Future-focused strategic planning: Corpus RIOS, Playing to Win, and Appreciative Inquiry

Strategy focuses our attention and energy towards a defined purpose. Our strategies both filter out activities we should not be doing as well as constrain us to things we should be doing.

Most business leaders would agree to the value of strategy. Yet strategic planning can be a challenge in a changing and uncertain environment. Where does planning fit when it feels like the context is shifting under the feet of the organisation? And when planning does happen, are there approaches to planning that are more effective than others?

To plan or not to plan

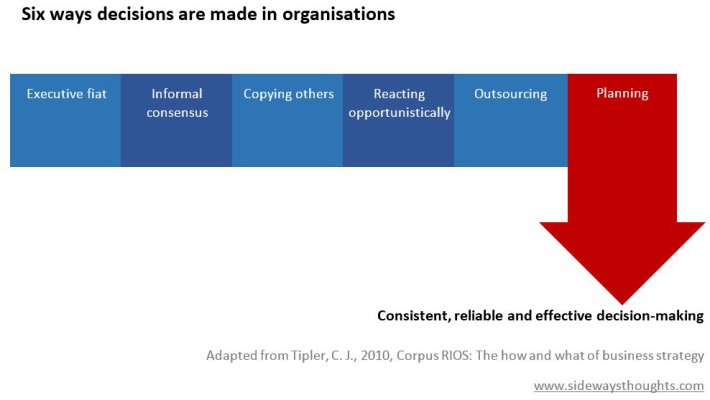

In his book Corpus RIOS: The how and why of business strategy, author Christopher Tipler takes issue with the way strategy is developed in his prescription for a revised strategic planning process:

Strategy development method 1: Strategy by Executive Fiat

What the CEO says, goes. This approach assumes the answers reside in the singular leader of the organisation. The strategy is enabled, and limited, by the knowledge, experience and vision of the CEO. This may work in some situations, but the CEO will eventually encounter situations he or she is not familiar with or make the wrong call. With a tenure of Australian CEOs at just over 4 years, basing strategy on the opinion of one individual is a risky proposition.

Strategy development method 2: Informal consensus

Similar to Method 1, the consensus approach relies on either the general agreement of the leadership team or the most popular opinion within the team. While this has the benefit of many voices, the strategic direction can be biased based on the functional composition and history of those in the team. The strategy may have an expansion focus if the dominant voice is from marketing or the focus may be on product development if the experience of the main players is more technical.

Strategy development method 3: Copying others

Often referred to as a “fast follower” approach, this method is driven by the ‘how’ rather than the ‘what’. Tipler notes that a copying strategy is based on an ability to execute rather than an ability to innovate. There does need to be a balance, however. A 2012 HBR article cites research that only 7% of innovators captured their market over time. The article notes the opportunity to become a learning organisation, asking not “Should I go first?” but rather “How do I accelerate the path to a breakthrough idea?”

Strategy development method 4: Reacting opportunistically

The opportunistic method is an easy-out in a rapidly changing environment. Tipler shares the idiom of “fire your arrow, and where it lands, call that the target”. Put plainly, a big move presents itself, you convince yourself it is central to your strategy, and after the event your organisational culture moves to rationalise and internalise the decision. This is the stuff of perfect hindsight case studies and management books for when it works, and chaos and ambiguity when it doesn’t.

Similar to method 3 above, there needs to be a balance with strategic planning and taking advantage of opportunities as they arise. An HBR interview with Don Sull, a teacher of strategy at MIT and London Business school, highlights challenges of businesses to remain competitive in a changing market. Sull proposes that “the key success in today’s volatile markets is strategic opportunism”.

Strategy development method 5: Outsourcing

I have been on both sides as an internal organisational leader developing strategy as well as an external management consultant assisting leaders to develop strategy. Based on both experiences I firmly agree with Tipler’s sentiment that outsourcing the definition of your strategy to an external agent is wholly inappropriate. Bringing in an external facilitator can be essential to drawing out the wisdom in the room, but abdicating leadership to a third-party will rarely end well.

Strategy development method 6: Planning

Which brings us to the final and only recommended way Tipler sees strategy being develop, and that is through a planning framework.

The problem with planning

The market knows the value of planning. Do a Google image search for strategic panning process and you will get enough flow charts and diagrams to last you a lifetime. There are a range of approaches to strategic planning that involve:

- Identity

A confirmation of the vision, purpose and/or values of the organisation. - Analysis

Often in the form of a SWOT (which looks at an organisations strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats), and/or PESTLE analysis (which looks at the political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental impacts on the organisation). - Framework

Apply a strategic framework to the analysis, such as Porter’s generic strategies, the Miles and Snow typology, the Boston Consulting Group growth matrix, and/or the General Electric–McKinsey nine-box matrix to determine where the organisation is positioned and where it should position itself. - Action

Define actions to support the strategies. - Measure

Defined how progress is measured against the strategy, often through key performance indicators (KPIs) and possible application of a balanced scorecard approach.

Roger L. Martin, who co-authored with Procter & Gamble CEO Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works, sharedthree comfort traps that contribute to what he says is the Big Lie of Strategic Planning:

- Comfort Trap 1: Mistaking strategy for planning

Planning itself is not strategy, although you can have a plan to execute your strategy. Planning is what happens between strategy and getting things done, but should not be mistaken for either. - Comfort Trap 2: Cost-based strategy

Revenue and costs are important, but not at the exclusion of understanding what has value to the customer. A strategy that looks only at budget lines items can be like the proverbial woodcutter who excels at chopping trees but ends up in the wrong forest. - Comfort Trap 3: Self-referencing strategy

The third trap is when strategy is defined exclusively by opportunities as they arise or the current resources within the organisation. Martin highlights a misuse of insights from popular management writers over the past few decades. One misuse is in using the concept of emerging strategy, popularised by Henry Mintzberg in his 1996 book The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning, as an excuse to not have strategy but rather go in whatever direction “emerges”. The other issue is not seeing new ideas as a result of exclusively focusing on the organisation’s core competencies based on a resource-based view, as outlined by Birger Wernerfelt in his 1984 article A Resource-based View of the Firm.

These challenges do not mean that leaders shouldn’t plan. Rather, both Martin and Tipler prescribe an approach to planning that avoids these common planning traps. Their recommendations focus on defining what winning looks like and how to realise that winning state. This shares the basic premise of an appreciative inquiry framework.

Planning to win

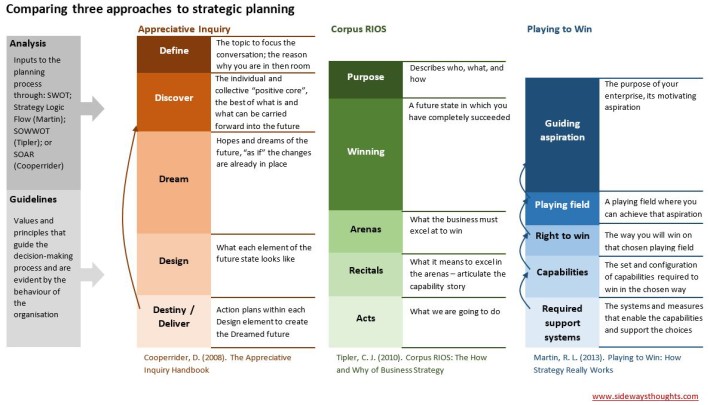

The outline below compares the approach of Martin’s Playing to Win approach and Tipler’s Corpus RIOS against the Appreciative Inquiry framework.The size of each stage is not indicative of the focus in the conversation, but simply an attempt to align where similar conversations happen in each process:

Supporting aspects – Analysis and Guidelines

Strategy does not happen in isolation of facts. There is typically an understanding of the context in which the organisation is working and what the organisation brings to the table. Facts can, however, overwhelm the planning process.

This can be addressed as Tipler recommends by asking “So what?” (SOWWOT). He highlights a challenge with traditional SWOT analysis producing a thousand interesting facts, of which only a few are insightful, and a smaller number that can be translated into powerful ideas meaningful to the business strategy. Martin shares this concern about an overwhelming amount of data in his proposal for a strategy logic flow to connect with what it means to win. Cooperrider raises concern about starting a process looking at the challenges, preferring to emphasis on strengths, opportunities, aspirations, and results (SOAR). The analysis needs to be relevant and build on the positive outcome, and is often revisited through the process to confirm and refine the inputs.

There is also the aspect of guidelines that support the decision-making process. Tipler prefers the concept of principles over values, highlighting that values are not part of the strategy conversation. Principles are the high-level rules that guide the behaviour of the organisation, whereas values can be considered the evidence of principled behaviour.

Stage 1: Purpose and identity

The approaches to strategy planning start with a confirmation of why the team is in the room. The purpose is the reason why the organisation, group or team exists, their reason for being. Tipler refers to the three-part test that asks who the customer will be, what customer needs will be met, and how these needs will be met. Martin starts the conversation with a future state by asking here what winning looks like as an aspiration. The conversation sets up the rest of the planning process to both empower and constrain available directions.

Appreciative Inquiry starts with a precursor step to Define the scope of the conversation, followed by a Discover conversation which can incorporate purpose as an outcome as the team explores their “positive core”.

It is best to identify and address early whether the purpose is not compelling to those in the room or if there are those who are not aligned with the purpose. To bring out the purpose, it can help to have a conversation about what the organisation is known for, what inspires the team about the organisation and their personal connection with the organisation. A well-developed purpose will motivate action and inspire creativity.

Stage 2: The positive future

Strategic planning can be considered from either pushing the organisation off from the current situation or pulling the organisation from the perspective of a positive future state. All the approaches mentioned propose the latter option.

A facilitated process called backcasting can help the team with the activity. Backcasting is a process where you take yourself to a point in the future and describe what you see, as compared to forecasting from where you sit in the present situation. When we forecast, we often do so firmly grounded in the constraints and challenges of the current situation. This can limit our thinking and inhibit innovation. Backcasting provides a means to think about a future without constraints, reflection on what could be.

The team also needs to determine how far to set the planning horizon, or how far in the future they look. There are lifecycles for products, technologies, organisations, markets and industries that can dramatically increase uncertainty when the horizon is set to far out. An operational team may focus on one to two years, whereas a board often starts at around five years.

Stage 3: Strategic areas

Once the team knows what the future could look like, the conversation moves to general ways in which they can get there. This is often achieved through a an approach where the team expands their thinking through brainstorming ways they can achieve the winning state and then consolidating the ideas into categories. These then become the arenas or fields in which the team will play to win. As Tipler notes, these are the areas in which the organisation or team must excel at in order to win. This starts to serve the purpose of strategy, which is to focus attention towards a desired outcome.

Stage 4: Meaning, narrative, and how

The next step is to determine what each category means. In describing the stage as recitals, Tipler notes that “A recital is an invitation; it invites you to act a certain way or in a certain direction and is therefore an immediate motivator.” For each arena, the recital describes what it means to excel at the arena. Martin speaks about identifying how to win in the areas where you will play. This is encompassed in the Appreciative Inquiry phase of Design, as the elements of the future state are expanded.

This stage brings life to the strategic areas, creating compelling reasons for each of the strategic categories. Anyone in the organisation should be able to connect to the meaning of the strategic area if they are working on an action out of the strategic plan.

Stage 5: Actions

The final stage is the actions and measures of the strategic plan. Tipler describes acts that need to happen in order to satisfy the recitals for each arena, typically set at 180 days or 24 months. Martin speaks of systems and measures, and Appreciative Inquiry provides space for detailed action plans.

The detail will depend on the resources available and the levels of leadership within the organisation. An executive leadership team of a large firm would like stay at high-level initiatives whereas an operational board for a snall not-for-profit may need to define specific action plans assigned to board members.

Strategic planning as though your (organisation’s) life depends on it

These are common frameworks for strategic planning, but each situation has a slightly different expression. All tap into the best parts of the organisation, connect with a compelling purpose, describe what winning looks like, and co-design how to get to that state through broad areas that are clearly understood and supported by practical action. The outcome is both energising and practical, building positive momentum.

The environments organisations operate in are competitive, constrained by scarce resources, and constantly changing. The need for leadership focus is as critical as ever. Simply having a strategic plan does not ensure success, but not having a plan at all could be seen as contributing to failure. Assuming the purpose of your organisation has value and the energy that is being invested into it is worthwhile, it would make sense to take some time to plan that investment.

I welcome your thoughts in the comments below based on your own experiences with planning for your team or organisation. Do you plan? If you do, do you use a framework? I also invite you to share using the social links below if there are others you feel could benefit from a strategic planning conversation.