Speeding tickets and Kohlberg’s model of ethical decision making

I received some feedback on my driving the other night. I was driving home from the train station on a familiar stretch of road when I saw these two men energetically waving from the side of the road to get my attention. They looked friendly so I pulled over to see what they had to say.

It turns out they simply wanted to give me a pop quiz on the topic of the local speed limit. I am always up for a challenge, so I gave them my best response to their question. They smiled knowingly, borrowed my driver’s licence, and went back to their car to confirm that I had the right answer. I am not sure why, as it was an open book test, with the speed limit clearly posted on the sign I passed a few meters back.

When the man returned, he told me I had indeed given the correct response. As a reward, he gave me the opportunity to donate $146 to the local infrastructure. I thought this very gracious of him, and drove away thinking how fortunate I was to be selected for the test.

As I made my way home, I considered how the events that had just unfolded were a result of a series of decisions made through the course of my life based on a framework of beliefs and decision-making processes.

Kohlberg’s stages of moral development

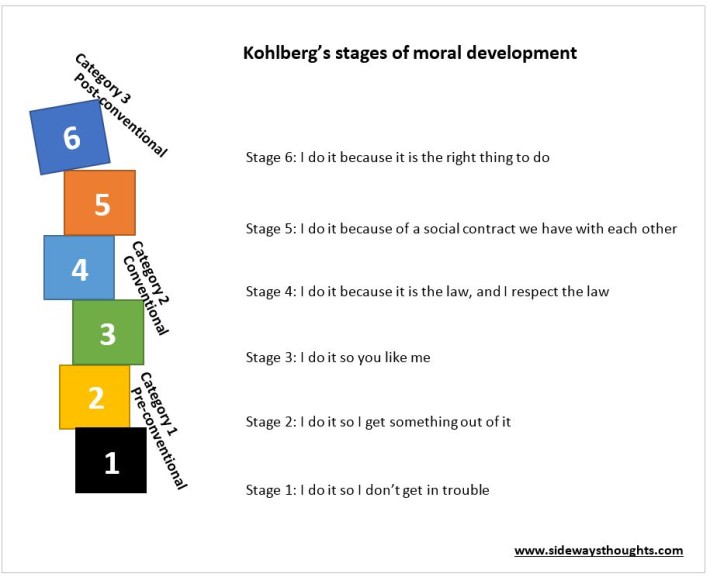

The speeding ticket scenario is often used to highlight Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. The model was developed by Lawrence Kohlberg in the 50’s and 60’s and outlines six progressive developmental stages for moral decision making.

The six stages are grouped into three categories (two stages each), with each category defined by how a person makes decisions in society.

The first category is called pre-conventional. The person in this category operates from a perspective focused on themselves, largely unaware or uncaring about the society in which they live. This category is often associated with children at lower levels of maturity.

The middle stage is called conventional, with the person acknowledging the society in which they live. People move into this category as they move past adolescence and interact more with those around them.

In the later post-conventional stages, the person remains aware of the surrounding society but may make decisions based on a higher moral reasoning that may transcend the rules created in that society.

These three categories contain the six stages of Kohlberg’s moral reasoning, outlined below:

Category One: Pre-conventional

Stage 1: Obedience and Punishment (“I do things so I don’t get in trouble”)

Those in the first stage are like a child, basing their decisions on compliance to an authority and the risk of negative consequences for failing to obey. A negative consequence means the person is wrong, and avoiding a negative consequence, or punishment, means the person is right. They do not consider the impact on others, only the outcomes based on the negative impact on themselves.

Stage 2: Individualism and Exchange (“I do things so I get something out of it”)

A stage two perspective is still childlike, but situations are no longer black and white, right and wrong. There can be varying degrees of loss or gain; relative outcomes based on the value a person receives from the activity. The person does not yet consider the impact on others, but only sees decisions in relative befit to themselves.

Category Two: Conventional

Stage 3: Good Interpersonal Relationships (“I do things so you like me”)

In stage three, the person begins to consider someone other than themselves. They think about their immediate social circles, be it their family or friends, when they make decisions. The person starts considering their actions based on the impact it might have to those they care about or those they have relationships with.

Stage 4: Maintaining the Social Order (“I do it because it is the law, and I respect the law”)

The person in stage four extends their thoughts of others beyond their immediate circle of family and friends. They make decisions out of respect for the social order and the law that maintains that social order. They are not primarily concerned with fear of breaking the law, but rather acknowledge the intent of the law for the greater good.

Category Three: Post-conventional

Stage 5: Social Contract and Individual Rights (“I do it because of a social contract we have with each other”)

The stage five individual extends beyond the law for law’s sake and makes decisions based on what makes for a good society, at times irrespective of the law. The person acknowledges that decisions made for the greater good can at times violate the letter of the law. Of primary concern in their decision-making are concepts such as “morality”, “rights” and democratic processes.

Stage 6: Universal Principles (“I do it because it is the right thing to do”)

Stage 5 decisions may be right for the majority, but they may not be just. As such, the stage 6 individual is primarily concerned with justice. Whereas the person at stage 5 may be more focused on establishing status quo, the person at stage 6 would possibly consider civil unrest and revolution to effect a greater change for long-term social justice and sustainability.

Testing the model with speeding tickets and polar bears

Coming back to my speeding ticket experience, it is clear I was operating at Stage 1 as I drove home. While only 12 km over the limit, my behaviour reflected a belief that I would not get caught.

Compliance-based punitive systems like traffic fines are based on the understanding that there are many who apply this same school of thought. Yet we also have other mechanisms in place in the hopes that people will evolve to higher orders of moral development. For example, insurance companies offer discounts for those with a clean record to encourage those who may want to get something out of their driving behaviour (stage 2). Marketing messages promote safe driving to encourage people to think beyond their immediate selfish concerns, respecting the social order and maintaining good interpersonal relationships (stages 3 and 4).

It is rare, however, that people are encouraged to comply simply because it is the right thing to do. I encountered Kohllberg’s model in action when I worked at the Environmental Protection Agency promoting the agency’s voluntary environmental efficiency program to businesses.

It was 2006 and environmental sustainability was a hot topic. Ex-US Vice President Al Gore was doing the rounds with his Inconvenient Truth and everyone wanted to hear about the “business case for sustainability”.

I quickly discovered that melting ice caps and stranded polar bears held little relevancy to the small business operator. Businesses did not engage with a sustainability sermon based on what was the right thing to do or some sort of collective social contract. What was effective was telling businesses they would be left behind, that they would attract better employees, that customers and government contracts were looking for green companies, that environmental practices generally made good business sense, and that there was a potential rebate associated with the program.

I realised that some may talk about doing the right thing in business, but actual decisions tend to be made based on a desire to stay out of compliance violation (stage 1), for increased profit (stage 2), or better brand positioning (stage 3). Leaders may perhaps extend their decisions towards the benefit of their industry or local community (stage 4). Our profit-driven mandate is not set up to promote decisions based on what is best for society in general (stage 5) or for broad justice-based universal principles (stage 6).

Moving on up

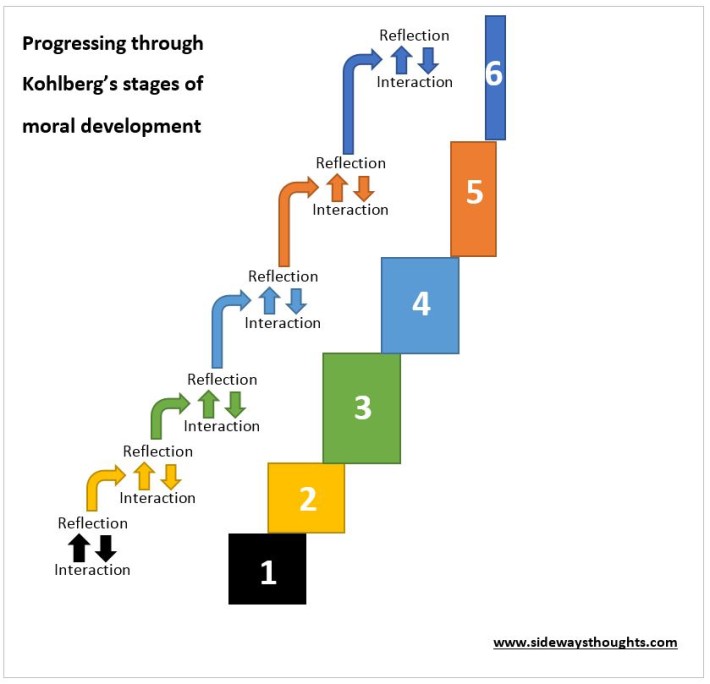

So how is business behaviour related to my speeding ticket? Making the connection starts with an understanding of the way we progress through the stages of moral development. As we mature, we move through each stage based on information and feedback we receive through our interactions with each other and our ability to reflect on that information. Every interaction we have with each other either justifies our current stage or challenges us to consider a new stage of moral development.

If this is true, then what types of interactions do we have to reflect on? Do our interactions promote the early stages of self-interest, or do they support a consideration for a greater social good?

This question was on my mind when I recently opened the Australian Financial Review. A story on page 19 noted a European Commission proposal to have listed companies justify large gaps between executive pay and that of the average worker in the same company.

The article highlighted examples of inequality between the chief executives and the average worker. Gaps of chief executives of financial institutions are at 181 times for Barclays and 125 times for Lloyds, and pay for US-based chief executives for Walt Disney are at 653 times and Coca Cola at 427 times more than the median pay of their employees. The Financial Times and Stock Exchange (FTSE) top 100 chief executives total pay in 2013 was 120 times the average earnings of their employees, up from 47 times in 1998. Director pay in France rose by 94 per cent between 2006 and 2012, even though average share price fell by a third.

Management guru Peter Drucker is quoted as recommending a maximum ratio of 25 to 1 between executive pay and the average employee pay. This recommendation falls well below the actual average pay gap of 204 times according to Bloomberg.

In response to the European Commission’s proposal for greater governance around pay inequality, the UK Institute of Directors asked: “Have shareholders asked for data on pay ratios? If not, then it’s not clear why the European Union should legislate.” This leaves me with questions of my own. Do we really operate in such a closed system that only shareholders with a vested interest have the right to raise the question about inequality?

Speeding to higher moral reasoning

How can we hope to address global inequality if we cannot get it right in our own corporations? Yet I turn my questioning back to myself and ask whether I have a hope of making a difference for the greater good if I cannot get the local traffic laws right.

This reasoning was echoed by Martin Luther King Jr. when he said:

“Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. This is the interrelated structure of reality.”

This quote was highlighted by a recent Doctorate that explored what people are looking for in their spirituality. The primary theme from over 470 interviewees was that “I want to be a better person, and I want you to be a better person”.

The Doctorate findings support Kohlberg’s notion that we search for ways to progress through stages of moral development through our interactions. Our experiences in the amoral, self-interested business sector do not tend to cause us to reflect on the value of thinking beyond ourselves towards the greater good.

Applying Kohlberg’s model, two things need to happen if we are to see the world beyond ourselves and consider how we might leave this world in a better place than when we arrived.

- Seek out different interactions

We must seek out interactions that cause us to reflect in a way that is different than the dominant thought. Corporations are a poor source of a moral compass. We need to expose ourselves to what philosophers refer to as “the other”; concepts, people and situations that are different to the status quo and that challenge convention of self-interest. - Be the change

Executive pay inequality did not get my speeding ticket, I did. If I am unable to change my own behaviour for the greater good, then how can I expect change to happen in others? As Gandhi is quoted as saying, “Be the change you wish to see in the world”.

I am grateful for those gentlemen on the side of the road that night, in that our interaction prompted my reflection on my moral development.

I am also grateful to you for interacting with my reflections. If these thoughts caused you to reflect on your own stage of moral development or you feel others may benefit from similar interactions, please feel free to share using the links below.

“While only 12 km over the limit, my behaviour reflected a belief that I would not get caught.”

This would be an interesting sentence to explore further, in particular: “…only 12 km over the limit.” I think you could learn much from this very instructive video. 😛

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZStS_7SGg5o