Finding your organisational fit based on Holland’s vocational personality type

We spend much of our working lives finding our ‘fit’ in organisations. Those who feel misaligned can speak of feeling like a ‘square peg in a round hole’ or, alternatively, that they are in a role that ‘fits like a glove’. What do we mean by ‘fit’ and does it make us more satisfied in our role?

Introduction to the concept of fit

My interest in fit started back in 2009 when I reviewed how our roles connect organisations with the values, interests and strengths of the people in them. It made sense to create roles that aligned goals and interests of each party, supported by a concern by each for the other’s well-being.

Fit is seen to be so critical that it has spawned a myriad of tests such as Strong’s Skills Confidence Inventory, the Minnesota Importance Questionnaire, the Adult Career Concerns Inventory, and the Career Beliefs Inventory. One of the more popular approaches is John Holland’s self-directed test based on his Vocational Personality Theory.

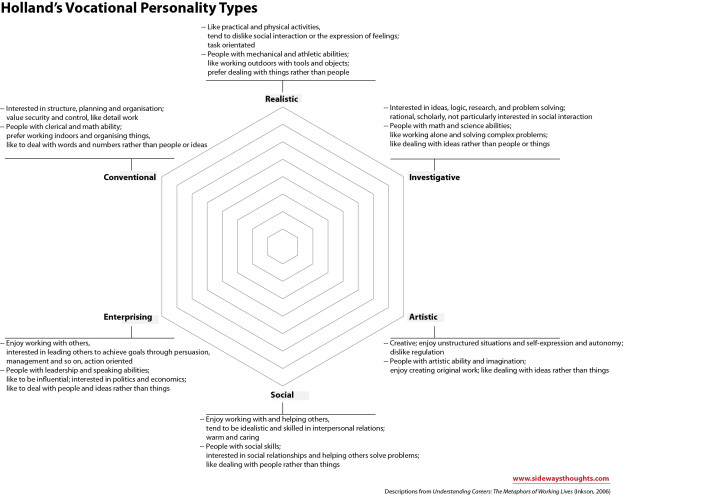

Holland proposes that we are made up of a combination of six vocational personality types. These six descriptors form a hexagon in which there is typically greater alignment between adjacent types and less alignment in opposite types. For example, people could tend to be both conventional and realistic, but it is unlikely they would be both conventional and artistic.

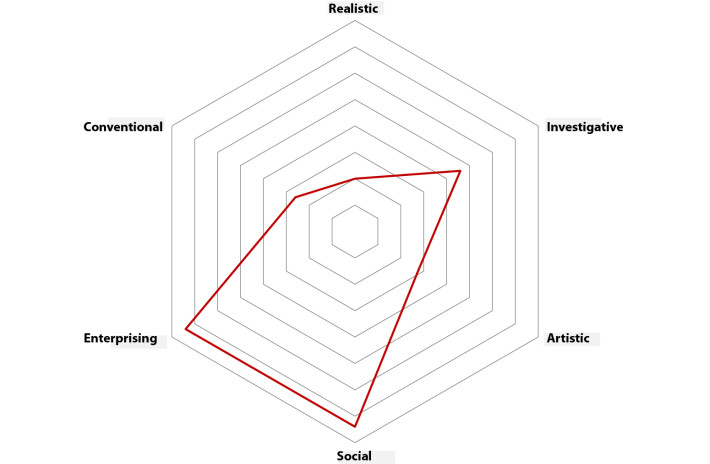

If you are keen to find your type, you can take the test at Self Directed Search for US$4.95. I gave it a try and my results are below. Those who know me would not be surprised by my types of social, enterprising and investigative.

The test is very simplistic, in that it asks you if you prefer certain types of roles and then presents back how much you prefer certain types of roles. This is like saying I like chocolate and then being surprised when I buy chocolate.

The value in the process is articulating not only what you prefer, but also what you don’t prefer. This forms part of your ‘shape’, to which you are then encouraged to find positions and occupations that have a similar shape to define your fit.

But does it work?

All this sounds good in theory. However, research has shown mixed support for having a good fit and our overall satisfaction.

Obtaining an ideal fit, as well as a correspondingly lack of fit, has been found to be a weak predictor of job satisfaction. Aligning your codes with a certain profession will not necessarily make you satisfied, and just because you are not in an ideal situation does not mean you cannot be satisfied in your role. Part of this determination is based on whether you view traits you are weak in with indifference, or whether you treat them with outright aversion.

The test is also subject to cultural differences. A 1996 study noted that 15 of 18 non-US countries showed a poor statistical fit with the model. There are others who find some correlation, such as one study of 156 Greek university students, and another with 376 South Korean university students.

One of the reasons why the test is not directly correlated with satisfaction in a profession may be due to a stronger correlation expected with a role within a given profession. Others have noted that adaptability is more important than fit and rational decision making, which supports findings from my recent post on characteristics of adaptability and self-belief for those who take action in their careers.

How to use fit

So getting the right fit based solely on your interests may not result in satisfaction, but it can help predict preference and what a person will stick with. For example, Holland’s scale has been used to successfully predict medical students’ career aspirations and their potential to maintain or abandon those aspirations.

The notion of fit goes beyond our inclinations and interests, however. Rather than viewing fit based on function and activity, perhaps the notion of fit aligns more with characteristics such as values and culture. We can see this when we hear people refer to a “values disconnect” or “cultural misalignment”, one of the primary failures for mergers and acquisitions.

To use another metaphor, finding your fit does not mean you are “put into a box”. Rather, it can open you up to discovering how you can fit into most any situation.

For example, rather than needing to find a specific occupation that is designed for someone who prefers to be enterprising and social, I can ask how I can be enterprising and social in whatever career I am in. Being low in conventional and realistic, you would not expect to see me as an accountant, but I could work in an accountancy developing teams or growing the business through sales.

So long as there is a fit in values and culture, organisations should be able to handle most any personality. Indeed, getting the right mix of shapes could be seen as critical for innovation and growth.

I would be interested in your thoughts if you do decide to find your vocational personality type. If you find such actions fit with your type, I welcome your comments below.

Not sure I need to spend $4.95 to have someone tell me I’m realistic, investigative and artistic… but good article. 😉