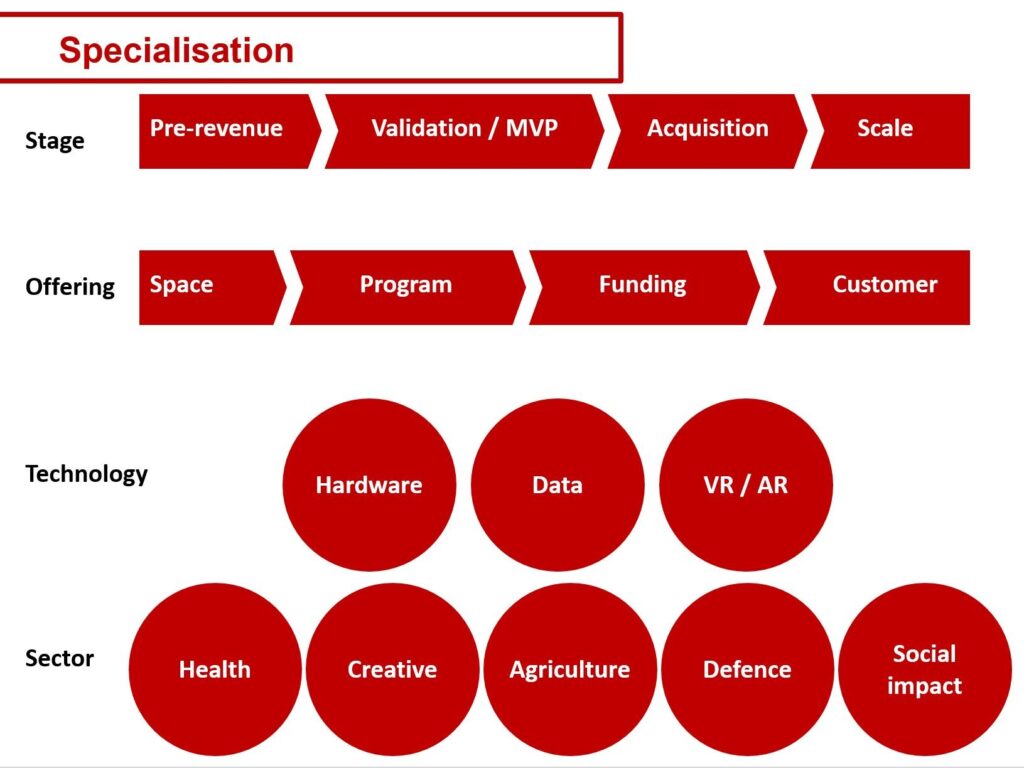

Observation #1: A need for specialisation

Ecosystems such as Boulder and San Francisco are mature with a wide variety of programs, groups, and spaces servicing a range of needs. The number of players means each needs to know where they fit and how they collaborate or compete with others in the local and wider market.

I observed four areas where there was specialised focus. First was in programs that focused on the stage of the business, ranging from initial untested idea to wider market scale. Startups in spaces who were expanding globally shared how they wanted to bounce ideas off other entrepreneurs with similar challenges as compared to those going through their first business model canvas or being introduced to the Lean Startup approach.

Second was in the offering of a single focus or combination of offerings in the one business, be it just a space, delivering in-house programs, developing an attached investment fund, and/or acting as the first customer. Some spaces championed having everything under one roof, while others emphasised a niche focus on one aspect of the journey.

A third area of focus is by technology. The ReadWrite labs accelerator is for hardware-focused startups for any industry and HTC’s ViveX accelerator has an emphasis on virtual reality.

Finally, many programs and spaces are dedicated to a given sector, be it health, creative industries, or social impact. Programs and spaces such as TechStars, MaRS, and 500 Startups also create versions of their offerings dedicated for the sectors as the programs mature and expand.

Through my trip, I pondered the question about which came first.

Does the ecosystem mature as a result of specialisation, or is a mature ecosystem required for there to be specialisation?

To hedge the bets, we can focus on both building the ecosystem and identifying key areas to specialise.

Observation #2: Revenue streams available for innovation hubs

Innovation hubs require multiple revenue streams to be sustainable. The value proposition and customer base is different to a straight co-working space. A stand alone seat for hire model is not sufficient to support the additional programming and community support that goes with investing in startups, who often do not have the revenue streams available to pay for higher desk rental. This is particularly the case in regional areas that have more early stage startups.

Revenue streams I experienced on the tour include:

Revenue stream 1: Co-working space / venue hire

Conference room at Plexpod in Kansas City

A straight space rental model, from desk or office hire to use of the space by the public. One hub rented a main area to a church on Sundays and another used the main area for conferences. Fire Station 101 lets external organisations use the space as a venue where the event aligns with our core mandate of driving innovation in the region. We also need to balance revenue from venue hire against keeping the space free for members and are not in the business of competing directly with other venue spaces.

Revenue stream 2: Finding new technology for corporations

Runway in San Francisco, finding new technologies for corporate innovation

Corporations pay the hub to find new technologies related to their business. This is a combination of engaging in external market scans as well as having the programs that attract the technologies and startups to the hub. This requires dedicated and specialist resources similar to a consultancy model.

Revenue stream 3: Training

Training delivered at iWerx in Kansas City

The hub delivers training programs on a fee for service basis on relevant topics such as digital technology or innovation thinking. The approach can supplement rather than compete with existing training providers and educational institutions, with the hub acting as a catalyst for building capability and capacity in regional areas.

Revenue stream 4: Accommodation

One of the startup houses in the Kansas City Startup Village

Startup House in San Francisco

Two examples of accommodation I saw were Startup House in San Francisco and the Kansas City Startup Village. Startup House had a second floor that felt very much like a backpackers and KC Startup Village offered AirBNB-style accommodation.

In considering ways to make it easier for startups in regional areas, I considered whether a space acts as a launchpad or a pillow. Making it too easy for the startup without corresponding achievement goals or programs may mean they do not have the pressure to kill an idea or pivot if it is not working. In discussing this with leaders in the ecosystem when I returned, someone shared about overseas startup programs where founders are boarded in very small rooms with many others, but provided with exceptional labs and working spaces to encourage more time in the hub and less time at home.

Revenue stream 5: Program sponsorship

Google partnership with Communitech in Waterloo, Ontario

Programming such as accelerators or support for startups requires resources. Sponsorship by a corporation or government can help fund delivery of specific outcomes from the program. Sponsorship is often in the form of an ongoing corporate partnership program, one-off events, or direct support for one or more startups or entrepreneur members.

Revenue stream 6: Consultancy

Think Big in Kansas City delivering a Global City Teams Challenge Smart City Supercluster Workshop

Consulting to corporations and industry sectors is a logical next step for hubs that have the capability to deliver weekend hackathons and support a diverse range of startups. Executive innovation workshops, internal corporate hackathons, and industry cluster collaborative sessions can all generate revenue with a specialist innovation focus. These services come at a premium that is typically the domain of larger consultancies such as PwC, Deloitte, and Accenture.

Hybrid models that partner with established consultancies can support regional hubs that may not have in-house capability. Ideally, the hub builds sustainable capability so the long-term value does not go entirely to the external consultancy.

Revenue stream 7: Equity / Venture Capital

Boom Town accelerator in Boulder, Colorado

Most accelerator programs have a fund to invest in startups for equity. This equity may be converted to revenue at a sale or other liquidation event.

This is a long-play, high-risk revenue stream typically reserved for the external investment fund or accelerator program. The hub does not benefit unless the hub is actively involved in securing the investment or the investor owns the hub.

The emerging model in the market as mature accelerators look to scale to new markets is that the hub pays for an external accelerator program to run in their space. The accelerator takes the equity in the participants in addition to the fee for service to deliver the program. A challenge with this model is that the hub needs to secure sponsorship to run the accelerator or find another way to fund the program and does not have the benefit of retaining equity in the participants who go through the program in the hub.

#3: Role of local government

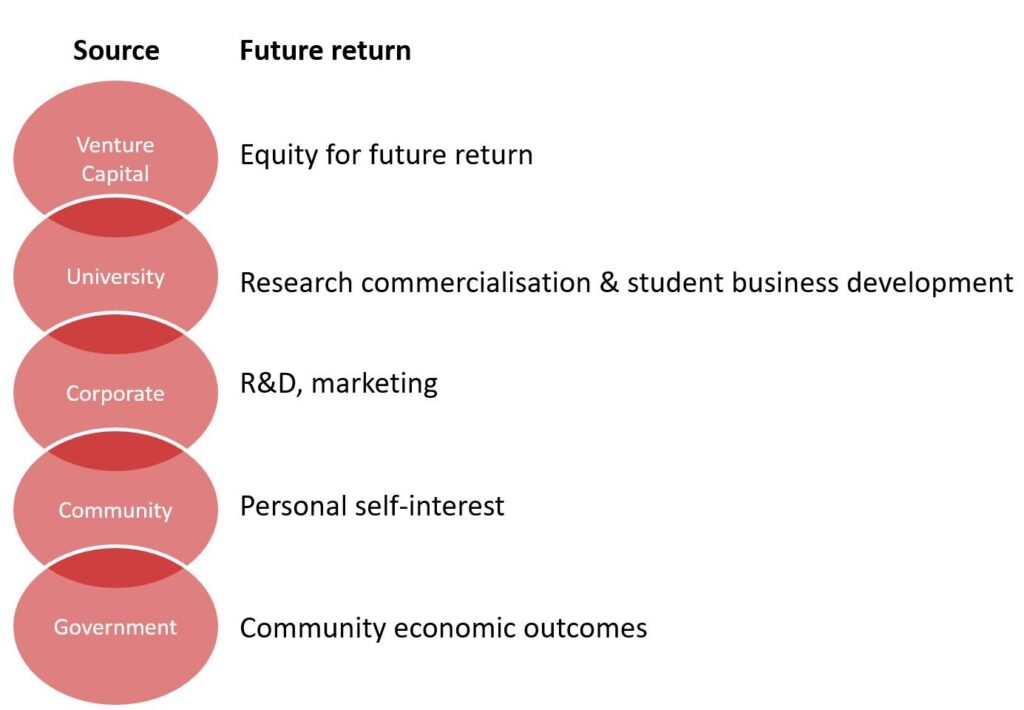

I frame innovation hubs as operating in one of five business models based on the source of primary funding. The source of funding often dictates the types of members in the hub and the outcomes of the hub.

- Venture Capital: Supporting the hub for future return on investment from startup members. Startups are usually accepted based on the assessment of future value from a sale, mandating that founders are looking to exit from their business.

- University: Supporting the hub to commercialise research and attract new students. These models are evolving. The B.E.S.T. hub I visited at York University focused on the startups success, using university courses to build fonder capability and make global connections.

- Corporate: Supporting the hub for research and development, access to technology and idea commercialisation, community engagement, and market share.

- Community: Usually an individual, either independently wealthy or with a passion for community development, supporting the hub out of personal passion and self-interest.

- Government: Supporting the hub for community economic outcomes.

I tested this framework as I visited each of the locations on my tour with a particular frame of reference from managing an innovation hub fully owned and operated by a local council.

Out of all the models, government, and in particular local government, is most incentivised to look after people right outside the door. We can have multi-million dollar conversation in an innovation hub, and encounter community challenges in the streets as we leave the building. Many of the locations I visited made reference to the growing inequality gap, and the term “gentrification” was used a few times.

Emerging social impact models such as Impact Hub, Centre for Social Innovation, and The Hive in Vancouver look to close this gap. The Kauffman Foundation in Kansas City is a leader in social entrepreneurship and ecosystem measurement. Other forms exist where corporations sponsor social impact programs such as the Random Hacks of Kindness or Techfugees hackathon programs.

Innovation on topic with the City of Abbotsford and Province of British Columbia

While these models and programs might pursue local government for funding, I am looking for models where local government is intentionally investing in innovation hubs as the primary agent to deliver local economic outcomes with a social focus. Two local governments I spoke to in Abbotsford, British Columbia and Toronto, Ontario were both pursuing these approaches.

#4: Time frames and ecosystems required

MaRS Discovery District in Toronto

Building an ecosystem just takes time. It can be easy to fall into the trap of comparison when visiting mature models like MaRS Discovery District in Toronto or some of the places in Silicon Valley or Boulder, Colorado. I had to keep reminding myself that Fire Station 101 has been in operation in Ipswich for only 12 months While I am doing what I can to learn from more mature models to expedite our outcomes, sometimes you just have to put in the time.

Understanding time frames is important to manage expectations. The temptation can be to look at one aspect of investment, be it a physical space or infrastructure, and wonder why you are not “the next silicon valley” as a recent Bloomberg article positioned itself when looking at Google Fibre and Kansas City.

A successful ecosystem requires all aspects to develop. Some places I visited had long-standing spaces but struggled to mobilise their local angel investors. Other places had mature entrepreneur pathways but limited university connection. In Ipswich, one of the challenges is feeling stretched to manage a physical member-based institution while also developing university connections, building entrepreneur and technical talent pipelines, and supporting local investor efforts. Each of these facets were self-sustaining in mature communities.

#5: Resourcing required

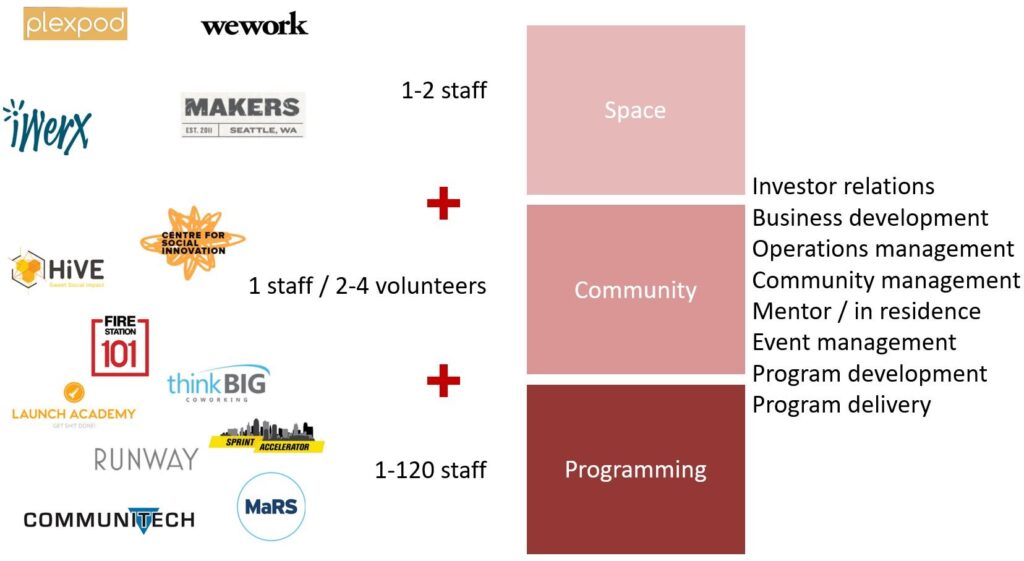

Which leads me into considering the resourcing required to deliver outcomes in an innovation hub. If you are just managing a physical space, you can get away with one or two staff. As you move into community management, you need additional resources and can often leverage volunteers through benefits such as free membership programs.

Once you start intentionally supporting startups or social outcomes through programming, you need dedicated resources. I asked places how many staff they had, and responses ranged from 2 to 3 up to 120 to 160.

Functions where resources were committed include:

- Investor relations: Managing communication back to existing investors, including annual reports, board meetings, and highlighting new investment opportunities.

- Business development: Securing new sponsorship, corporate partnerships, member revenue, and market share.

- Operations management: Managing the day to day operations of the hub, including space management.

- Community management: Building the culture and bringing the internal and external community together.

- Mentor in residence: Actively supporting members to build, grow, and scale their businesses.

- Event management: Identifying new events and speakers, managing the schedule, and coordinating event delivery.

- Program development: Developing in-house programs, products, and service offerings for members and sponsors.

- Program delivery: Delivering programs, both in-house and external.

Many regional spaces are delivering all the functions with one or two individuals, often volunteers. It is important to understand resourcing required for innovation outcomes as we see more and more spaces pop up in response to a growing innovation narrative. Resourcing models include developing in-house, acquiring through recruitment, and outsourcing to a co-working or accelerator brand.

A successful innovation hub model is dependent on getting the resourcing model right aligned with the local ecosystem. Investment needs to be secured for resources in the right areas to generate sustainable revenue and outcomes desired by the funding source.

What’s next

The trip was incredibly valuable to gain insights into different models and hear wisdom from others who have been in the game for so long. Focus areas for a space heading into its second year include a need to:

- Specialise in specific sectors and startup stage;

- Establish structure around programs and additional revenue streams;

- Leverage local council’s role by emphasising community outcomes; and

- Define and invest in the resourcing required to achieve outcomes now and into the future.

All of this is in the context of a Founder First approach.

My hope is that this post adds value to others in conversations about developing regional innovation spaces. I welcome other perspectives to add to the conversation and more rapidly advance the innovation journey for entrepreneurs in regions across Australia and globally.