The Australian innovation ecosystem – from 1788

What was the first Australian innovation ecosystem after settlement?

In developing background information for my thesis, I briefly explored the first instance of each actor in the Australian system of innovation. What was the first government, education, research, technology, financial capital, entrepreneur, and other roles that emerged after settlement into a working system for new ways of operating?

The process has been a great history lesson. I have been in Australia for 20 years, and an Australian citizen for many of those. Yet I have had only a working knowledge of the progression of society from settlement in 1788 New South Wales.

I also acknowledge the indigenous culture and peoples who were here prior to settlement and the significant culture, innovation, and technology that was lost when the land was occupied. Pascoe’s Dark Emu book provides a good overview of the pre-settlement innovations. Boyd Hunter also provides a good overview in The Aboriginal legacy chapter in 2014’s Cambridge Economic History of Australia.

The main intent and focus for my research is on the relationships and functions of the contemporary system of government, universities, investment, entrepreneurs, and other roles supporting innovation activity.

Actors in the post-settlement Australian innovation system

These are just a few of the examples, not intended to be comprehensive or even the actual first – simply the first that I found with a cursory glance through literature. This is as sample for brevity in this 30-minute post:

Entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurs were at the centre of 1788 New South Wales system of innovation, as entrepreneurial settlers adapted for survival and establishment of a new land. The immigrant ‘farmers” came with little to no experience. As noted in 1826 by Atkinson :

“There was at first great deficiency of agricultural knowledge and rural experience, but if they knew little practically of farming, they had at least the advantage of having nothing to unlearn. Considering that a large part of the agriculturists in New South Wales were originally officers in the army and navy, or young men from school and college, or inhabitants of great towns, their success is quite extraordinary.”

Mining and minerals also benefited from the entrepreneurial drive, inherent to the first coal mine shortly after settlement in New South Wales. The controlling structures, legal frameworks, and technologies of the early mines were largely carried over from England but not sufficient for the local environmental or social context.

The discovery of gold and subsequent rush in the 1850s resulted in rapid growth as mining came to represent 35 percent of GDP, increasing the Australian population three-fold, and growing wages in Victoria by 250 percent. Similar to agriculture, pressures from speed of growth and scarce capital naturally resulted in rapid adaptation of external technologies and management practices.

Government, Industry associations and Peak bodies

We also see early roles of government and entrepreneurial policy. Local government was created with the establishment of the initial five Australian colonies and accompanying political and economic institutions. The rapid minerals growth highlighted tensions between entrepreneurial miners and the newly formed governments over company structures that were conducive to high-growth and high-risk ventures.

Policies such as the no-liability company act of 1871 which allowed faster company registration with lower capital was a result of newly formed business advocacy groups successfully lobbying the government for entrepreneur-friendly policies. We can see parallels today as advocacy groups lobby for changes to bankruptcy laws and company structures.

University

Talent and education are another critical aspect of the innovation system. Early rapid growth required development of local skills and new education institutions formed to meet the need. Sydney University was the first Australian university in 1850 followed quickly by the University of Melbourne in 1853. Other states followed suit and by 1911 each state had its own university. Here again we see the entrepreneurial approach similar to what was evident in early farmers and miners:

“Not many of Australia’s institutional founders were ‘experts’ in university planning, which probably helped them in their innovation. Most of those instrumental in setting up the University of Queensland, for example, had never set foot in a university, leaving them free to think through what they needed unhampered by nostalgia.” (Forsyth, 2014, p12).

Tafe and trade school

Alternatives forms of education to universities also became available to meet the increasing demand for technical skills, such as the Mechanics’ Institute established in Hobart in 1827 and the Sydney Mechanics’ School of Arts in 1833.

Industry and technical communities

They even had pre-1900 meetups. Just as innovators of today congregate at innovation hubs and find each other on meetup.com, early entrepreneurs, policy makers, investors, and technologists bumped into each at the local groups of the Agriculture and Horticultural Society of New South Wales (1826-36) and the Australian Society to promote the growth and consumption of Colonial Produce and Manufactures (1830-36) (Inkster, 1985). In Forsyth’s review of early emergence of Australian education, she describes a situation where:

“Few of the thousands who rushed to the gold fields in the 1850s had much knowledge of mining techniques. At the Sydney Museum of Practical Geology, people attended lectures on these basic topics before heading west to Lambing Flast and Hill End.” (Forsyth, 2014, p14).

Research

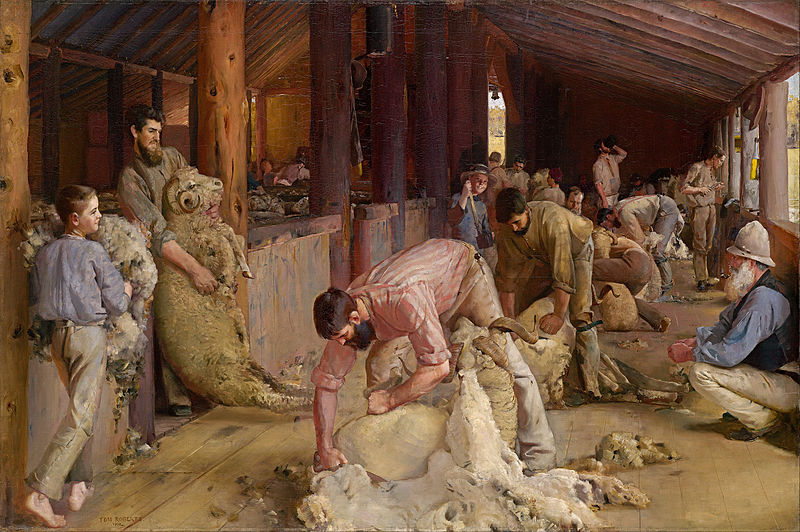

The national investment into innovation research came about shortly after Federation (1901) with the federal government’s establishment of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) in 1926, later becoming the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in 1949. By 1950, CSIRO employed over 3,000 staff and accounted for over half of Australia’s national research spend. A significant focus of this research was on primary industries, which made up over 80% of total Australian exports in the 1950s. Funding from the wool industry alone made up 15 to 20 percent of CSIRO’s total budget in the 1950s and 1960s (Upstill, 2019), building on its legacy as a primary export from the 1820s (McLean, 2013).

Finding what is new under the Australian innovation sun

As we race headlong into the future, if can feel academic to slow down and review the past. And yet if we have the view that we are doing what no one else has done before, we risk using new technology to recreate the problems of the past faster with greater impact. We also risk alienating those who have experienced the past cycles and can provide valuable insights to avoid a few mistakes along the way.

Just because we give a name to something such as “innovation ecosystem” or “startup” does not mean it did not already exist. Australian entrepreneurs have been doing startups within an innovation system for centuries.

In reviewing Australia’s first innovation system: entrepreneurs needed to be central; tension existed between industry and government struggling with rapid change; many of the support actors were startups in themselves; everyone was learning on the job; universities were critical for technical skills but were slow to adapt to rapid technology change; and the system adapted – albeit slower than desired – to meet the needs of the market.

Sounds similar to today.

One thing I did find constant in literature was a criticism related to commercialisation and collaboration in Australia. Policies, technology, and actors change. People are a constant and culture is pervasive. Regardless of roles, a need for collaboration among diverse roles in the innovation system is critical for success.