New Year’s silence: 6 days and 60 hours of meditation using Muse

First, a confession: this post started as “Insights from a self-managed 10-day Vipassana silent meditation retreat”. Below I share the background, capture my reflections, identify shifts in perspective, and consider insights for the year forward.

I share so others who may be in a similar situation may take value. I also share so that those who have been on a similar journey might compare and share their insights.

A self-managed retreat

I had heard about 10-day Vipassana retreats in passing from friends and colleagues.

Before 2020, the idea of spending 10 days in silent focus sounded interesting. Towards the end of 2020, it seemed a necessity.

Around October, I started looking into the course with greater intention. There are a few locations that provide the full 10-day program, with the closest being a couple of hours away from me on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast. The schedule showed a course starting on 26 December. I figured that the end of year period would be a good time for a pause. Apparently, so did several other people.

The day the applications opened in November found me hitting refresh on the website every 30-seconds like I was buying tickets to Coachella. At 1:03, the “Apply” button became available and I completed the online form. By 1:15, all spaces were filled and applications were closed. I received an email a couple weeks later that I was on the waiting list.

So with no other options for a structured 10-day program and no other apparent 10-day windows in my 2021 schedule, I explored how I might be able to do a 10-day meditation course on my own. The ten days are completely silent with no interaction. The daily instructions are pre-recorded and interaction with the instructors is optional if you have questions. In hearing from others who had completed the course, the instructors usually point you back to continuing the practice rather than offering a solution. I figured if it is pre-recorded and no contact, why not try it on my own?

I searched Airbnb for a suitable location. I googled “Vipassana coaches” to find people I could speak with to better understand the process. I read a multitude of blog posts by others who had been on a course. I spoke with friends who had completed the course.

As I planned out my experience, I noted that a self-managed course might have unique outcomes while also missing out on benefits. In my conversations with coaches and past participants, I asked what I might do to compensate for what I might miss from the regular course. It was recommended I be mindful while preparing food and keep the preparation simple, as I would not have the benefit of someone preparing it for me. Another person mentioned having an instructor on call through the course. For accountability, I planned to use the Muse headband to track my progress. I would, however, miss out on the communal experience of sharing with others at the end of the program, not experience the temptation of interacting with others, and not have the watchful eye of the instructors keeping me on track.

At the end of my review, I did not find anything that pointed to it being unhelpful, much less a negative experience or waste of time.

With support and insights from friends, colleagues, and coaches, I put the plan in motion.

The path to a 10-day

Subjecting yourself to 10-days of self-isolation in the midst of a pandemic may sound redundant. I did not head into the decision lightly, although I admit to questioning my choice a few days before I left. Ten days is a long time when considering what else can be done, such as spending time with family and friends, completing reports, working on research papers, developing new products and programs, or binging any number of video streaming services. I also felt somewhat selfish and entitled taking ten days out for myself especially at the end of the year.

I reminded myself that my attachment to the size and magnitude of the to-do list was one of the reasons I felt the need for the ten days. Gaining focus would help everyone in the long run.

The end of 2020 came as a transition for me. I submitted my PhD thesis even as work in other areas of my life increased. Along with the thesis, I had developed an online community of over 1,000 leaders in Australian innovation and entrepreneurship, contributed to a number of mapping and measurement projects, taken Research Fellow positions with two universities, facilitated and spoke at a number of events including the G20 Roundtable on Entrepreneurship, coached community leaders as we developed new collaborative approaches for economic and community development, and travelled in regions continuing and applying my research.

And yet as more opportunities emerged, my productivity declined. I became distracted and unfocused.

Everything felt like walking, talking, and typing through molasses.

This is particularly confronting in the field of innovation and entrepreneurship where the twitter-elite manage to “crush their goals” at “100 per cent” to solve the world’s greatest challenges while maintaining work-life balance. The sector is built on a premise of learning from failure, although lessons are usually provided as poignant anecdotes by those on the other side of success.

I became increasingly concerned watching my attention span shrink as my task list grew. At 48, I reminded myself that I had over the years grown companies and communities. Pull my string and I utter Buzz Lightyear Entrepreneur phrases like “Extra-ordinary outcomes require extra-ordinary effort”, “When you do what you love it is never work”, and “Past success predicts future outcomes”. Perhaps it was the wear and tear of 2020, the culmination of personal and professional changes, or some shift in a mental model. My mojo was missing-in-action.

There are certainly a number of prescriptions available for this malaise. I knew enough to have “physician, heal thyself” included in my personal narrative. Indeed, I had consumed, prescribed, and delivered many options, including programs, productivity hacks, books, seminars, fitness regimes, professional support services, and spending days on the beach scrolling Instagram motivational memes. Each works to varying degrees.

As a centuries-old approach with proven psychological underpinnings, meditation is a top option for long-term mental performance.

My exposure to mindfulness and meditation goes back a few years. Some examples include: a Master of Applied Psychology which includes coaching, mindfulness, meditation, and psychology; formal training frameworks as a leadership and development consultant; a six-month internship with the Enneagram personality framework with half-hour daily meditation and 4-hour stints on weekend retreats; facilitating guided meditations in one-on-one individual coaching sessions and group facilitation workshops, and integrating frameworks of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) into my personal and coaching practices.

All that to say while I have enough exposure to be familiar with the practice of meditation, I do not consider myself an expert by any means. I went into this new process as a learner.

Views on Meditation and the Vipassana program

I approach meditation largely from a psychological perspective. I acknowledge that many people integrate a spiritual element as well. The Vipassana program is not contrary to any religion or spiritual belief system but asks that the practice not be mixed with any other system for the ten days. This is to avoid giving the mind an “easy out” by focusing on an external concept of a deity or scripture, creating a replacement with a new object of craving.

From a psychological perspective, the mind behaves in predictable ways according to evolutionary fight-or-flight responses. On autopilot, the mind clings to pleasure and avoids pain under the guise of our self-interest.

Meditation trains the mind to focus on a point in time, countering an automatic reaction.

A neutral point of focus is the breath. The breath is without judgement, always with us, common to everyone, and less likely to be open to interpretation and ego. By training the mind to focus on the breath consistently during meditation, you are less likely to unconsciously react when something unexpected happens when you are not meditating.

The 10-day Vipassana program walks participants through the process of first focusing on the breath over the first few days, then expanding the focus to different parts of the body from head to toe. The program is deceptive in its simplicity.

Our lives can be filled with constantly learning new things. Multitasking is celebrated. Audiobooks and YouTube videos are played at double speed. Micro-credentials allow us to learn five things at once. The world is moving to a Matrix-like input jack in the back of our head where we plug in and learn Kung-Fu in a matter of seconds.

Focusing on one thing, particularly something as simple as the breath, has become counter-cultural.

An underlying premise of the Vipassana program is that the only way we can really learn is through experience. We do not learn the benefits of meditation by reading a book or blog or by listening to a speaker. We learn by meditating. And meditating. And meditating some more. We cannot experience overcoming the suffering of tedium, a racing mind, and physical discomfort if we do not suffer these things and work through them. The Vipassana program is learning for ten hours a day across ten days.

The learning process involves experiencing the sensation, observing our reaction, adjusting, continuing, and repeating. It is a marathon of one step, repeated over an over to an indeterminant end point. The future and the past become irrelevant in a focus on the present state of the current breath. We learn through the culmination of observing our response to countless breaths.

The Muse mind-sensing headband

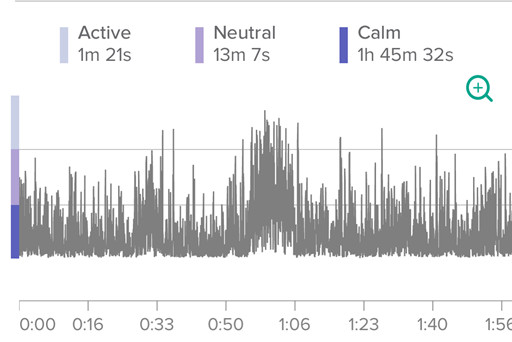

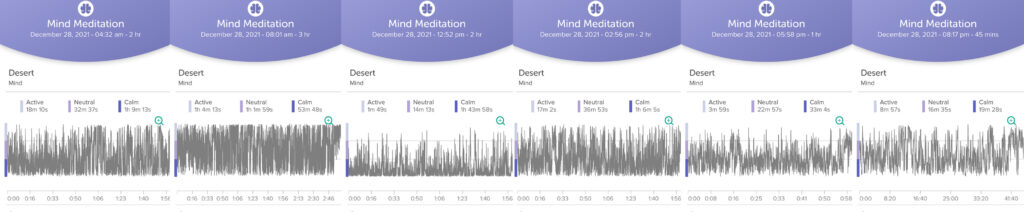

One of the aspects of doing a self-managed program is that I would be able to use the Muse meditation headband. This would understandably not be allowed in a regular course. My aim in using the headband was to provide some level of accountability, as well as a point of curiosity.

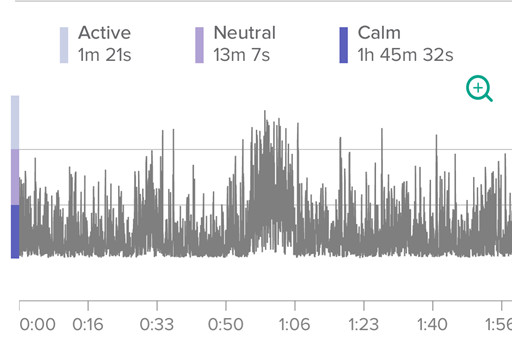

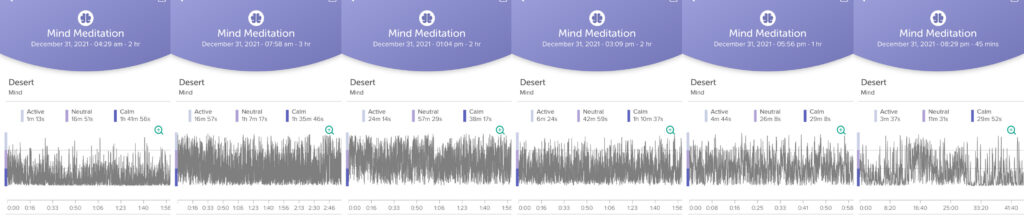

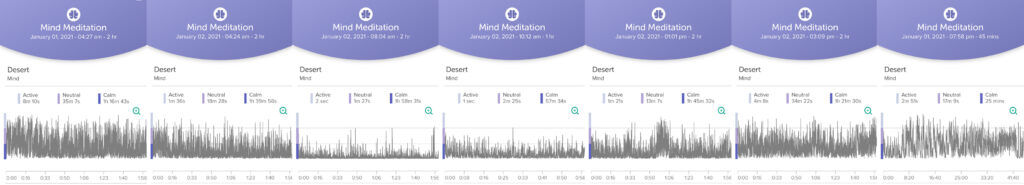

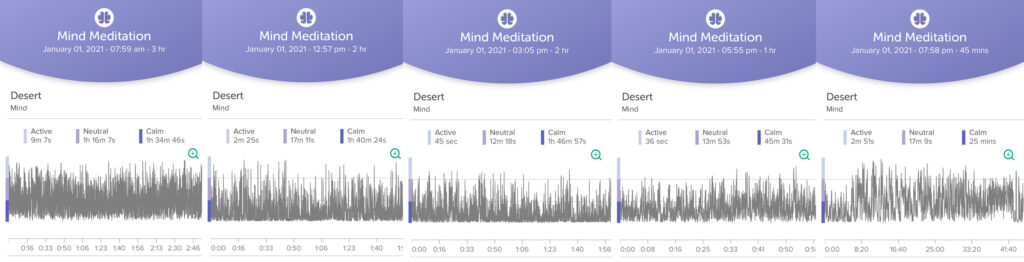

The Muse headband senses brain patterns. When meditating, it records whether you are in an active, neutral, or calm mental state, along with other aspects of your physiology. It also has features like increasing or decreasing background noise depending on your state, introducing the sounds of birds as a feedback mechanism during a calm state, and pre-recorded guided meditations. I had the sounds turned off for this experiment but have used them in the past.

I have been using the Muse headband on and off since around 2016. I used it more when I first got the device, prompted in part by the achievements and reward system that gave you levels based on certain meditation behaviour. Therein lies one of the challenges with Muse, or at least my challenge. It is a form of extrinsic validation that places judgement on the reward and results with the potential to encourage ego and attachment to performance. That said, it can be a great tool to get someone into the practice of meditation. It also provides tracking for more experienced practitioners and has an extensive library for those who appreciate guided meditations.

I respect that some might share concerns that the headband could break the precept of noble silence or otherwise distract from the meditation process. From my perspective, I viewed the headband the same as the mat I sat on or clothes I wore. It was just part of the meditation environment. After the first few days, the results blurred together. Percentages of active or calm lost relevance to the process apart from casual observation.

The measures of calm and active also do not reflect what is happening within the mind. For example, nodding off to sleep during meditation registers as an active state. You can be in a calm state and gently thinking about the past or future rather than focusing on the breath. You can be diligently performing a Vipassana scan from head to toe and it may register as neutral state.

The levels are also relative to the initial calibration performed each time you start a meditation session. If you are active at the time of calibration, the levels during meditation tend to be recorded as calmer. It is important to start the meditation session when the calibration starts so the session reflects your current state.

For these reasons, it may not be appropriate to say from the results “I am active” or “I am calm”. More accurate would be to say, “Muse indicates a calm or active state”. You can then determine what meaning if any those results have for you.

Like most feedback, Muse results should be observed without placing judgement.

Another aspect of using the Muse was that it needs the phone app. This proved problematic as it meant I would have my phone with me the entire time. While I could stay away from the apps, I admit to clicking on a few notifications that came up early on. I was also not confident that I had left everything in order back home before I left. I initially checked emails to see if anything had come up. This turned out to be unnecessary.

I turned off all notifications a day or so into the process. Since leaving the course, I do not expect that I will turn notifications back on. I opt instead for scheduled check-ins through the day for relevant social sites and emails.

The lead-up and preparation

There were things I had to consider that would not have been required had I attended a formal course.

Coaches and conversations

I reached out to a couple of mindfulness coaches as I planned the retreat. I also had a chat with a couple of friends who had been on the 10-day course. I could only get so much from blogs and books, and I acknowledged that I did not know what I did not know.

I had heard of people experiencing unexpected and confronting emotions through the process. One of the coaches mentioned that he was interested to hear what “came up” for me. I had been streaming the Alien movie series with my kid through December in our weekly Zoom catch-ups and immediately thought of an alien bursting out of my chest during a morning meditation session. Another of my friends who had done the course mentioned I was “brave” for attempting to do it on my own. Brave seemed a strong word for sitting in a room by myself for a few days. I questioned what I was getting myself into.

Reflecting from the other side of the process, I now understand what they meant. There is a smorgasbord of distractions available in daily life. These occupy the mind away from otherwise unwanted thoughts. Remove the distractions and the mind has nowhere else to go but into itself. I am grateful for the conversations in that they helped me to acknowledge that what I was experiencing was normal, even though it did not diminish the intensity of the experience.

This is likely also why the formal course advises against participating if there are underlying mental health issues or chemical addictions. Meditation can be a powerful tool as part of other support including professional help and accountability communities and programs. I would not propose someone with significant pre-existing conditions attempt a 10-day silent retreat on their own without on-site support as their first option.

Books

Many people share the benefit of heading into a 10-day program not knowing what to expect. There is an element of trusting the process and experiencing it as it comes up. As I was preparing my own program, I was recommended William Hart’s The Art of Living which I listened to as an audiobook. I also listened to the personal account of Robert Crayola’s Vipassana Meditation audiobook. These helped me understand and plan the process without taking away from the experience. Other books that have informed my perspective include How to Practice by the Dalai Lama and Peace is Every Step by Thic Nhatr Hanh.

Food

For my height and weight, meditation consumes around 900 calories a day. My diet over the 10 days equalled roughly that amount. Breakfast consisted of three tablespoons of oats and a couple of slices of canned fruit. For lunch, I had a sealed packet of vegetarian curry. Evening tea was an apple, a carrot, and some watermelon while it lasted for the first few days. I also had a handful of plain almonds with the evening lesson. I included coffee in the morning and at lunch, and a tea in the evening.

I was surprisingly not hungry through the process. I looked forward to each meal for the experience of eating rather than a desire to fill my stomach. I often find I am “mind hungry” more than “stomach hungry”. I eat to consume attention rather than calories.

I was also keen for the opportunity of a physical detox. I gained three kilos eating and drinking my way through December, for which I have zero regrets. I left to start the process on Boxing Day Saturday. I expect I was still digesting Christmas lunch well into Tuesday. I do acknowledge though that physical and mental clarity go hand in hand. The ten days is a good head start on diet changes for the New Year.

As a side note, I also lost more than the three kilos through the process.

The location

I looked on Airbnb for a location that was far enough from home and the city, and where I would not know anyone. I also wanted to support a regional provider given the recent impacts on tourism from the pandemic. Finally, I was after space to avoid any possible distractions.

I searched in Queensland from Goondiwindi to North Burnett. I decided on a perfect farm stay in North Burnett about four and a half hours drive from home. The drive also allowed me to prepare heading into the process and returning home.

The farm stay was on top of a hill and provided 360-degree views of trees, hills, and grassland. Cows roamed outside the front gate. Crows, galahs, magpies, and black and white cockatoos flew by the windows and provided a soundscape to accompany the wind gently rattling the panes. I regularly escorted green frogs out of the bathroom and learned to keep the toilet lid closed to avoid breaking the no killing rule with a flush in the middle of the night. The only reminder of a functioning society was the occasional car passing along the single stretch of road 300 meters away.

Family

Even though I travel frequently for work, there is no convenient time to be away for ten days. My time fell over New Years and my stepson’s 16th birthday. I prepared flowers for New Years and a pre-recorded video message for the birthday, but I still missed family over the holidays. I am grateful for their support through the process.

Precepts

There are certain precepts to be held during a 10-day Vipassana course. These include:

- to abstain from killing any being;

- to abstain from stealing;

- to abstain from all sexual activity;

- to abstain from telling lies;

- to abstain from all intoxicants.

The requirements also include following a noble silence, which includes no talking, or digital or written forms. These were all straight-forward. There was a tense moment involving a two-inch wasp that found its way into the meditation room and was hanging out on the window screen. I admit to contemplating options of bug spray or a rolled-up magazine before opting for a glass jar catch-and-release method.

Schedule

The daily schedule went as follows:

- 4:00am: Wake up

- 4:30am – 6:30am: Meditate

- 6:30am – 8:00am: Breakfast

- 8:00am – 11:00am: Meditate

- 11:00am – 1:00pm: Lunch and rest

- 1:00pm – 5:00pm: Meditate

- 5:00pm – 6:00pm: Tea break

- 6:00pm – 7:00pm: Meditate

- 7:00pm – 8:15pm: Discourse

- 8:15pm – 9:00pm: Meditate

I have been an early riser since the US Navy, so the 4:00am wake up was familiar territory. Each day was the same, and different. Some sessions seemed unusually long, other days passed quickly. Far from ‘relaxing’, the meditation sections required focus. I took advantage of the break times to catch quick naps. Even still, I caught myself nodding off in the evening sessions and would occasionally need to replay the evening instruction over meals the next day.

A challenge and benefit of the process is that you are the facilitator, the participant, and the assessor of your journey. You are your own reference point, apart from the anchor of the evening discourse. Thankfully, the evening discourse is appropriate for each day. It is as though the instructor knows what you have been going through, explaining how to interpret your experience and adding mental models to help with the following day.

Meditation reflections

What follows are reflections from each day of the process.

Day 1 – Be aware of the breath and know thyself

There was no guidance heading into Day 1. Just a schedule of meditation times and a need to focus on the breath. While I had done 4-hour stints in the past, this would be the longest I had meditated in a day. I was nervous but encouraged by the novelty, curious as to whether I could do it, and bound by the fact I had made the commitment.

As the tedium set in, I started to develop mind tricks to focus my attention. While I had read that visualising on a word or religious construct was discouraged, I began to keep focus by saying “This breath”. Breath in – “This”. Breath out – “Breath”. In – ‘This”. Out – “Breath”. There was a chair in front of me and I also began to play in my mind about the form of the chair – the structure and shape -, the function of the chair – for sitting or standing -, and its aesthetics – the grain of the wood and shape of the bolts.

I Initially thought how clever I was to easily calm the mind. That evening’s recorded instruction admonished my inventiveness as though it knew what I had been up to. The speaker noted that using visualisation of shape, word, or form does indeed help calm and focus the mind. It is a common practice with spirituality, focusing on a deity, scripture, or a single word or value.

But the aim of the exercise is not to calm the mind but to change the behaviour pattern of the mind. Visualisation takes the focus off the breath and does not build up the necessary skills. It is like listening to music while working out or attaching confidence to what you are wearing. It can help in the moment but leaves you at risk if those conditions are not present.

I am also physically inflexible. Me doing yoga reminds me of cheap toy action figures I had as a kid that only bent at one point at the hip, and even at that it was only 45 degrees. Sitting cross-legged for more than five minutes felt like torture. Thankfully the evening instructor acknowledged this and said fidgeting in the first few days was understandable. I took him up on the offer, even as I worked to view the pain as a process. Rather than an attachment to self that “my knee hurts”, the pain in the knee is to be observed as a process happening in the body.

The aim, we are told, is to ‘know thyself’ through observing the breath. When the mind experiences a good sensation, it wants to repeat the experience producing craving and clinging. We then have the likelihood of attaching our identity to that sensation. When the mind experiences a bad sensation, it wants to avert from the experience and turns to agitation. In this way the mind is ignorant, moving from sensation to sensation without awareness, from aversion to craving. Our thoughts, emotions, and actions follow in ‘mindless’ automation.

Focusing on the breath helps to observe and therefore inform the mind, reducing ignorance and increasing knowledge.

Day 2 –Train the mind, do the work

Day 2 maintained a sense of novelty. I was sore, but also a bit more flexible, able to maintain a cross-legged position for up to 20 minutes. I also had what I can best describe as a ‘sense’, clear memories of my childhood I had not thought about for decades. What followed was a period of interactive and lucid scenes, borrowing from the past and applying to the present.

The experience seemed to happen in an instant, but around 2 hours had passed. I thought perhaps I nodded off, but Muse did not show the type of pattern I usually see when I fall asleep during meditation. I am not prone to fascinations or visions and hesitate to document this here at risk of it being misinterpreted as something it is not, either as promoting a spiritual vision or a poor reflection on my mental state.

In reading the accounts of others however, such experiences are not uncommon. I chalk the experience up to a change in diet, new sleep patterns, a novel environment, and quietening external noise through meditation. Perhaps it was a lucid dream state, perhaps a hiccup of the subconscious, perhaps something else. I capture it simply as one of many outputs from the experiment in case others have a similar experience, or if others do not share the experience as a point of comparison.

The discussion that evening describes the mind as wild and agitated, like a monkey grasping one branch after the other or a rampaging elephant going wildly in one direction or another. The purpose of meditation is to turn the wild mind into a service to society.

No one can harm us more than our own wild mind and no one can help us more than our trained mind.

Like training an elephant, it takes patience, persistence, and experience. Also like an elephant, we do not judge it when it rampages. That is just what elephants do. We continue to gently guide it on the path.

While spiritual doctrines are not emphasised in the practice, there is a notion of good and evil. Any action that harms another being is a sinful action. Any action that helps another being is a wholesome action. Sinful and wholesome actions start in the mind. You are the first victim of your anger.

The next day we are told to be more subtle in the practice, and focus specifically on areas of the breath, to feel one thing, to focus on one reality.

Day 3 – Learning through experience

Only two days in and I wake on Day 3 thinking I could just stop now. But heading into the mediation I am struck with gratitude at the opportunity and I continue. Still, as the day passes without note, the impatience comes in waves. Even as I observe the breath, I observe the impatience and let it go. I find this prepares me for what is to come in Day 4.

The talk that evening discusses three ways in which we learn about reality: through hearing, through understanding, and through experiencing. We learn in part through hearing, and some might go off and feel they have the picture. You might read this post and feel you can discuss meditation. We learn more through understanding. You might research further, read other blogs on Vipassana, and feel you can teach others about meditation. But reality is always distorted until we learn through experience and speak from the reality of our experience.

It is only through experience that we truly learn.

The past three days have been a foundation. The process of Vipassana begins tomorrow, expanding the focus from the breath to the body.

Day 4 – a wild ride

Day 4 was a wild ride. Shortly after starting the mid-morning session, a gamut of frustration, anger, desire, and challenges came to mind. More than just fleeting thoughts, my mind was consumed with mental narratives, arguments, visuals, fights, and debates. I worked to focus on the breath, but the thoughts were all consuming. The more I fought, the stronger and more entrenched the thoughts came. I caught myself holding my breath, having shallow breath, tense, and with a tight chest. It was tempting to get up, walk around, process, and otherwise find distractions. But I sat in silence.

Growing up in American Pentecostal churches, I recall speakers sharing similar tales of wrestling through prayer and fasting experiences. Except in their case, they attributed the thoughts as an attack from demons and devils and looked to scripture, prayer, angels, and God to take the thoughts away. Similar experiences are shared across spiritual faiths and secular practices. The instruction that evening also referenced the potential for this condition.

My personal take from the experience is that the process over the four days removed noise and a sense of self that acted as a filter to cover over thoughts under the surface. Without distraction or counter-argument, the otherwise unwanted thoughts had free reign. This continued on-and-off for the better part of seven hours.

Over time, the thoughts did not go away, but the thoughts lost their connection with emotional and physical response or reaction. I would not refer to the thoughts as negative or undesirable. They became just thoughts without value or judgement. At some point, I was left with the breath. Except where previously there was discomfort, tedium, impatience, and boredom, there was now relief. Having just the breath without the clatter of emotionally-charged thoughts was like a literal breath of fresh air.

The evening discussion reviewed the process of Vipassana, moving from head to toe to focus the mind through identifying sensations in the body. The instructor explained four major segments of the mind: Consciousness – to recognise through the six senses; Perception – to recognise based on with experience, conditioning, and memories of the past and to give evaluation; Sensations – based on the perception to flow through the body; and Reaction – motivation and reaction of the mind and body.

Reaction gives fruit through repetition. Few repetitions are like a line in water, stronger repetition is like a line in the sand, and continuous repetition is like a line in rock.

Day 5: Dropping in

In the afternoon I had a new experience. First, I recalled that I could not point to a specific time from my previous meditation sessions where there was discomfort. And yet I knew that I had at some point experienced discomfort. The discomfort was temporary and lost its meaning. This helped put the current discomfort in perspective.

In the afternoon I found I could ‘drop in’ and ‘drop out’ of meditation with ease. When I ‘dropped in’, it felt like I was in the zone and that time both stood still and sped up. When I ‘dropped out’, it was as if I was observing myself meditating in the third person. This kept up through the four-hour afternoon session. There were other times in the session where the meditation was not so easy and I did not attempt to hang on to the sensation, but I appreciated the experience.

The evening session spoke of moving to the deeper areas of the mind to understand the clinging and aversion, exposing the blind habit patterns. The aim is to ‘know’ beyond the intellectual level and learn at the experiential level to break the barrier. This is to avoid the sleeping impurities and volcanoes that may lay dormant, training the deeper level of mind to not react.

Through meditation, we can accept the reality of the misery, not react, and just observe. This stops the process by which we multiply any physical pain we experience with mental pain which comes from craving and aversion.

Day 6 – Practical application

Day 6 was a continued narrative of the previous day. My mind continued to gravitate towards various scenarios, personal relationships, and work challenges. In some cases, I observe the relationship similar to how I might observe my breath; objectively, pragmatically, and without judgement. In doing so, I understand my emotions and my role in the context which helps consider a course of action. I acknowledge that these scenarios and even the work itself can be a form of addiction.

The discussion in the evening highlighted the mind’s addiction to craving. The craving is not for the object, but for the sensation brought about by the object. The instructor notes for example that the addiction is not necessarily for the alcohol or drugs, but to the sensation they bring (acknowledging the physiological realities of chemicals on the brain). Once the sensation is obtained, the craving can become stale, and a new craving emerges or the craving escalates. The form of sensation can be defined by your personality, following a habit pattern of the mind. Meditation is one approach to support overcoming aversion through the repetition of not reacting.

Five barriers to this process include the two main ones identified of craving and aversion, as well as laziness which leads to drowsiness to avoid the practice, agitation resulting in distraction from the practice, and doubt.

Pressing pause

I pressed pause on the 10-day practice after Day 6. This was not without some internal debate. I remained curious as to what further changes or insights I might experience from an additional 40 hours of work. The instruction also gave warning of a potentially negative impact from leaving the process early.

I had gained much from the process and have no doubt there is more to learn. But the temptation to take advantage of the silence and the idyllic setting was strong. I wanted to capture my thoughts, step back, reflect, relax, and prepare. I spent the next few days continuing morning meditations, writing, and reflecting while staying in the silence. I was also able to prepare for the year ahead, as I knew I would be hitting the ground running when I returned and was also keen to spend time with family without rushing.

I considered whether this was simply a craving of the mind. Perhaps I missed out on a great epiphany from not continuing the practice over the final days. If I had been in a structured course, I would have likely continued due to lack of any other option. But I am grateful for the clarity and time I had.

Reflection, practice, and where to from here

The day I came out of the retreat was the day the US capital was being stormed and the media cycle was in an understandable frenzy. Rather than either retreating back into silence or embracing seeming chaos, the meditation practice encourages leaning into reality to fully understand what is happening and our position. The situation in the US is saddening. It is also motivating for the the work I am involved with helping communities understand differences to better facilitate sustainable regional change and transition.

I took away two main reflections from the meditation experience. The first is compassion. A lesson from the past year is that everyone is on their own journey. I believe the main challenge facing society is the notion of ‘us versus them’. We can have an aversion to ‘the other’ that is not like us or represents a part of us we do not wish to acknowledge. We can also have an attraction to those who are like us, who reinforce the view we want the world to see. Compassion and understanding breaks down these differences. But before we have compassion for others, it usually starts with understanding ourselves. Meditation assist with this practice.

The second reflection is gratitude. First, I am grateful for the lessons from the experience I had over the ten days. I am grateful for those who have gone before me to build up the collective wisdom from which I can learn. I am grateful for those who have supported and contributed to my learning over the past year and those close to me who journey with me in life. And I am grateful for the opportunity to live out my vocation in my current field of practice. That gratitude is a strong motivator to give back for what I have been given.

As to the practice of meditation, I come away with a tool for clarity and focus. Meditation is not a cure-all. It should be used in combination with other approaches to overall wellness. Meditation is also not just doing time. It takes work and focus. If you go to a gym for a five-minute stroll on the treadmill before pounding the big bacon breakfast at the local diner, you will not expect to be physically fit. Similarly, if you only go through the motions of meditating and do not put the effort in to control the mind, you should not expect to see results.

There is value in a regular practice of silent meditation. Like a gym, meditation is training for the muscle of the mind. Meditation is not just relegated to the yoga mat and secluded house on a hill, however. We have access to the breath wherever we are. Returning the breath ‘in the moment’ provides a grounding, an ability to distinguish between thought and response, and to make decisions accordingly.

The experience also provided a level of discipline. Doing nothing can be one of the hardest things we do. My intermittent daily meditation practice previously ranged from 10 to 30 minutes. I now know I can sit for ten hours a day over several days. This has greatly diminished the fear from the boredom.

So where to from here? Over the next month I am engaging a mindfulness and performance coach to embed the practice. I will also be continuing the morning practice of meditation to coincide with a fitness routine that fell by the wayside towards the end of the year. I am also tweaking my productivity stack of OneNote, Trello, and time tracking (aTimeLogger for the iPhone) which has served me well in the past.

If you have read this far, thank you for going on the journey with me. I welcome any insights from your own experience, and happy to share anything further for those planning a similar process.